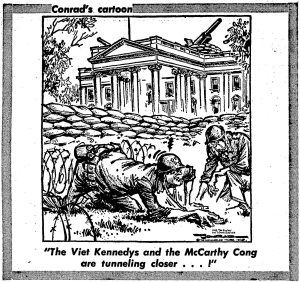

During the tumultuous years of the Depression, World War II, and the early Cold War, the University went through a roller-coaster ride of change: fluctuating enrollments and appropriations, liberal and conservative administrations.

The period began with President Harry Woodburn Chase offering a “new deal” to U of I students and faculty and ended with the untimely ouster of George Dinsmore Stoddard, another psychologist and another liberal. Stoddard had made strides toward awakening “the sleeping giant” that was the University of Illinois. It would be left to his successors to complete this task.

Further Resources

![]()

Administration

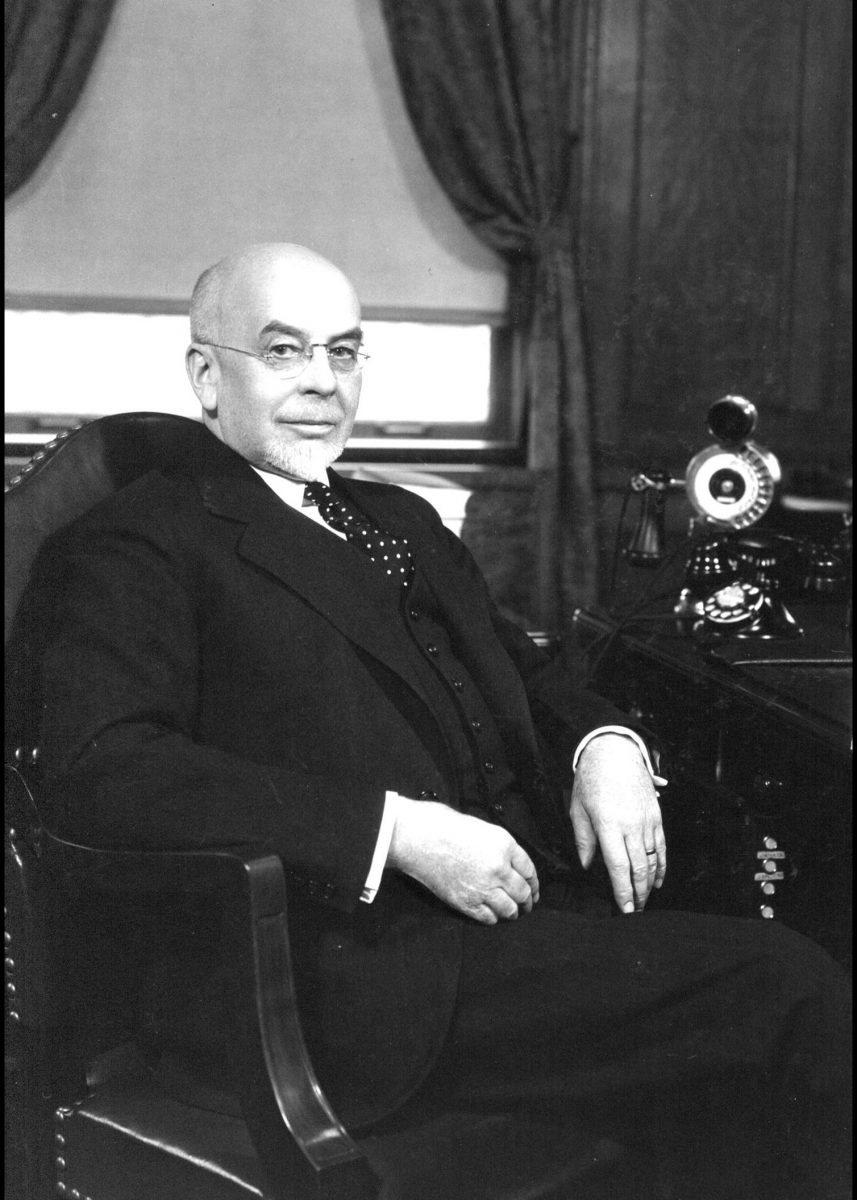

Arriving in 1930, President Harry Chase relaxed rigid student regulations and put faculty in charge of discipline. Unfortunately, the Depression almost immediately sank enrollment 12%, leading to large staff and salary cuts. Chase left in 1933. Successors Arthur Daniels and Arthur Willard also struggled with the Depression, but Willard secured federal funds to build multiple campus buildings including the Illini Union and Gregory Hall.

