Selected Letters at the University of Illinois

by François Proulx, Assistant Professor of French

This online exhibition is part of The Great War: Experiences, Representations, Effects, a campus-wide initiative marking the centenary of World War I. (Read more about this exhibition)

At the outbreak of World War I in the summer of 1914, Marcel Proust (1871-1922) was experiencing professional success and private heartbreak. Swann’s Way, the first volume of his novel In Search of Lost Time, had appeared in November 1913, to largely positive reviews. Prestigious publishers who had previously turned down the novel now approached Proust to acquire the rights to its remaining volumes. Yet Proust found himself unable to work following the death of his driver Alfred Agostinelli, a man he “really loved” and “adored.” Meanwhile, the European powers were marching toward war.

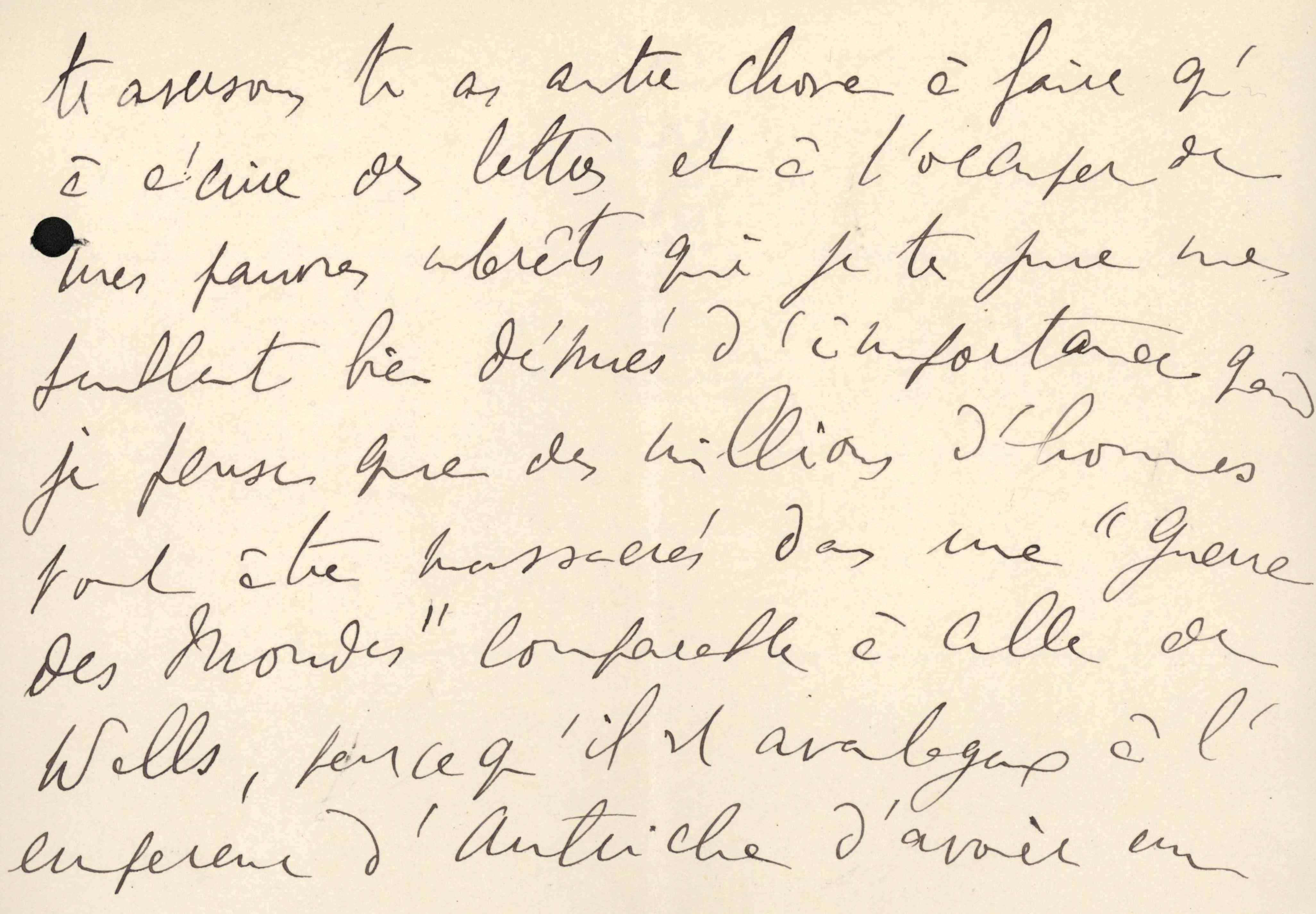

Letter from Marcel Proust to Lionel Hauser, 2 August 1914

In a letter to his financial advisor Lionel Hauser written the night of August 2, 19141 – mere hours before Germany formally declared war on France – Proust foresees the atrocities to come:

In the terrible days we are going through, you have other things to do besides writing letters and bothering with my petty interests, which I assure you seem wholly unimportant when I think that millions of men are going to be massacred in a War of the Worlds comparable with that of Wells,2 because the Emperor of Austria thinks it advantageous to have an outlet onto the Black Sea.3

He fears that one of these victims will be his younger brother, the doctor Robert Proust, who was mobilized on August 2 along with over three million Frenchmen:

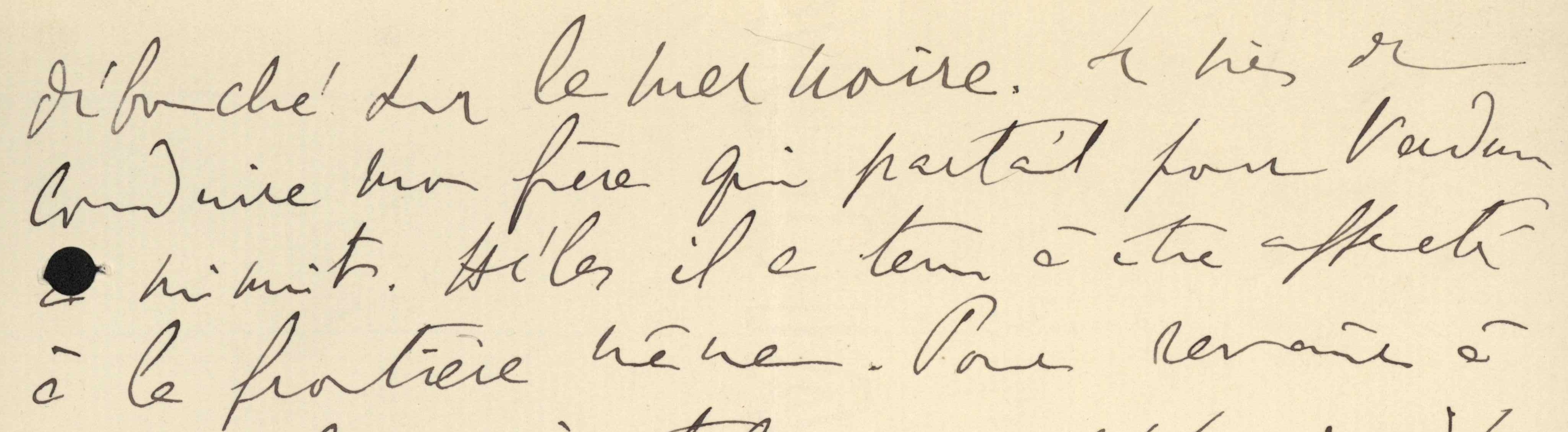

I have just seen off my brother who was leaving for Verdun at midnight. Alas he insisted on being posted to the actual border.

