By Anoosheh Ghaderi, graduate student in French

Letter from Marcel Proust to Daniel Halévy, [19 July 1919] [1]

My dear Daniel

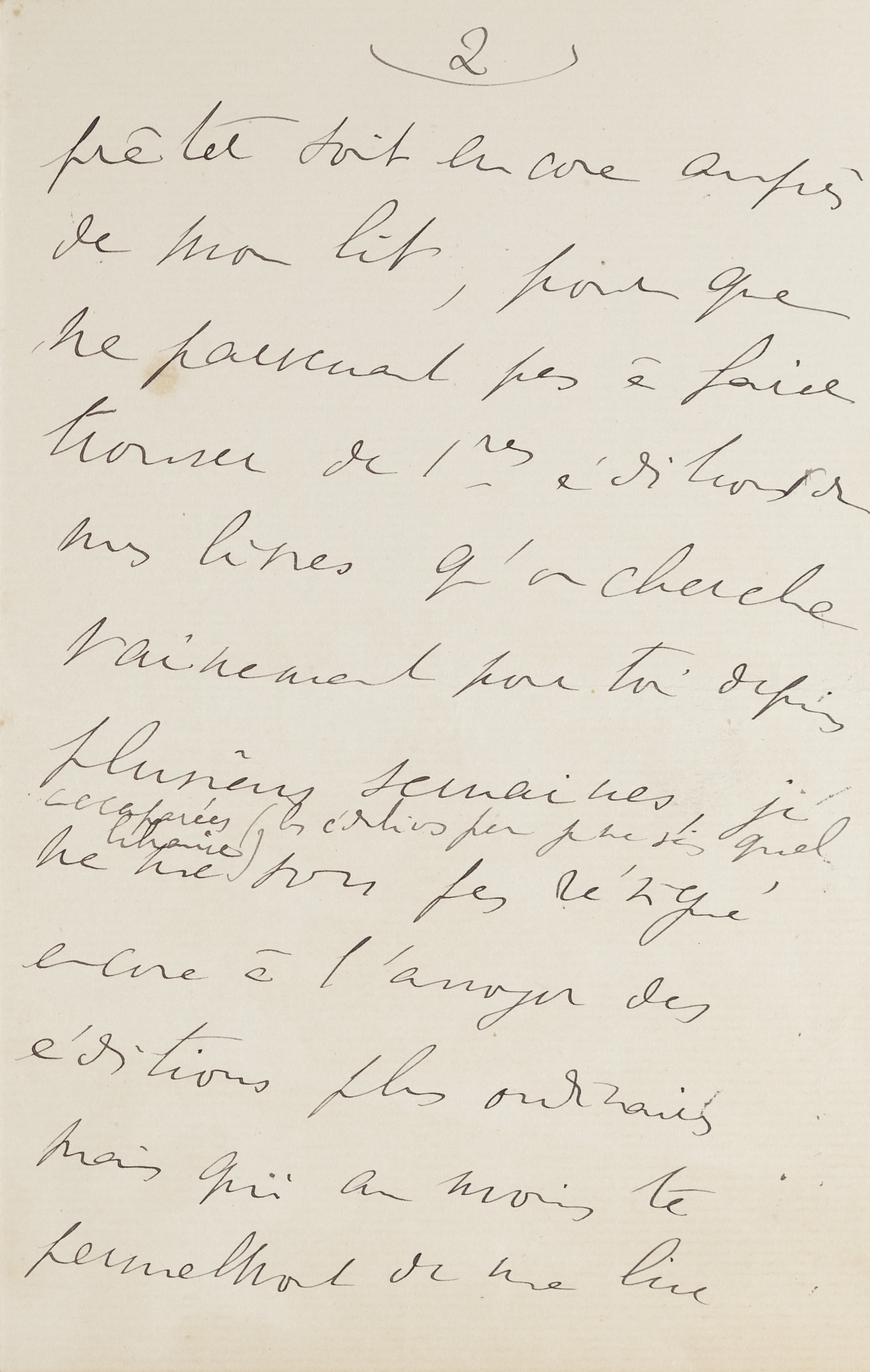

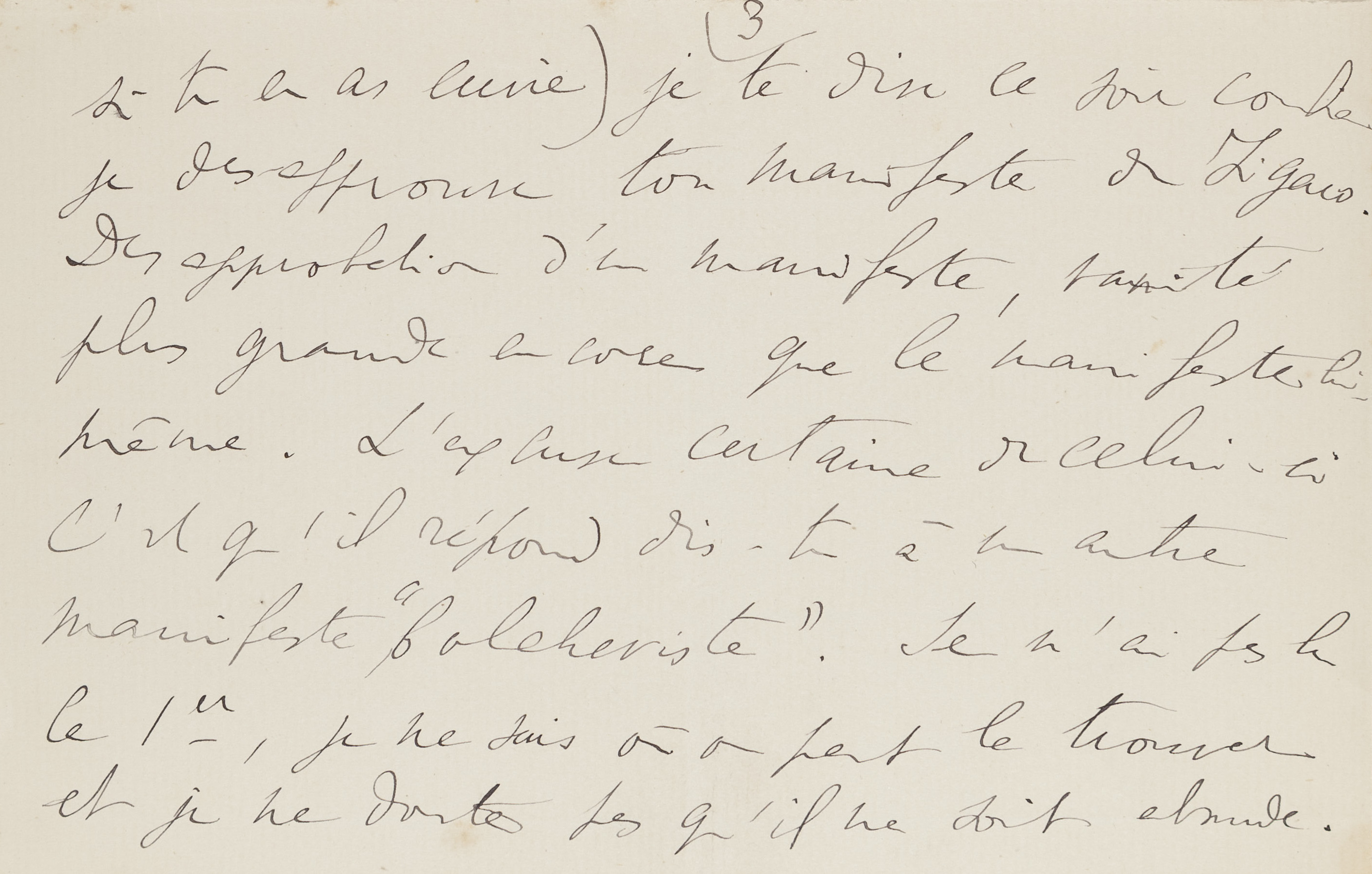

While I’ve had, for so long, such useful things to write to you (only a near death state has prevented me from writing to tell you all that I think of your admirable book [2]: this is why the booklet that you were so good to lend me [3] is still beside my bed, and also why, being unable to locate first editions of my books for you, despite having had people search in vain for many weeks [(]the editions being monopolized by I don’t know which bookseller), I have not yet resigned myself to send you the more ordinary editions that would have at least allowed you to read my work should you feel like it), [I have to] [4] tell you tonight how much I disapprove of your manifesto in the Figaro [5]. Disapproval of a manifesto, an even bigger vanity than the manifesto itself. This one was mainly written, according to you, in response to another “Bolshevist” manifesto [6]. I haven’t read that other one, I don’t know where it can be found and have no doubt it is absurd.

But, if I were less tired, I would find no less absurdity in the manifesto of the Figaro. Any righteous thinker would agree that we lose the universal value of a work by denationalizing it, and that it is at the pinnacle of the particular that the general blossoms. But, isn’t it also true that we strip away the general and even national value of a work by trying to nationalize it? The mysterious laws that