It is not easy to set the boundaries to what should or should not be included in the category of Jewish Encyclopedias of Russia and Eastern Europe. In terms of the scholarship content, as the individual entries will make clear, there was a heavy reliance upon Jewish scholarship in Germany, which is not included in this guide for reasons of regional definition. It was in Eastern Europe (specifically Poland) that the first attempts at publishing a modern, general knowledge encyclopedia took place in Hebrew, for example. In Yiddish also, planning for a modern, general-knowledge (as well as Judaism) focused encyclopedias took place here, but the resulting multi-volume publication, the Algemayne Entsiklopedye, was produced in Paris after 1930. For readers who want to know more about Jewish encyclopedias outside the region of Russia and Eastern Europe, please consult the Encyclopedia section (pages 1-7) of Shlomo Shunami’s Bibliography of Jewish Bibliographies (Jerusalem, 1965) for a thorough and useful list. Many of these are in Hebrew, produced before WWII either in Eretz-Israel or New York City. Shalami’s bibliography is itself a seminal work in the field, serving as an important first step toward serious research in any topic having to do with with Jewish history, literature, sociology, biblical studies, relations with Gentiles, etc. It is a bit weak on the Holocaust, since it was still a relatively new field when Shunami’s volume came out. Now almost fifty years old, it is hardly outdated. Before WWII, several publications were produced by Jewish editors about worldly and Jewish topics in the vernacular languages of Eastern Europe. Perhaps the best known is the Evreiskaia Entsiklopedia published in St. Petersburg at the beginning of the twentieth century, but there was a Jewish encyclopedia published in Hungarian and in Serbo-Croatian, as well as many lesser known multi-volume sets in Russian. Undoubtedly many more would have also been produced in Polish if not for the Holocaust. In general the guides have been arranged chronologically, except when they have direct contextual relationships, such as with the Russian-language Jewish encyclopedias.

Evreiskaia Entsiklopediia. Svod znanii o evreistvie i ego kul’turie v proshlom i nastoiashchem.

Editors: L.Ī. Kat︠s︡enelʹson (with S.M. Dubnov, v. 1; with D.G. Gint︠s︡burg, v. 2-8; with A.I︠A︡. Garkavi, v. 9-13). S.-Peterburg. Izdanīe Obshchestva dli︠a︡ nauchnykh evreĭskikh izdanīĭ i Izdatelʹstva Brokhaus-Efron, [1906-13]. 16 vols.

U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference Slavic 296.03 Ev72

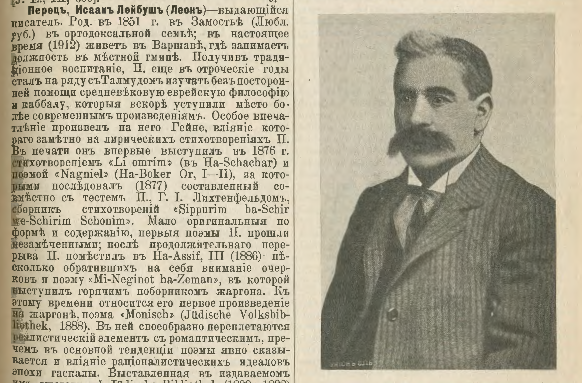

The Evreiskaia Entsiklopedia is the most detailed and thorough compilation of modern knowledge of Jewish history, society and traditions in the Russian language reflecting a largely secular, Jewish world view. It is a 16-volume set that covers biblical and historical figures, religious philosophy, Talmud, history, songs, and holidays. Secular rulers of Eastern European countries are also included. As the editorial board, a veritable who’s who of turn-of-the-century Russian Jewish leaders, stated in the intro to the first volume, the assignment of the ‘Evreiskaia Entsiklopediia’ is to apply modern science toward the investigation of Judaism and Jews; to explore history and culture and present an accurate picture of the state of Jews in all contemporary countries. Articles have bibliographies, but the citations are mostly in German. There is a list of abbreviations at the beginning of the first volume. Volume 16 contains a detailed index to all of the other volumes.The longer entries are author signed, but not all. The encyclopedia was initially modeled after the 12-volume Funk and Wagnall’s Jewish Encyclopedia published in New York in 1901, but quickly moved in a direction reflecting a Russian-oriented cultural frame of reference. For example, both publications have numerous biographical entries under the name of Adler, but they are mostly different, reflecting the desire to cover different individuals consequential to the particular national cultures. Also, while the Russian version reflected the modern, secular perspective prevalent among educated, acculturated Western Jews, it also offered considerably more traditional, religious subject matter, which was at least in part a product of the comparative difficulty of acculturating into a less welcoming Russian milieu as well as the by-product of growing national pride as a rebuttal to Russian antisemitism.

Kratkaia evreiskaia entsiklopediia.

Itzkhak Oren, Mikhael Zand. Ierusalim: Keter, 1976. 7 v.