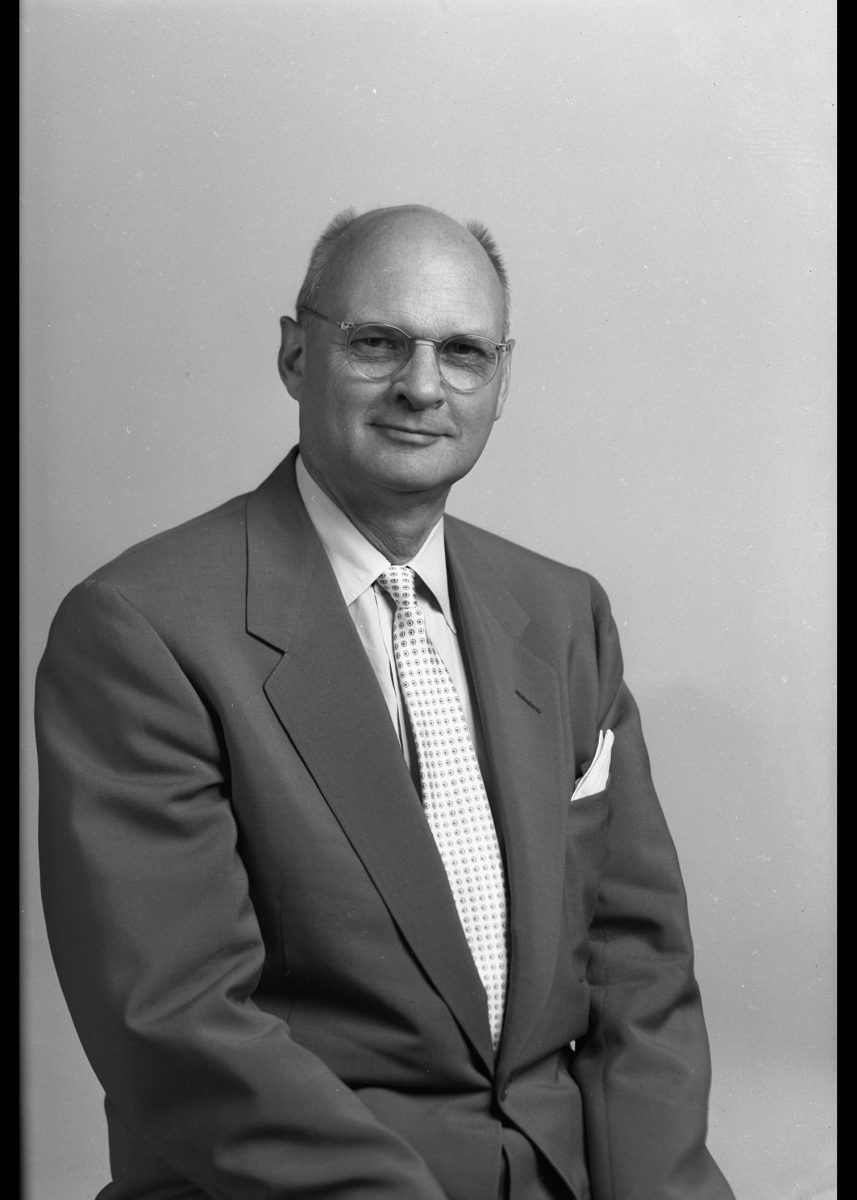

George Stoddard replaced Willard in 1946 and immediately began hiring top academics as faculty and administrators. The GI Bill swelled enrollment to nearly 20,000, necessitating new housing and two new university branches. Unfortunately, McCarthyism and local political spite led in 1953 to his ouster by the Board of Trustees in a midnight coup.

“Freedom from interferences with academic affairs is necessary to the maintenance of that spirit of critical inquiry which is essential in a great teaching and research institution.”

