The Imperfect Saxophone: Not Just a Clown’s Instrument

This exhibit examines America’s complex social and cultural relationship with the saxophone during a period known as the “saxophone craze.” Adolphe Sax’s most recognized instrument, the saxophone — invented and first produced between 1844 and 1845 — has had a very complex musical and social life. Originally developed to blend the distinct tonal qualities of the woodwind and brass instruments commonly used by Europe’s military bands, the saxophone’s startlingly unique sound made it difficult for professional musicians and composers of that time to embrace the instrument.

Despite Sax’s initial hopes that both symphonic orchestras and wind bands throughout Europe would eventually utilize the saxophone, the horn initially became an exotic novelty and was treated more like a musical clown than a fine-art instrument. America’s minstrel and vaudeville circuits were much less hesitant to accept Sax’s novel instrument in their performance routines. By the 1910s, the Five Musical Spillers, a vaudeville act, began incorporating saxophones into their performances with great success. They often used comedic humor and popular ragtime melodies to keep their audiences engaged with their performances.

The breakout saxophone ensemble during the 1910s was the Brown Brothers led by Tom Brown. Performing first as a trio on the minstrel circuit and later as a quintet and sextet on the vaudeville circuit, they were the first major saxophone ensemble to profit from making commercial audio recordings. By the early 1920s they were among the most popular and highest paid ensembles, earning nearly $1,000 per week. Up to 1914, the Brown Brothers wore military band uniforms. Once they began performing in the Broadway production Chin Chin, they instead began dressing as clowns. During this period, ensembles like the Brown Brothers helped popularize the instrument while embracing a musical clown mystique by performing popular ragtime works dressed as clowns. Despite appearing as a musical clowns, the repertoire that the Brown Brothers played required serious technical and musical skill.

Music instrument manufacturers of the time designed their saxophones around the needs of these top performers, but also capitalized on the growing popularity of the instrument among amateur musicians. These manufacturers also took the opportunity to improve Sax’s imperfect instrument, adding new keys and improving their methods of construction. As these innovative improvements were made to the horn’s original design and performers refined their ability to play this new family of music instruments, audiences quickly embraced the saxophone’s many unique musical qualities. This virtual exhibit, “The Imperfect Saxophone: Not Just a Clown’s Instrument,” exhibit highlights the saxophone’s imperfect musical beginnings and musicians like the Brown Brothers’ performances that made it a truly unique instrument.

America’s 18th Amendment, more commonly known as Prohibition, took effect in 1920, and quickly influenced all aspects of society, including music composition. However, songs and morality plays about the benefits of banning alcohol had existed in America long before the amendment’s ratification. The first temperance songbooks appeared before the Civil War as public interest in the prohibition and temperance movements gained momentum. During the mid-1860s urban neighborhoods blossomed with new arrivals from Europe, and new moral reform groups saw prohibition as their only remedy for controlling the country’s increased use of alcohol.

Musicians working in New York’s Tin Pan Alley and clearly on the other side of the Prohibition debate, frequently composed comical retorts to Prohibition that skewered America’s “wet” and “dry” movements. Tin Pan Alley was the epicenter of America’s popular music scene between the late-1880s and 1920s, and its most recognized composers – Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, Jerome Kern, and Cole Porter – served as musical foils to Prohibition.

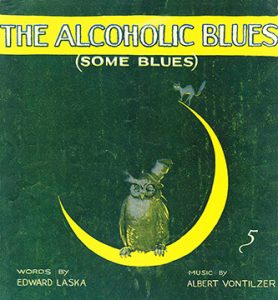

Unlike the Prohibition songsters that helped empower the suffrage and temperance movements, Tin Pan Alley songs swooned to the joy of alcohol. Songs like Jean Schwartz’s Sahara (We’ll Soon Be Dry like You), Albert von Tilzer’s I’ve got the Alcoholic Blues, and Irving Berlin’s I’ll See You in C-U-B-A expressed comical distain for prohibition’s benefits to society. Other songs, like Goodbye, Wild Women, Goodbye, lamented America’s expulsion from the garden of free-flowing alcohol.

The Sousa Archives’ virtual exhibit, Singing the Temperance Blues, illustrates the complex morass of America’s Prohibition movement during the 1920s through popular sheet music cover art, melodies and lyrics, and historical sound recordings from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

America’s Imaginations through Letritia Kandle and Eddie Alkire.

America’s fascination with Hawaiian culture reached its peak during the Great Depression. The country needed a temporary escape from the Depression’s daily uncertainties, and its people eagerly embraced Hawaiian music for their imaginary travels to exotic places. By this time, “slack-key” guitar had already become a part of mainstream American musical culture with its use of altered tunings and finger picking techniques first popularized in Hawaii by Portuguese sugar cane workers. Slack-key styles of the 1830s blended western-European performance techniques on a six-stringed instrument, called the guitarra portuguesa, and traditional Hawaiian melodies played on a four-stringed instrument originally called the ukeke, but today referred to as the ukulele.