preside over the blossoming of aesthetic truth as well as scientific truth are made faulty, if an outside reasoning interferes at the outset. The scientist who brings the highest honor to France through the laws that he brings to light would cease to honor his country if he sought this honor and not the truth alone; he would no longer find the unique relation that is a law. I am embarrassed to state such basic things, but I cannot understand that a mind like yours seems to not take them into account. That France should preside over all literatures of the world: we would weep for joy to learn that such a mandate had been given to us, but it is a bit shocking to see ourselves arrogate this task [7]. Such “hegemony” born from “Victory” involuntarily calls to mind “Deuthsland [sic] über alles” [8] and is slightly unpleasant for that reason. The character of “our race” [9] (is it truly correct French, to speak of the “French” “race”?) used to consist in melding such pride with more modesty.

No one admires the Church more than I do, but to speak like a kind of reverse Homais [10] and say that the Church has been the guardian of all advances of the human mind throughout time [11] is a bit much. It is true that there are “non-believing” Catholics. But such people, among whom Maurras is perhaps the most prominent, were no great help to French justice at the time of the Dreyfus affair. Why take such a contentious tone regarding other countries in matters such as literature, where persuasion alone rules? You [12] repeatedly say, “it is our understanding” (in the sense of, “we affirm without accepting a reply”). This is not the tone of “soldiers of the Spirit” [13]. In fact, even for a manifesto, in wanting to be so utterly French, you have adopted a Germanic tone. I don’t need to tell you that if I knew the “Bolshevist” manifesto, I would have certainly found it a million times worse than yours. But the main problem with yours is its being a manifesto. No manifesto can honor France, and serve it as well, as your works already do.

Your admirer and friend

Marcel Proust

[1] Letter catalogued as Proust-Series 7 (Items by Proust) / Item Proust 75-001, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. P. Kolb dated this letter to the evening of 19 June 1919, based to the reference to “your manifesto in the Figaro”.

[2] (Note by P. Kolb) The book in question is Charles Péguy et les Cahiers de la Quinzaine (Paris: Payot, 1918), published on 3 October 1918.

[3] (Note by P. Kolb) Halévy had a booklet made of Proust’s article entitled “Sentiments filiaux d’un parricide” in 1907. Because the Nouvelle Revue française lost the only version of this article that Proust had, he asked Halévy to lend him the booklet in December 1918, in order to assemble the collection Pastiches et Mélanges. See Proust’s letter to Halévy from [shortly after 5 December 1918].

[4] Proust seems to have omitted a few words here, after his long parenthesis.

[5] (Note by P. Kolb) The text in question appeared under the heading “Pour un parti de l’intelligence” [Manifesto for a Party of Intelligence] in Le Figaro’s literary supplement on 19 July 1919, on the front page.