During the early 1930s, Harry Woodburn Chase, the former University of North Carolina president, led the U of I in new and exciting directions. Compared to the conservative Kinley, the progressive-minded Chase seemed like a breath of fresh air. Treating students as grown-ups, the new U of I president loosened student regulations and encouraged student initiative. Under Chase, the autocratic Council of Administration was scrapped and its powers given to the Faculty Senate. The Faculty now had charge of student discipline, with the deans of men and women assuming merely advisory roles. “There is no doubt but that President Chase, calling few if any people down or up, and ignoring fussy, fine-cut discipline, has by sheer force of personality brought about a new esprit de corps which has found its way to the furthermost points in the faculty, and on down into the student body,” the Illinois Alumni News declared.[1]

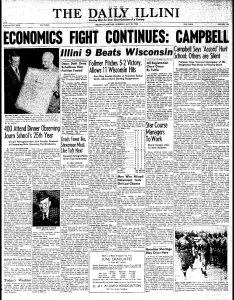

The Depression adversely affected University enrollment and finances. In 1930-31–Chase’s first year as president–the U of I’s Urbana-Champaign campus boasted a record enrollment of close to 11,000, and the University was enjoying the fruits of a record $12,114,902 appropriation, granted by the Legislature in 1929. According to historian Carl Stephens, “at probably no time in its history had the University stood higher in the general regard of the people of the state.”[2] And then the bottom dropped out as the Depression really took hold. Steep budget cuts were implemented, with staff salaries slashed between five and fifteen percent.[3] In the last year of the Chase administration (1932-33), Urbana-Champaign enrollment plummeted twelve percent, going from 10,525 to 9,263 students, and the numbers only began to rebound in 1934.[4] Appropriations dropped to $7,810,000 for the 1933-35 biennium and would not surpass the high water mark of 1929-31 until the end of the decade when an appropriation of slightly over $17 million was secured.[5]

Accepting a too-good-to-refuse offer to become New York University’s chancellor, Chase left the U of I in 1933 after only three years at the helm. His successors as president—Arthur Daniels and Arthur Willard—reigned in some of Chase’s reforms and returned conservative administration to the University. Accused of being a weak leader, Willard, a ventilation and heating engineer who had spent most of his time north of Green Street, struggled to cope with the effects of the Depression and World War II.[6] Handicapped by a lack of money, the Willard Administration nonetheless managed to cobble together—thanks in large part to federal money–a building program of note—one that included the Illini Union, Gregory Hall, and the Men’s Residence Hall, the first University men’s dormitory in well over fifty years.[7]

