This paper is part of the Student Researcher Series which showcases research students have conducted using resources in the Student Life and Culture Archives.

Cassidy Burke is a junior in the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences studying history and communication with a minor in Spanish and a Digitization Assistant at the University of Illinois Archives. She summarized her project by saying, “I chose to research the discussion of sexual assault at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign during the 1970s and 1980s. My research demonstrates that a handful of brave UIUC women during this time were at the forefront of bringing the discussion of rape and sexual assault into the public space. Dissonance & Disinterest shows the way women shaped rape prevention on campus, and how their efforts, while ignored at first, left a tremendous impact.” Cassidy presented her research at the Ethnography of the University Initiative Conference in December 2015.

Introduction

On July 2, 1974 the rape hotline at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign received a call from a woman. The woman asked the hotline receptionist if she was being raped. The receptionist said, “No, are you?” The woman replied, “Yes-you should be. You don’t know what you’re missing.”[1] A day earlier, a woman called and asked if this was “the rape hotline where you call when you been raped or sexually assaulted, right?” The receptionist said yes, and the woman on the other end hung up. Three minutes later, the same number called back, but hung up immediately. Two minutes later, the same number called and instead a male voice said, “How big’s your pussy?”[2] A month earlier, a woman called the rape hotline after she experienced stomach pains following being raped. After the rape hotline tried multiple times to get back in touch with the woman, the woman revealed in a second phone conversation that five men gang raped her the night before; she was unsure whether or not to report the crime. She knew the man who forced her into this disturbing and unthinkable violence.[3] In the 1970s and 1980s, rape at the University of Illinois existed and created deafening silence surrounding sexual violence all over campus. Many woman and men who did call the rape hotline to report a rape often got cold feet and as demonstrated above, many students made a joke of the rape hotline, with crude or phony stories.

In 1966, a Champaign Country Grand Jury indicted Richard T. Callaghan, a nine-letter athlete at the University of Illinois for rape of a UIUC stenographer.[4] The case did not go to trial for four years, and Callaghan lived freely in Chicago: his life uninterrupted and reputation untainted by his crime. This was the largest rape case the Daily Illini covered up to this point, but not in a good way. The article did not discuss how wrong it was that Callaghan’s trial did not go to court for four years, or how Mary Gourley died two months following the attack; the article instead highlighted Callaghan’s triumphs and legacy in Illinois athletics, posted a large picture with the caption, “Richard T. Callaghan…nine letter athlete,” and only cared that the reader knew “Miss Gourley died of causes unrelated to the alleged crime.”[5] The author of this article, Robert Cooper, did everything in his power to clear Callaghan’s name and dismiss the crime. He used the word ‘alleged’ very frequently in his writing, and ended the article by clarifying Callaghan was only charged with being an accessory to rape. This skewed perspective of the severity of rape shaped how the University student body viewed the issue of sexual assault, but the University of Illinois was not alone in their thinking.

The root of rape as a societal norm stems from centuries of female subordination and male dominance, thus justifying rape in society. Dianna Scully and Joseph Marolla’s research reveals the motives of convicted rapists. The research overwhelming demonstrated these men raped to assert their dominance over women to be “macho” and to make her “totally submissive.”[6] These narrow definitions of masculinity were only amplified in fraternities. Patricia Yancey Martin and Roberta A. Hummer’s research reveals fraternities are structured in a way that women are commodities for brothers to use as they wish. Alcohol is used to “prey” on women to get them drunk, thus making sex more accessible to the fraternity men.[7] Given UIUC’s large Greek system, this could not be more prevalent during the 1970s and 1980s. Martin and Hummer argue, “that fraternities create a sociocultural context in which the use of coercion in sexual relations with women is normative and in which the mechanisms to keep this pattern of behavior in check are minimal at best and absent at worst.”[8] During the 1980s, 20% of college women across the country would be victims of campus rape along with 51% of college men who said they would rape if they could not be punished for it.[9]

This dissonance between wanting to create social change and actually creating social change is a struggle the University of Illinois, and many universities across the nation still face today. The scholarship surrounding sexual assault now often focuses on motives of rapists, methods for rape prevention, and a history of the consistent problem of rape on campus. My research took a different approach that combined all these idea, and I asked why there was a change in policy and what made the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign take a stand to prevent rape on campus in the 1970s and 1980s. While it is often the University administration that is applauded for policy change that ensures the safety and rights for all students, it was the women students during this time that ignited this change about discussing rape on campus that made the University administration listen. This journey ran into disinterested students and public dismissal of the severity of rape, but nonetheless forged its way through society’s broken system of values, and for the first time recognized the problem of campus sexual assault and how to prevent it in Urbana-Champaign.