Two of America’s leading performers, innovators, and educators of Hawaiian music in the 1930s and 40s were Letritia Kandle (1915-2010) and Eddie Alkire (1907-1981). Like many Americans, Kandle’s first encounter with the guitar was through Warner Baxter’s performance as the Cisco Kid in the film, In Old Arizona (1928). Although her early music experiences were with the Spanish style guitar, after watching performances during the Hawaiian exhibit at the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago, Letritia was inspired to take up the Hawaiian guitar. The following year she formed an all-women’s steel guitar ensemble called the Kohala Girls. In 1937, Paul Whiteman invited her to perform with his jazz band during his radio hour. She performed on an instrument of her own design; a four-neck electric guitar called the “Grand Letar.” By the early 1940s, Kandle had become a leading teacher of the steel guitar in downtown Chicago and eventually became the conductor of the Chicago Plectrophonic Orchestra, an ensemble made up of various string instruments including ukuleles and steel guitars.

Eddie Alkire began his career as an electrician in the coalmines of West Virginia. In the mid-1920s, he taught himself to play the steel guitar by enrolling in a series of correspondence courses. In 1929, he left electrical engineering to perform with the Oahu Serenaders, a group affiliated with Cleveland’s Oahu Publishing Company. As a member of this unique music ensemble, Alkire performed weekly on nationally broadcast radio shows on NBC and CBS. In 1934, he left the Oahu Publishing Company and formed his own music-publishing company and steel-guitar correspondence school. Five years later, he invented a new 10-string electric guitar, called the EHarp (pronounced Ay-Harp).

This online exhibit “America’s Hawaiian Imaginations through Letritia Kandle and Eddie Alkire” examines the innovative teaching methods and new guitar technologies developed by Letritia Kandle and Eddie Alkire during the 1930s and 1940s.

Sousa Archives’ World War I Sheet Music Resource

Sousa Archives’ World War I Sheet Music Resource

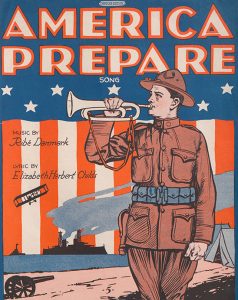

Myers Sheet Music Online Collection

Throughout 2014 the staff of the Sousa Archives and Center for American Music worked with William Brooks, Professor of Music at the University of York, and the University of Illinois Library’s Digital Content Creation, Content Access Management and Metadata units to digitize the WWI sheet music contained in our James Edward Myers Sheet Music Collection. World War I is considered by many music scholars to be the most musical war in America’s history. The music from this time was created by all sorts of Americans: professional songwriters, acclaimed composers, church musicians, well- and little-known performers, and uncounted singing teachers, small-town bandmasters, and amateurs. Their melodies and lyrics reflected various public perceptions of and responses to America’s evolving relationship with this War, and much of this music resonated local themes that were specific to communities, ethnic groups, or organizations.

The WWI music contained in the Myers Collection documents not only what was produced by Midwestern publishers but also offers a compelling cross-section of popular musical practices and tastes across the Midwest between 1914 and 1918. The music, lyrics, and graphic art illustrations contained in this new online resource are intended to provide insights into American life during and after the War for students, teachers, and scholars interested in learning more about Midwestern perceptions of this military conflict. For further information on the James Edward Myers Sheet Music Collection please call 217-244-9309 or send an email to sousa@illinois.edu.

Reaching Beyond the Walls of the Concert Hall: A Live Improvisation Concert Featuring the Sal-Mar Construction

Reaching Beyond the Walls of the Concert Hall: A Live Improvisation Concert Featuring the Sal-Mar Construction

2012 On-Line Concert

This special telematic music performance on October 26, 2012 brought together University faculty, musicians, archivists, and special collections curators as well as performing musicians from around the country to collaboratively create an innovative concert experience that takes the live performance beyond the walls of the traditional concert hall. This special online concert removed both time and physical barriers to connect musicians through the use of high-speed broadband connections to produce a real-time streamed audio-visual performance. This concert was created to celebrate the Morrill Act’s continuing impact on liberal and mechanical arts education in colleges and universities around the world. Performers included Ken Beck (Sal-Mar), Greg Danner (Sal-Mar), Erik Lund (trombone), Dorothy Martirano (violin), Barry Morse (theremin), Jason Finkelman (African drums and electronic music), Yu-Chen Wang (gu-zheng), Eduardo Herrera (guitar), Nathaniel Ruiz (clarinet), Chris Vaisvil (electric guitar), and Drew Whiting (alto saxophone).

A Live Improvisation Concert Featuring the Sal-Mar Construction

2011 On-Line Concert

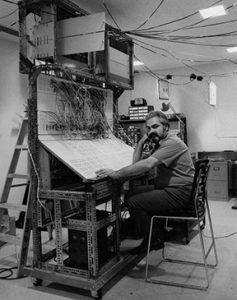

This special concert of improvised music featured a mélange of local musicians performing on a variety of traditional and new music instruments with the Sal-Mar Construction, built from the TTL boards of the ILLIAC II by Salvatore Martirano, Sergio Franco, and ILLIAC III designers Rich Borovec and James Divilbiss. The instrument, preserved at the Sousa Archives and Center for American Music, is believed to be the earliest interactive music synthesizer to combine the essential elements of human conversation and music improvisation into a continuous performance event, and this concert highlighted the unique nature of this early electro-acoustic instrument. Performers included Ken Beck on the Sal-Mar Construction, Dorothy Martirano on violin, Barry Morse on theremin, Jacob Barton on the utterbot, John Toenjes on computer synthesizer, Jason Finkelman on computer synthesizer and African instruments, and Jeff Zahos on percussion. This concert was sponsored by the Sousa Archives and Center for American Music in partnership with the University of Illinois’ OCE-ATLAS.