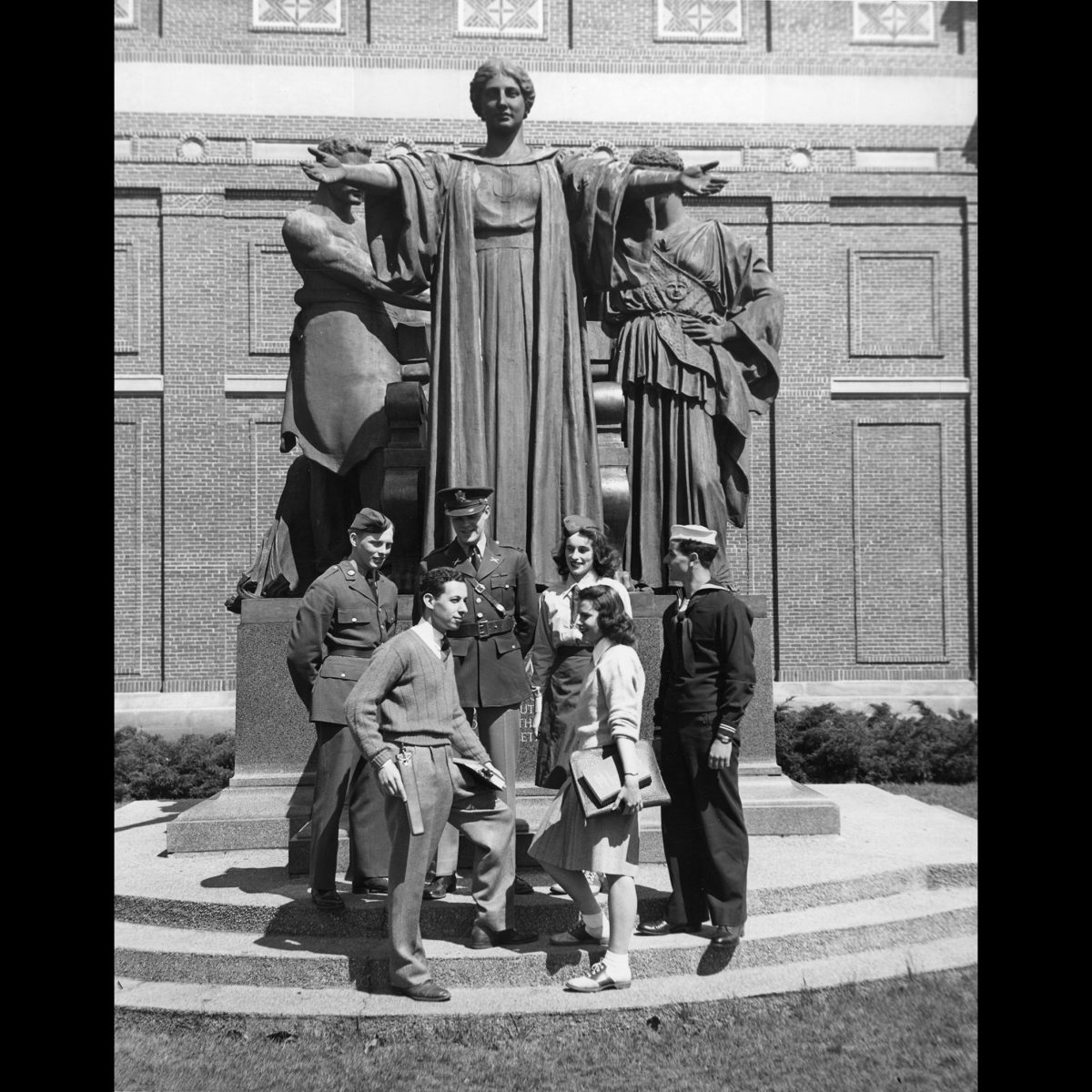

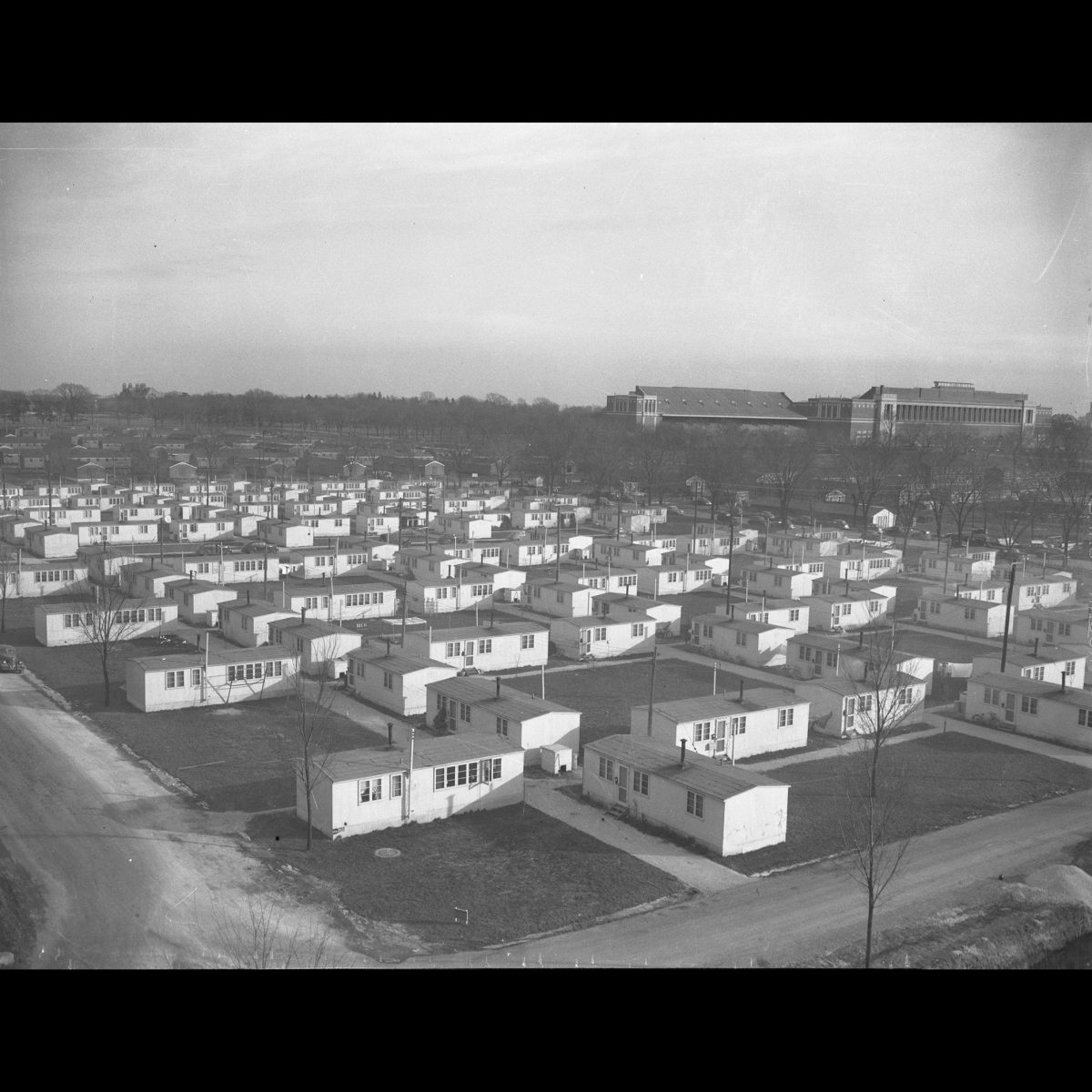

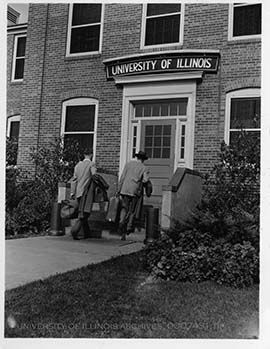

Following World War II, which saw a woman-majority campus for the first time, the University embarked upon an era of unprecedented growth.[8] Thanks to the GI Bill, thousands of veterans flocked to the University to receive the benefits of higher education, swelling enrollment to record levels approaching 20,000 students. University officials responded to the desperate need for housing by erecting temporary so-called “cardboard villages” around the campus: the Illini Village and Stadium Terrace complexes for 595 couples and the barracks-like Parade Ground Units for 1357 single students. In addition, two entire new University branches were opened within the space of a summer—one at Navy Pier in Chicago and the other at Galesburg, “The College Made in a Month.”[9]

Galesburg Campus

Taking over the reins of the University in September 1946, George Dinsmore Stoddard, a respected child psychologist, saw the U of I as “a sleeping giant” and he hoped to awaken it.[10] The liberal-minded Stoddard had grand plans for the University, and he began his tenure by filling the school’s top administrative spots with some of the best and the brightest in the academic world, many of whom were easterners.[11] His ambitions could be seen in the record-breaking $104 million budget he sought from the Legislature in 1947.[12] That year the University received from the Legislature a biennial appropriation of $61.5 million—short of Stoddard’s goal but nonetheless a record-breaking amount. Every one of Stoddard’s legislative campaigns would net record appropriations, culminating with an $82.5 million appropriation for the 1953-55 biennium.[13]