Prior to the 1970s, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) had no programs, task forces, or committees that discussed the issue of sexual assault on campus. Sexual assault happened on campus, but the University and student body never gave sexual assault adequate attention. The Daily Illini, the student newspaper for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, published three different case articles with regards to sexual assault and violence on campus that demonstrate the lack of attention to rape on campus prior to the 1970s.

In late 1957, the DI published a few articles talking about rape involving Ralph Anderson; a community member of the Champaign-Urbana area, age 33, but was not a student. Three years prior in 1954, Anderson and Richard Emert were arrested for statutory rape of a 14-year-old girl. The men’s cases did not go to court for three years. Even more shocking, once November 22, 1957 rolled around, the Judge decided to defer the rape hearing for Anderson.[10] After this, The Daily Illini did not report any more on the ruling of this case for Anderson. It was not until January 1958 that Anderson’s name appeared again for his second charge of rape against Shirley Smith, age 28. On January 21, 1958, Police Magistrate Rex Davis dismissed the charges against Anderson for lack of evidence.[11] At this point, Anderson was on probation, thus meaning he was convicted for statutory rape in December. This would also mean he served less than two months for raping a 14-year-old girl. Moreover, when a motion was made to revoke Anderson’s probation in February of 1958, “Judge Morgan ruled Anderson should be allowed to continue on probation because his case did not warrant revocation.”[12] This striking series of unfortunate events in the Ralph Anderson cases just glimpses the surface of how the Champaign-Urbana community dealt with rape. The most fascinating aspect as to how the Anderson cases were portrayed in The Daily Illini gives an idea as to what the student body wanted to read about, and what The Daily Illini deemed newsworthy.

The Daily Illini clearly did not find the Anderson Cases important; the paper conveyed that perspective both in the way the story was not followed, as well as visually. To begin, the fact that The Daily Illini did not follow the Anderson case on statutory rape until the final verdict demonstrates inconsistency in what the staff deemed important for its reader. Furthermore, the phrases used to describe the Anderson cases were not very precise and varied slightly from article to article. For instance, the Anderson’s statutory rape charge appeared on November 19, 1957 for the first time. This article stated, “Both men are charged with rape of a Champaign girl in 1954.”[13] However, in an article published three days later, it says, “Charges originally arose in 1954 when the two were arrested for allegedly attempting to rape a 14-year-old Champaign girl.”[14] Being charged with rape and attempted rape are two very different things; yet, The Daily Illini used these two crimes as one in the same. By using the phrase “allegedly attempting” to describe Anderson’s action, The Daily Illini conveys an opinion on whether or not Anderson and Emert were guilty since these men were on trial for rape, not attempted rape. Also, articles that had Anderson’s name in the title showcased Anderson’s innocence: “Davis Dismisses Anderson Case”, “Deny Revocation in Anderson Case; Probation Okayed.” Conversely, when rape was mentioned in the title with regards to Anderson’s cases, his name was not in the title: “Rape Charge Trial Set for Thursday In Circuit Court”, “Judge Defers Rape Hearing.” The Daily Illini, explicitly or inexplicitly, associated Anderson with innocence and not rape based on the way they began their articles. By choosing to use and not use Anderson’s name in different scenarios, The Daily Illini humanized Anderson when he was innocent and dehumanized the concept of rape in a way that made the readers disassociate rape with a human being. Instead, readers associated rape as something to be dealt with by the courts, and not a crime that affects lives physically, mentally, and emotionally. As far as visually speaking, the stories in The Daily Illini on the Anderson case were small, brief, and always appeared on the third page or later.[15] The Anderson cases, along with the Richard Callaghan case discussed in the introduction demonstrate how rape at the University of Illinois and in the Champaign-Urbana area was not handled with the care or importance it warranted from the community.