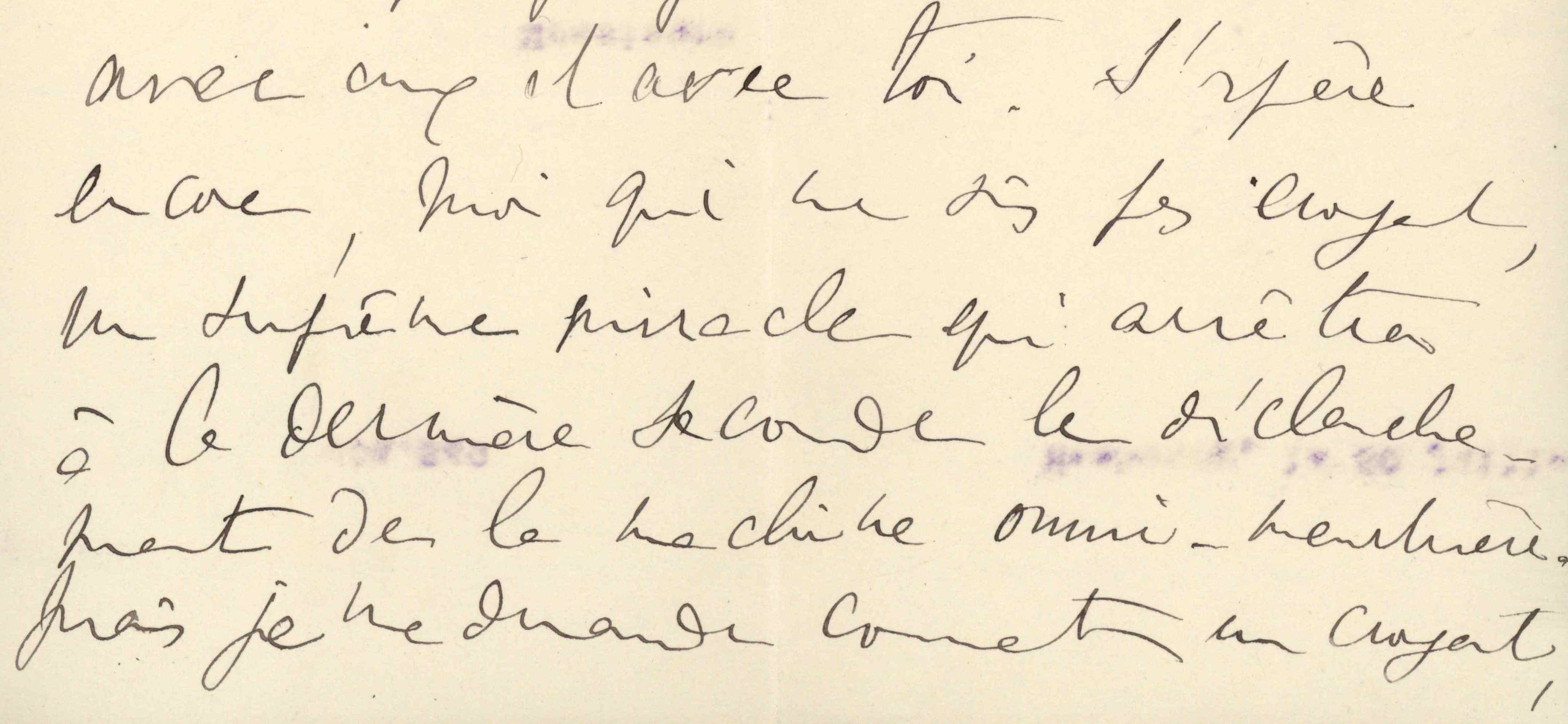

In closing, Proust reflects further on the impending war:

I still hope, non-believer though I am, that some supreme miracle will prevent, at the last second, the launch of the omni-murdering machine.