Stoddard acquired many enemies during his seven years as U of I president. Conservatives deplored his liberal views and believed that he was “soft on Communism.” Isolationists detested his internationalism. High-ranking figures in the Catholic Church hierarchy scored him as an atheist.[14] Many local townspeople viewed him as an outsider who was making unnecessary waves, especially in racial matters.[15] And then there was The News-Gazette. “Everybody in this community knows that this controversy has been kept alive by a single newspaper, namely, The Champaign-Urbana News Gazette,” Stoddard told a reporter for the Christian Science Monitor, “and that this newspaper has been guilty so frequently of misstatement and distortion that most of us have stopped even trying to ‘correct the record.’”[16] Perhaps most damagingly, Stoddard had recently halted all University experiments on a purported cancer cure called Krebiozen; this decision angered certain powerful politicians who had a financial stake in the drug.[17]

The opposition to Stoddard came to a head in July 1953. During a midnight meeting on July 23rd, the Board of Trustees voted to oust Stoddard as president. Park Livingston, the Board president, had engineered “the coup,” and he was aided and abetted by Harold “Red” Grange—a trustee since 1951. In The News-Gazette’s words, Grange had called the play, making the motion that led to Stoddard’s ouster.[18] The news of the U of I president’s firing reverberated throughout the academic world and beyond and would have lasting repercussions. “The administration of President Stoddard has brought to Illinois a genuine stature which recalls the distinction which it attained in the time of President James,” an alumnus declared in a letter to Wayne Johnston, one of only three trustees to vote for Stoddard on that fateful July night. “The full price Illinois will have to pay for parting with the services of such a man will be a heavy one, and only liquidated after a long term of years.[19]“

References

[1] Illinois Alumni News, February 1933.

[2] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 11, 9, University of Illinois Archives.

[3] Ibid., 10.

[4] Daily Illini, 25 September 1932; Stephens, Chapter 11, 17.