Prior to the 1970s, the University of Illinois did not have any organizations or programs on campus to bring to light the severity of sexual assault. Because of this, the student newspaper for the University followed rape if they had no other stories to fill the gaps on their pages. The DI covered the cases when they went to court or warranted some sort of public news; otherwise, the conversation of rape was lost. This started to change in the 1970s. In the mid-1970s, a small group of UIUC women created the Women’s Student Union (WSU); these women were at the forefront for promoting the discussion of sexual assault on campus and in the community.

The Women’s Student Union (WSU) was created at the beginning of the 1974-1975 academic year. The WSU wrote out a variety of issues on campus they wanted to tackle, through the establishments of different task forces. The Health Care Task Force had a series of issues mainly regarding McKinley Health Center that they wanted to change for the upcoming year. Number four on their list of goals stated, “Approach the health center with a standardized procedure for handling rape victims.”[16] The Health Care Task Force seemed like a progressive movement for the women and the University of Illinois as a way of connecting student sentiment and women’s rights to University policy. Unfortunately, this part of the WSU Health Care Task Force sounded better on paper than in action. In January of 1975, the Women’s Student Union released its first newsletter. When it described the Health Care Task Force, the newsletter restated the mission of the task force as stated above, but followed it up by saying, “Thus far little else has happened.”[17] This short phrase unfortunately signified the disappointing lack of interest for women to serve on the Health Care Task Force, let alone fight for changes with McKinley Health Center.

This disappointing trend continued through the end of the semester and drastically changed the task force’s mission for the next school year. For the remainder of the spring 1975 semester, the minutes from the WSU meetings indicated the Health Care Task force was still making little progress. At the April 1, 1975 meeting, the secretary only wrote, “Health: not much up”[18] when all other task forces in the WSU had different projects in progress. In July of 1975, the WSU executive board released a welcome back letter for the 1975-1976 school year. The letter outlined different ideas and task forces for the upcoming school year, yet there was no mention of the health care task force.[19] The task force did not disappear completely according to the WSU Newsletter from January 1975- February 1976. The Health Care Task Force instead began focusing its attention more on, “breast and cervical exam, VD, birth control, female anatomy, and vaginal infections.”[20]

The WSU women decided to take a different route to tackling rape prevention by doing it themselves, without the need for University administrators. The WSU created Women’s Wheels, “a rape prevention service which gives rides to University women walking alone at night between 7pm and 2am.”[21] At this point in time, the WSU had 80 women volunteers that served Women’s Wheels as “drivers, navigators, and dispatchers.”[22] Women’s Wheels was one of the most successful efforts that came out of the Women’s Student Union; today it is known on campus as Safe Rides and Safe Walks. Women’s Wheels was one of the earliest forms of rape prevention services on campus, especially considering the University did not start its Coalition Against Violence and Rape until the 1980s.

Nonetheless, the fact that the WSU removed the conversation of rape from its Health Care Task Force due to low numbers of women working on the task force speaks volumes to how disinterested promoting sexual assault prevention on campus was even for women.[23] While many factors could play into why women were not motivated to promote the original health care task force initiatives, it is very likely the WSU chose to refocus their health care task force on different issues of women’s health because of the emergence of WAR (Women Against Rape) on campus around this time.[24] WAR specifically targeted the needed push for sexual assault prevention, leaving the WSU to channel their efforts into other areas of women’s rights that dealt with their sexuality.

Sexuality was not something discussed in a public setting very often, clearly demonstrated by a University regulation released in September of 1976 that “restrict[ed] sexuality from being discussed in any University buildings, thus eliminating any self-help clinics.”[25] A forum was held to challenge this new policy, which the WSU secretary referred to as, “ridiculous and probably unconstitutional ruling.”[26] This fire and blunt attitude written in the Women’s Student Union minutes started to emulate the growing activism at the end of the 1970s. In that same semester, the WSU sponsored its first “Sexist Pig of the Semester” contest. Women students were encouraged to nominate any advisors, professor, or instructors that they felt were sexist, and thus subjected these men to public humiliation.[27] This was the most progressive and rebellious movement by the WSU. Before, they mainly focused on helping other women and promoting women’s rights on a more administrative level. This contest demonstrated the growing heat in women’s students to fight back against their sexual repression and wanted the University’s attention.