U of I Library Call Number: Main Stacks Reference 296.03 K865

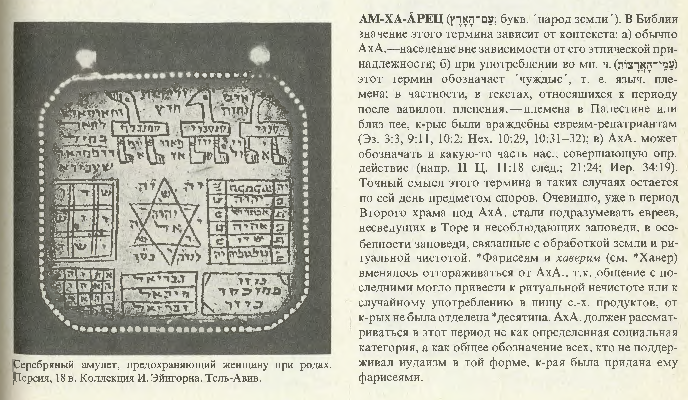

The entries in this seven-volume set don’t have bibliographies but the end of each volume has a list of terms. There are typically some internal references, especially if they pertain to biblical texts. Excellent photographs are used throughout. Initially published in 1976, the seventh volume came out in 1994, after the USSR had collapsed. The last issue goes up to “Socialism,” so likely additional issues were planned. There are two slim supplementary issues published in 1992 and 1995, but these do not focus on the letters after S but rather offer a general update. The entries are generally short and are not individually signed. Also modeled on American publications, the Kratkaia evreiskaia, in comparison to the Evreiskaia above, represents the tremendous change in Jewish circumstances from the turn of the twentieth century to the 1970s. The Evreiskaia was published in the capital of the Russian Empire by acculturated Jews. It was aimed at secularizing and educating their coreligionists: a traditional, religious community conversant in Yiddish but increasingly learning Russian. The publishers had to deal with Russian imperial censorship, but the approach is quietly geared against antisemitism and is clearly apologist (if Jews are backward, it is because of the discrimination they faced in the past, etc). The goal is to foster acceptance of Jews through knowledge in order to earn a place in Imperial Russia, thus the tone is full of hope for the future and faith in secular modernism. This is night and day from the Kratkaia. Published in Israel beginning in the 1970s, it is stridently Zionist, celebratory of the Jewish state and Jewish tradition. The longest entry in the encyclopedia is for the Israeli War of Independence, much longer than entries for God or antisemitism, for example. It is published in Russian because it is aimed at a diaspora Soviet Jewish community that has become completely acculturated into Russian culture and language (largely forgetting Yiddish and having no access to Hebrew) but that has been largely rejected from Soviet society by new waves of antisemitic discrimination after WWII which has caused Soviet Jews to demand exit visas out of the USSR for Israel. It rejects any notion of acculturation in the Soviet context, reflecting a post-Holocaust ambivalence toward secular modernity. The Kratkaia thus aims to inform these forcefully lapsed Jews of Hebrew culture and language to construct a new Jewish identity: the Kratkaia is full of biblical figures, geographical locations in Israel (describing the Jewish population there), prayers, and Jewish organizations. Many entries are Hebrew words transliterated into Russian, followed by Hebrew spelling and Russian translation, designed to teach Hebrew to Russian-speaking Soviet Jews.

Rossiiskaia evreiskaia entsiklopediia.

Herman Branover, ed-in-chief. Moscow: Russian Academy of Natural Sciences/Israel-Russia Encyclopedia Center, 1994.

U of I Library Call Number: International & Area Studies Russian Reference (Slavic) 909.04924047 R7363