[6] (Note by P. Kolb) The Manifesto of the French Communist Party had appeared in L’International on 7 June 1919.

[7] The 19 July 1919 manifesto listed among its ambitions the establishment of the “intellectual federation of Europe and the world under the aegis of victorious France, the guardian of all civilization.”

[8] “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles” is the first verse of the “Deutschlandlied,” the anthem of Austro-Hungarian Empire in the 19th Century. The song was a popular chant for German troops during the First World War; it was adopted as German national anthem in 1922.

[9] “We believe – and the world believes with us – that our race is destined to defend the spiritual interests of mankind. Victorious France wants to reclaim its sovereign place in the order of spirit, which is the only order by means of which a legitimate domination is exercised.” (“Pour un parti de l’intelligence”)

[10] Homais, a character in Flaubert’s novel Madame Bovary (1856), is a caricature of bourgeois republican secularism.

[11] “One of the preeminent missions of church, over the centuries, has been to ward human intelligence against its own mistakes, to keep the human spirit from self-destruction, to prevent doubt from attacking reason, to preserve thought as the right and privilege of man.” (“Pour un parti de l’intelligence”)

[12] Here Proust uses plural form of you in French (“vous”) to refer to all who signed the manifesto, whereas in the rest of the letter he uses the individual and informal “tu” to address Halévy.

[13] This phrase does not appear in the “Pour un parti de l’intelligence” manifesto.

This letter was written by Proust to his school friend Daniel Halévy, with whom he maintained a lifelong correspondence after they collaborated on founding literary journals in their youth. Despite their diverging world-views, their correspondence is full of enthusiasm for discussion over any subject as well as mutual respect and admiration. Proust begins most of his letters expressing how much he has to say to Halévy. This letter also begins with such a statement. Proust is passionate in expressing his disapproval of Halévy’s political stances about the role of literature and art after World War I, but he paradoxically also states that he admires Halévy’s books as works that can truly bring honor to France.

In this letter written on 19 July 1919, Proust expresses his opinion over the issue of the day. In the aftermath of World War I and especially in 1919, a quarrel broke out between intellectuals of the French left and right, regarding the national responsibility and role of art and literature. Halévy, affiliated with the political right, signed a new manifesto for a “Party of Intelligence” published in that day’s Le Figaro. The manifesto called for a restoration of “French” and Catholic values in art and thought, and for the promotion of these values across Europe and the world, befitting France’s position among the victors of the war. It was signed by writers aligned with the far right such as Charles Maurras, as well as some supporters of Dreyfus during the Affair, such as Halévy.

In a competing left-wing declaration published a week after this letter (“Fière déclaration d’intellectuels,” L’Humanité, 26 June 1919), Romain Rolland urged intellectuals to abandon the nationalistic attitude that had prevailed during World War I, when many supported the idea of engaged art and literature that would aim to maintain patriotic union.

Here Proust reproaches Halévy for being a signatory of a manifesto that argues for a nationalization of literature. Proust believes it to be akin to (and just as objectionable in tone as) the anthem “Deutschland über alles,” [Germany above all], a symbol of excessive nationalism.

Proust condemns all ideological excesses, whether the militant anticlericalism of Flaubert’s Homais or the reactionary Catholic conformism of the “parti de l’Intelligence” manifesto. He reminds Halévy that the anti-Semitic positions defended by the likes of Maurras during the Dreyfus Affair had little to do with justice, and did not bring much honor to France. We see Proust’s reservations regarding affirmations of nationalism in literature and art, as these have led to anti-Semitism in the past. The letter shows how Proust was concerned about the persistence of French chauvinism after the Allied victory.

Proust and Halévy represent two opposite viewpoints for the post-World War I generation of French writers and critics: one defended a conception of the artistic or literary work as an end in itself, whereas the other argued for art in the service of the nation. Proust believed literature should be above political orientation and have no other objective than the pursuit of truth.

Works cited

Proust, Marcel. Correspondance. Ed. Philip Kolb. Paris: Plon (21 vols), 1970-1993.