The major turning point on the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign campus with regards to promoting sexual assault prevention came in September of 1979. On September 26, 200 University women protested in the streets in a march called, “Take Back the Night.” This march was part of a series of nationwide marches that started in 1978.[28] As advertised across campus, the protest’s purpose was, “To protest violence against women/To stand up for our right to be free from fear/ To proclaim our refusal to live in cages.”[29] While 200 hundred women filled the streets and proud supporters of the women’s safety movement voiced their opinions to stop sexual violence openly, 200 voices still only made up a small portion of campus. Nevertheless, 200 women chanting for their rights is still a large group to be fighting for the same end goal, especially when putting it in perspective that the WSU could not even sustain an adequate task force to confront policy and sexual assault three years ago. While this event seems to demonstrate a progressive time in the women’s rights movement at UIUC, Take Back the Night at the University of Illinois received very open backlash.

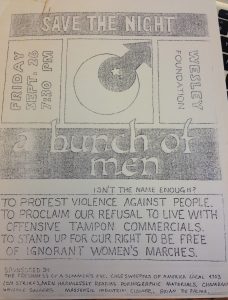

The Take Back the Night protest used flyers to promote and outline the purpose of the march and who organized it. An unknown person/organization, most likely male, decided to create another poster that mocked the event and the women who participated in the march. The poster entitled, “Save the Night” stated it wanted, “To protest violence against people/ To proclaim our refusal to live with offensive tampon commercials/ To stand up for our right to be free of ignorant women’s marches.”[30] This poster was a clear copycat of the original poster, and attacked women for wanting to stand up for their rights. Moreover, in the sponsors section of Save the Night, it listed “Cage Sweepers of America Local 4703” and “Men Harmlessly Reading Pornographic Materials,”[31] which directly referenced and degrade the Take Back the Night poster, as well as what the Take Back the Night hoped to accomplish. During the march, men shouted, “bad women” to those marching, as well showing blatant disinterest in why the women were marching.[32]

For this moment in history, it was not uncommon for University initiatives to be so far removed from these women who wanted to influence change on campus and women’s rights; however, following an incident at UIUC in 1981 involving fraternity members from Delta Tau Delta and their sexual misconduct with Alpha Phi sorority members, a spark ignited amongst the student body. Women students wrote to local newspapers exclaiming their disgust and frustration over how the University of Illinois handled the incident, while others scoffed at the University zero tolerance for sexual violence. The incident garnered the University attention women activists desired, and the University of Illinois made strides to prevent rape and sexual assault on campus for the first time.

Delta Tau Delta is one of the oldest fraternities on campus and in November of 1980 at an exchange with Alpha Phi, 5 Delta Tau Delta brothers got completely naked and pushed themselves onto Alpha Phis. The women were not raped, but were absolutely sexually assaulted by the brothers. The Interfraternity Council evicted 26 brothers from the Delts house related to the incident and the uproar over the punishment for the campus’s top fraternity was tremendous. [33] The Delts Incident divided campus in half. On the one side, University students and community members all over campus supported how seriously the University and Council treated the incident, but completely disagreed how they punished the Delts. The Delts who removed their clothes and jumped on the women were evicted from the house and also forced to volunteer at Women’s Wheels. The WSU wrote they were very concerned with having such men helping to drive and escort women home late at night after they clearly sexually assaulted the women of Alpha Phi. The WSU also criticized the Interfraternity Council and University for protecting the men by stating, “Without the protection afforded to fraternity by the University, these individuals may have faced criminal prosecution.”[34] The passion and fervor that the Delts Incident elicited amongst women students was exponential compared to talking about sexual assault prior to the 1980s. The Take Back the Night march at the end of 1979 was the women’s way to establish a sense of camaraderie amongst them. They stood together to show their strength to stop rape on campus; The Delts Incident turned this strength into demands for the University to take a stand with them.