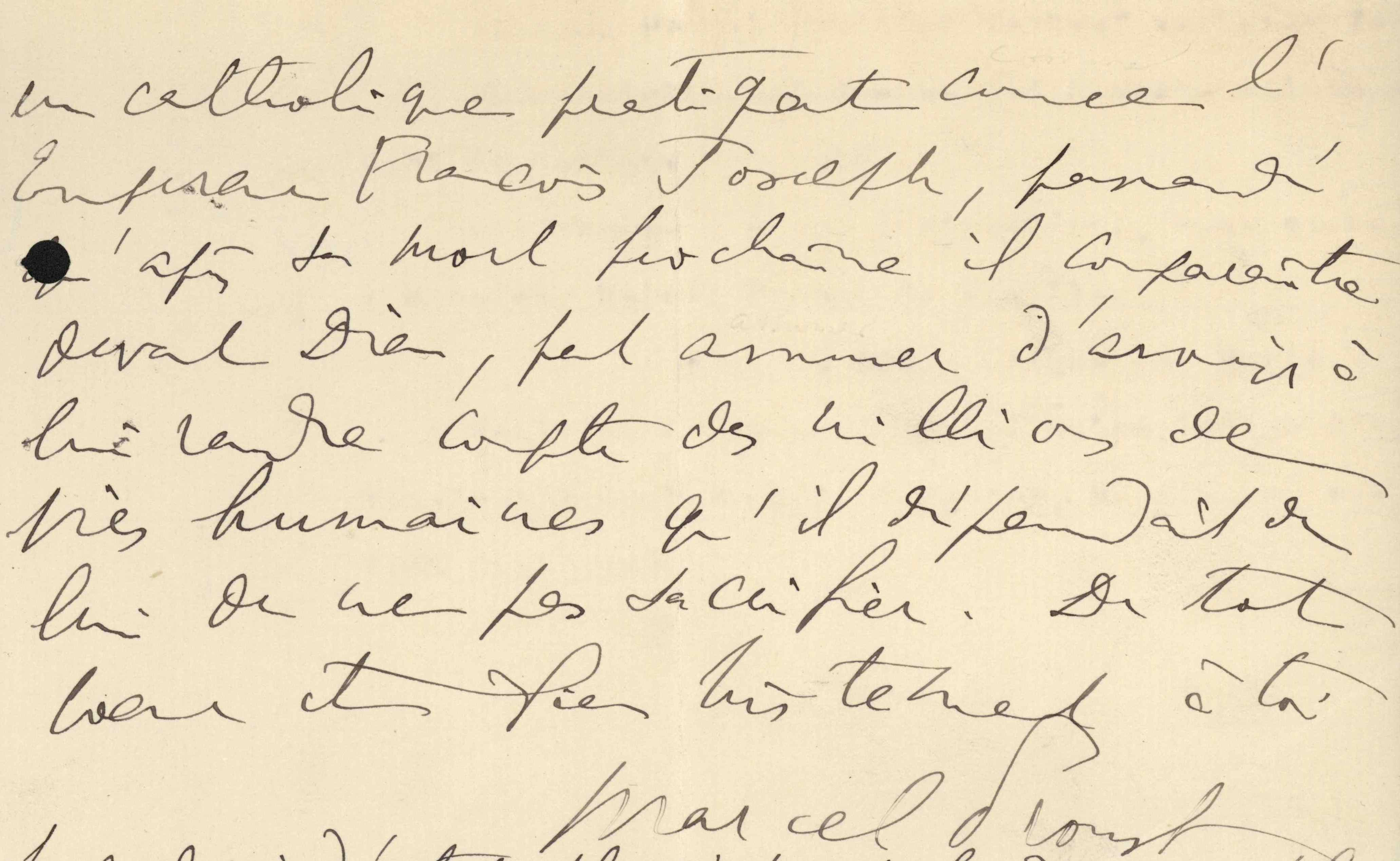

But I wonder how a believer, a practicing Catholic like the Emperor Franz Joseph, convinced that after his impending death he will appear before his God, can face having to account to him for the millions of human lives whose sacrifice it was in his power to prevent.

With all my heart and very sadly yours

Marcel Proust

Robert Proust survived the war, and was decorated for his courage in caring for the wounded under enemy fire. Marcel Proust left for the coastal town of Cabourg in September 1914, but soon returned to Paris where he remained for the duration of the war, enduring air raids and seeing the city’s social and cultural life first halted, then transformed. Due to his ill health, he was exempted from military duties, but many of his friends enrolled and fought, some never to return.

The war provided Proust with an unforeseen opportunity to greatly expand his novel: the three volumes announced when Swann’s Way appeared in 1913 had grown to five when In the Shadow of Young Girls In Flower appeared in 1919. After Marcel’s death in 1922, Robert Proust oversaw the publication of posthumous volumes until 1927, bringing the total number of volumes to seven. The final volume, Time Regained, includes many scenes set during and after the war, which Proust could not have imagined when he first conceived the novel in 1908.

This online exhibition was designed in collaboration with graduate students enrolled in the seminar “French 574: Marcel Proust.” Students have selected and commented on the following letters:

October 1914: Proust to Reynaldo Hahn, and March 1915: Reynaldo Hahn to Proust (by Anne-Bénédicte Guillaud-Marlieu)

March 1915: Proust to Louis d’Albufera (by Nick Strole)

April 1915: Madeleine Lemaire to Proust, and February 1918: Jacques-Émile Blanche to Proust (by Malyoune Benoit)

May 1915: Proust to Madame d’Humières (by Paola Pruneddu)

July 1915: Proust to Robert de Montesquiou, and Robert de Montesquiou to Proust (by Peter Tarjanyi)

July 1918: Proust to Louis Brun (by Laura Furrer)

The Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois houses over 1,100 letters to and from Marcel Proust, making it the largest collection of Proust’s letters in the world. This unique collection was built to support the remarkable work of Philip Kolb, who spent decades editing Proust’s vast correspondence. Today the collection continues to grow in collaboration with the Kolb-Proust Archive for Research: in 2013, sixteen new letters were acquired.

For those of us who do not understand French, to be able to “read” Proust’s letters is an incredible joy. The graduate students in “French 574: Marcel Proust,” Anne-Bénédicte Guillaud-Marlieu, Nick Strole, Malyoune Benoit, Paola Pruneddu, Peter Tarjanyi, and Laura Furrer, have given us these nuggets…and we are sincerely grateful.

And to complete the information and illustrate it, an unknown image of Marcel Proust in the war:

http://www.gerard-bertrand.net/PRO_guerre.html