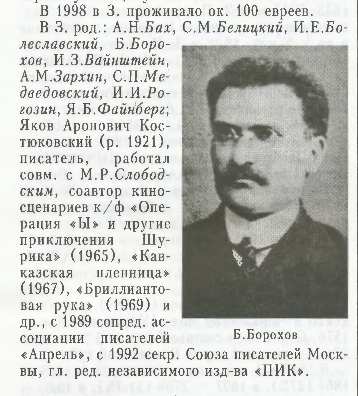

The first volume of the Rossiiskaia was published in 1994, already after the Soviet collapse and when the Kratkaia was completing its final volume. The first three volumes of the six-volume set, published in 1994, 1995, and 2000, are strictly biographical. There are no images in the first three volumes, nor is there an index, but at the end of volume three are several appendices including a glossary of terms and several lists of commonly used abbreviations.The entries are not individually signed in the first three volumes, however, more bibliographical content is provided within the individual entries, particularly for individuals, whose works are typically listed in full. Entries in volumes four through six are historical and regional/local in nature and are accompanied by images. Particular emphasis is placed on places, and their details typically include lists of prominent people who were born there.They begin again at the start of the alphabet in volume four, and in contrast to the first three volumes, are individually signed by contributors. These three volumes are full of place names and descriptions, including population statistics, secular and religious town leaders, etc. They were published upon the completion of the first three, in 2000, 2004 and 2007. Thus, the second half of the Rossiiskaia is quite contemporary, seeking to capture a sense of post-Soviet Russia. At the end of volume six are again lists of abbreviations and a glossary of terms, but no index. Contextually, the Rossiiskaia evreiskaia continues the conversation begun at the turn of the century by the Evreiskaia, rebutting the position taken by the Kratkaia. As is indicated by the name and stated explicitly in the introduction, the editors of the Rossiiskaia dedicated the encyclopedia (and thereby expressed their ideological direction) to the important role that Jews had played in the history and development of Russian civilization specifically, and world civilization secondly and more broadly. This is a direct confrontation to the Zionist perspective in the Kratkaia. It is a declaration of continued faith in the diaspora, as well as the idea of a Jewish civilizing mission and thus, implicitly, integration into the wider, non-Jewish society. Similarly, the editorial board, whose chief adviser was Sir Isaiah Berlin, deliberately departed from biblical (read Zionist) definitions of who is or is not a Jew for purposes of inclusion in its pages precisely because the Russian-Soviet context was so complex in terms of inter-marriage and lapsed religiosity. Likewise, while paying heed to the reality of the borders of the Russian Federation, the editors consciously included Jews from historical Russian civilization, which for them included everything from Congress Poland to Harbin in Manchuria.

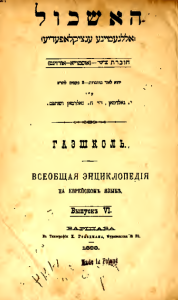

ha-Eshkol:General Encyclopedia

Warsaw, 1888: A.S. Freidberg, editor. Y. Goldman, publisher. 392 pp.

Warsaw, 1888: A.S. Freidberg, editor. Y. Goldman, publisher. 392 pp.Encyclopedia of general knowledge and history from a East European Jewish perspective published in Hebrew in 1888. Available online at http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00098560/00001/3j and at http://ia600306.us.archive.org/24/items/haeshkolallgemay00rabi/haeshkolallgemay00rabi.pdf. This was the first general knowledge encyclopedia printed in the Hebrew language. Although most of it’s subject matter is Jewish religious issues and contemporary, secular knowledge, it was an important publication for Zionists. It was begun by Avraham Shalom Friedberg, a man who was deeply affected by the pogroms of 1881 in Russia. As was the case with several modern Jewish encyclopedias published in mid to late 19th century in Germany, on which this was partly modeled, it was not finished, breaking off without completing even the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet (even though it included almost 800 columns of text). Because it was published in the Russian Empire the front page was required to be in Russian, although title half pages in Polish and German appear at the end of the volume. There is no index. Most of the entries are accompanied by titles and terms transliterated into Latin script.

Magyar Zsidó Lexikon.

Budapest: A Magyar Zsidó Lexikon Kiadása, 1929.

U of I Library Call Number: Oak Street Facility 296.03 M277.

Produced in interwar Hungary, this is a highly compact, single volume encyclopedia of over one thousand pages that focuses on Jewish-related topics in the Hungarian language. Like other such compilations of modern knowledge, it is heavily focused on the Hungarian national cultural milieu, into which Hungarian Jews before the Second World War were assimilated. It also seeks to combine biblical scholarship with modern academic trends, and references very heavily upon German-Jewish scholarship, which was very common among Central European Jews (and in general) at the time. There are thousands of short entries describing particular Hungarian Jews and Jewish settlements in Hungary (overwhelmingly from about 1850 until the 1920s). As such, it serves as an important memorial to the history of Jewish culture in Hungary. The entries in the encyclopedia are listed alphabetically and displayed in two columns. The bibliographic references within the individual entries are helpful and appear most of the time, particularly for the longer ones. Entries are typically autographed but not signed, which is not useful any longer for bibliographic purposes.The entire publication is currently available online as well, at http://mek.oszk.hu/04000/04093/pdf/.

Leksikon Judaizma i Kršćanstva.

Oleg Mandić. Zagreb: Matica Hrvatska, 1969.

U of I Library Call Number: Oak Street 296.03 M31l

Entries in this volume are organized like in a dictionary, with the individual terms often given their phonetic origins, grammatical function, part of speech, etc. After a brief introduction, bibliography and list of abbreviations, the rest of the volume contains listed descriptions, organized alphabetically. There is no index and only a very basic table of contents at the end of the volume. This is a dictionary of descriptions of people, places and things from the Old and New Testaments, as well as from the Jewish and Christian traditions. As such it is not strictly speaking concerned solely or even primarily with Judaism, but rather with providing a Serbo-Croat reading audience in an atheist country a piece-meal insight into faiths that they are officially not to believe in. Published in 1969 at the height of the Titoism in Yugoslavia (and with very few Jews surviving in the country), the audience of Mandic’s work is clear. Most of the descriptions are presented matter-of-factly, although some reflect thinly-veiled sarcasm (for example the description of Mucenici, martyrs). Mandić himself, an Auschwitz survivor and anti-fascist agitator in wartime Croatia, provided here the standard Marxist interpretation of religion. Given his perspective from his other writings at the time, it would not be an exaggeration to call this work anti-religious propaganda.