On the other side of the Delts Incident, angered and appalled University community members supported the men of Delta Tau Delta, and passed it off as “just a couple of drunk guys prancing around naked.”[35] This was not just the sentiment of one angry father, but also a former senator and Delta Tau Delta brother. While interviewing the ex-senator, a reporter said that the Alpha Phis “feared for their life” to which the former senator retorted, “Tough buns, then. Everyone knows that college guys can do anything they want.”[36] This victim blaming did not only stem from men, but women as well. Julie Zichterman, a student and friend of Delta Tau Delta brothers stated, “If the remaining Alpha Phis were “afraid for their life,” or for their safety, then why didn’t they go home with their sisters and what were they doing there that late in the first place?”[37] Society continuously blamed women for staying out late and wearing “provocative clothing” (especially following the Sexual Revolution) because apparently it was the women’s responsibility to not awaken the animalistic nature of men to take anything they want; it was to many a “normal reaction” for men.[38]

By the 1980s though, some women started to combat this notion and its absolute ridiculousness. Valerie Cornelius, another student at UIUC stated in her letter to the paper, “Then here comes Zichterman with the old tactic of blaming women involved…Is she saying that women should go to and leave parties in groups (of more than six) to stay out of trouble…Is she inferring that women who stay late at parties, even when there are six of them, are asking for trouble and deserve what they get?”[39] This difference between the two women perfectly emulates the divide on campus between the current societal norms and how women wanted it to change during the feminist movement. From there, the University finally listened to the campus outcries. Between the Delts Incident of the 1980-1981 school year and the FBI naming the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign the second most dangerous campus in the nation in 1981[40], the women activists of the 1970s and 1980s finally got the University’s attention. While this was all spiraling out of control, the University finally established the Coalition Against Violence and Rape (CAVR) to combat campus rape at the administrative level. [41] While it was a student run group, they worked closely with administrative sponsors to create change on campus.

During the 1980s, the Women’s Resource Center started to gain prestige around campus, them at night and more advertisements around the Women’s Wheels program.[42] In 1983, the CAVR issued a “Women’s Safety Questionnaire” that gave light into how aware women are of their safety on campus. The survey revealed 44.7% of University women students were victims of rape or knew victims of rape. It also showed only 7.5% of women reported ever seeing Student Campus Service Officers patrolling campus. All women surveyed said they’d like to see more of these officers to make them feel safer.[43] The University also organized a number of group “Night Walks” in the early 1980s involving campus volunteers that took place to identify areas on campus that are dimly lit and need more light to create a safer environment. The University installed the emergency phones still seen on campus today and distributed pamphlets to students outlining paths on campus that are well lit with emergency phones.[44] While all of these efforts were fantastic ways of increasing safety for women on campus, the most important innovation that came out of the late 1980s was the establishment CARE: Committee on Acquaintance Rape Education.[45] It was the first peer-facilitated workshop for University students that focused on rape prevention and acquaintance rape. Not only did the University make an effort to make physical changes to the campus community to increase women safety, they decided to make an environmental change that shook the taboo silence from rape on campus. This program evolved over the past few decades and is known today amongst U of I student as FYCARE.

Conclusion

While the University of Illinois administration can be commended for the action it took during the 1980s to make campus a safer place for women, the real heroes of this story are the women students that spoke up amidst the deafening silence around sexual assault at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The reality of the situation was rape was not something that happened to “other people” at the University of Illinois. There was a perpetual, ignorant cloud that surrounded rape at the University of Illinois; women were constantly victim blamed and mocked for their social activism to fight against sexual violence. This other-centered view and the mockery that followed discussing rape with college students caused a gridlock of activism and ideas. This perpetual fog did not discourage the Women’s Student Union, the Women’s Wheels volunteers, the Rape Hotline receptionists, WAR, the women who wrote into local newspapers voicing their anger over the lack of attention to sexual assault, or any of the women who marched in Take Back The Night. These brave women brought the discussion of rape and sexual assault into a public space despite the initial backlash and disinterested University administrators and community members. Their unanswered efforts did not desist and while it is tragic they needed to wait for a horrifying campus incident that hit close to home, they used it as a springboard to elicit the dire change needed in campus policy and started a revolution in the discussion rape on campus through the establishment of the Coalition Against Violence and Rape.

The fight against sexual assault is not over. 20% of college women were victims of sexual assault during the 1980s; today that percentage remains the same.[46] The “It’s On Us” campaign is a movement on college campuses across the nation that is continuing the efforts like the UIUC women during the 1970s and 1980s. “It’s On Us” is on a mission to stop sexual violence against women and men, garnering the attention of public figures and celebrities to endorse the campaign.[47] This campaign is an amazing national effort that takes an absolute stand against rape, yet is only undermined while the Safe Campus Act remains in Congress.

If passed, the Safe Campus Act would limit the consequences, such as expulsion, for university and college students who commit sexual assault crimes, unless the victims decides to press charges with law enforcement offices.[48] The Safe Campus Act, quite ironically named, is only safe for rapists and absolutely undermines the rights of victims. At the beginning, the North-American Interfraternity Council and National PanHellenic Conference endorsed the Safe Campus Act in order to protect students on campus accused of rape. In early November of 2015, Alpha Phi was the first national sorority to disband from their National Panhellenic Conference and state their opposition to the bill.[49] This created a spiral effect and sororities across the nation followed their lead, causing the NPC to withdraw their support as well.[50] This bill demonstrates the severe misunderstanding of people, men specifically, around the victimization of women on a daily basis. The bill is designed to protect men from expulsion as if going to college is a right for all people that cannot be taken away without due process. Higher education is a privilege; safety and security for women is a right.

Rape is still a problem on college campuses, which absolutely includes the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The fact that the issue persists does not undermine the efforts of the University women during the 1970s and 1980s in any way. Without these women breaking the silence around sexual assault, the vehement backlash to the Safe Campus Act from people across the nation today would not be possible. Ultimately, this history of talking about rape on campus is just a small piece of the bigger picture of women standing up for themselves, breaking horrible societal and gender norms, and changing the world not just for their generation, but every generation to come.

[1] Rape Hotline Narrative Report Form, 2 July 1974, Box 39, Folder Rape Hotline Narrative Reports, 41/69/331 Women’s Liberation-Women Against Rape 1969-79, Student Life ad Culture Archives, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. (Known As SLCA UIUC)

[2] Rape Hotline Narrative Report Form, 1 July 1974, Box 39, Folder Rape Hotline Narrative Reports, 41/69/331 Women’s Liberation-Women Against Rape 1969-79, SLCA UIUC.

[3] Rape Hotline Narrative Report Form, 3 June 1974, Box 39, Folder Rape Hotline Narrative Reports, 41/69/331 Women’s Liberation-Women Against Rape 1969-79, SLCA UIUC.

[4] “Nine letter varsity star, Athlete tried for rape,” The Daily Illini, 16 October 1970, 3.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Diana Scully and Joseph Marolla, “ ‘Riding the Bull at Gilley’s’: Convicted Rapists Describe the Rewards of Rape,” in Violence Against Women: The Bloody Footprints, edited by Pauline B. Bart and Eileen Geil Moran (California: SAGE Publications, Inc., 1993), 38-39.

[7] Patricia Yancey Martin and Robert A. Hummer, “Fraternities and Rape on Campus,” in Violence Against Women: The Bloody Footprints, edited by Pauline B. Bart and Eileen Geil Moran (California: SAGE Publications, Inc., 1993), 122-125.

[8] Ibid., 115

[9] Scully et al., “Riding the Bull,” 27.

[10] “Judge Defers Rape Hearing,” The Daily Illini, 22 November 1957, 3.

[11] “Davis Dismisses Anderson Case,” The Daily Illini, 21 January 1958, 3.

[12] “Deny Revocation in Anderson Case; Probation Okayed,” The Daily Illini, 11.

[13] “Rape Charge Trial Set for Thursday In Circuit Court,” The Daily Illini, 19 November 1957, 3.

[14] “Judge Defers Rape Hearing,” The Daily Illini.

[15] Please see endnotes 11 through 14

[16] WSU Health Care Task Force, 1975, Box 1, Folder WSU Brief History/statement of Purpose 1975, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[17] Women’s Student Union Newsletter, January 1975, Box 1, Folder 2, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[18] WSU Notes, 1 April 1975, Box 1, Folder 2, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[19] WSU Welcome Back Letter, 21 July 1975, Box 1, Folder 2, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[20] WSU Newsletter, January-February 1976, Box 1, Folder WSU 1975-1976, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[21] Ibid, 2.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] YWCA-WAR Declaration of Intent, Box 29, Folder YWCA-CCWAR 1976, 41/69/331 YWCA Subject File, 1902-2003, SLCA UIUC.

[25] WSU Minutes, 15 September 1976, Box 1, Folder WSU 1976-1977, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “Sexist Pig of the Semester” Poster, 1976-1977, Box 1, Folder WSU 1976-1977, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[28] Dana Cvetan, “Women march to protest violence on local streets”, newspaper article, 29 September 1979, Box 1, Folder WSU 1979-1980, Box 1, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[29] Take Back the Night poster, 1979, Box 1, Folder WSU 1979-1980, Box 1, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[30] Save the Night poster, 1979, Box 1, Folder WSU 1979-1980, Box 1, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Cvetan, “Women march to protest violence on local streets.”

[33] Mick McNicholas, “26 Delts told to move out of UI House”, newspaper article, 4 February 1981, Folder Violence Against Women Deltas Incident 1981, Box 1, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[34] Women’s Student Union, “IFC Ruling Wrong for Delts”, letter to the editor, 12 February 1981, Folder Violence Against Women Deltas Incident 1981, Box 1, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[35] Don Baraglia, “Ex-senator thinks Delts will return in the fall”, column article, 5 February 1981, Folder Violence Against Women Deltas Incident 1981, Box 1, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Julie Zichterman, “Delts’ reputation is wrong”, letter to the editor, February 1981, Folder Violence Against Women Deltas Incident 1981, Box 1, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[38] A.F Schiff, MD, “Rape in the United States,” Journal of Forensic Science Vol. 23 No. 4 (Oct 1978): 846.

[39] Valerie Cornelius, “Don’t blame Alpha Phis”, letter to the editor, 12 February 1981, Folder Violence Against Women Deltas Incident 1981, Box 1, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[40] “Crime on Campus”, Parade, January 4, 1981, Folder Police, Box 2, 37/4/805 Police Issuances, University Archives (Main Library), University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. (Known as ML UIUC)

[41] Coalition Against Violence and Rape Mission and Purpose, Box 1, Folder Coalition Against Violence and Rape 1980, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[42] Women’s Wheels Poster and WhistleStop Poster, Folder Rape Prevention, Box 2, 37/4/805 Police Issuances, ML UIUC.

[43] Women’s Safety Questionnaire, 1983, page 3, Folder Coalition Against Violence and Rape 1980, Box 1, 41/66/100 Women’s Student Union Records 1974-1984, SLCA UIUC.

[44] Michele Louzon, “Perilous area locations sought in ‘Night Walks’”, Daily Illini, 5 October 1982, Folder News clippings 1977-1984, Box 6, 41/3/10 Women’s Resources and Services Subject File 1964-1991, SLCA UIUC.

[45] CARE Facilitator Application, 1987, Folder RAP Committee-Rape Awareness 1982-1988, Box 7, 41/3/10 Women’s Resources and Services Subject File 1964-1991, SLCA UIUC.

[46] Tyler Kingkade, “Campus Rape May Be ‘Worse Than We Thought,’ Study Shows”, The Huffington Post, 20 May 2015.

[47] “It’s On Us”, accessed 13 December 2015, itsonus.org

[48] Tyler Kingkade, “Fraternity Groups Push Bills To Limit College Rape Investigations”, The Huffington Post, 4 August 2015.

[49] Tyler Kingkade, “Alpha Phi Becomes First Sorority To Say It Doesn’t Support Safe Campus Act”, The Huffington Post, 12 November 2015.

[50] Walbert Castillo, “National sorority, fraternity groups withdraw support from Safe Campus Act”, USA Today College-University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 17 November 2015.