[5] Ibid., Chapter 11, 10; Daily Illini, 29 June 1939.

[6] Ibid., 18 October 1942.

[7] Stephens, Chapter 11, 24.

[8] Roger Ebert, An Illini Century: One Hundred Years of Campus Life (Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1967), 148.

[9] Carl Stephens, Illini Years (Urbana: University of Illinois Press), 113.

[10] Winton Solberg and Robert Tomilson, “Academic McCarthyism and Keynesian Economics: The Bowen Controversy at the University of Illinois, History of Political Economy 29:1 (1997), 56-57.

[11] Stephens, Illini Years, 114.

[12] Daily Illini, 23 October 1946.

[13] George Stoddard, “Notes for a Seven-Year Report of the President of the University of Illinois, 1946-1953,” School and Society 78 (28 November 1953), 167.

[14] Solberg and Tomilson, 80.

[15] Daily Illini, 28 July 1953.

[16] George Stoddard to Godfrey Sperling, 18 August 1953, Coleman Griffith Papers (5/1/21), B: 2, F: Correspondence, A-Z, July-November 1953, University of Illinois Archives.

[17] Solberg and Tomilson, 80.

[18] Champaign-Urbana News-Gazette, 25 July 1953.

[19] Gerald Carson to Wayne Johnston, 1 September 1953, Wayne Johnston Papers (1/20/3), B: 6, F: 119-10- 2, University of Illinois Archives.

Further Resources – Presidents’ Papers

![]()

Academics

By 1930, too much red tape caused the University to fall behind its peers. New President Harry Chase (1930-33) gave faculty more independence, but his two successors (Arthur Daniels, Arthur Willard) largely maintained the status quo. In 1946, George Stoddard, a former New York education commissioner, was hired to change that trajectory. He created seven new institutes and curricula, and supported creation of public WILL-TV. Newly invigorated faculty created the fastest betatron machine, the ILLIAC-1 computer, and grew the Library to over 2 million books.

McCarthyism, however, created problems, particularly against Keynsian economist Howard Bowen, dean of the commerce college. Despite Stoddard’s support, he was forced to resign. Politics eventually claimed Stoddard himself.

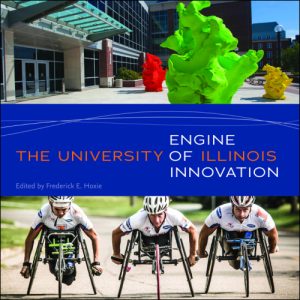

“By the turn of the twentieth century, it was clear that the University of Illinois would be an engine of innovation, a place where faculty, students, and campus leaders would stimulate and nurture new ideas that could change the world.”

Before accepting the U of I presidency, Harry Woodburn Chase asked “a good many people in the educational world” what they thought of the school. What he heard was not encouraging. “There was a general agreement that the University of Illinois was an institution of fine possibilities which somehow had failed to realize those possibilities to the extent which was anticipated ten or fifteen years ago,” Chase later told Kendric Babcock, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. Chase said that, in educational circles, Illinois was not considered to be on the same level as California, Minnesota, and Michigan. The big problem at Illinois, according to Chase, was “the entanglement of the University in red tape and restrictive regulations in both its faculty and its student activities.” The U of I, Chase declared, was “slowly strangling to death” on its own red tape.[1]

Franklin Allen (1914-2005) was a member of the Class of 1937. He joined the Farmhouse fraternity and was the Senior Editor of the Illinois Agriculturalist. Franklin felt the strain of the Great Depression during college, and he took time off from college and held jobs to cover expenses. However, he thought he had good luck in life. Voices of Illinois interview

Chase’s liberalizing reforms gave more authority and independence to the faculty.[2] After only three years in office, Chase left the U of I to become the chancellor of New York University. Chase’s successors, Arthur Daniels and Arthur Willard, largely preserved the status quo on the academic front during turbulent years of depression, war, and up-and-down enrollment. Responding to the claim made in the early 1940s that “the University has been on the downgrade since 1934,” the Board of Trustees hired the American Council on Education (ACE) to examine the state of the U of I’s educational program. The findings were troubling. “It (the University) has failed to advance during this period at points where other similar institutions have pressed forward significantly toward improvement,” the ACE commission concluded in 1943.[3]

Succeeding Willard in September 1946, the 48-year-old George Dinsmore Stoddard, a respected child psychologist and the former commissioner of education of the University of the State of New York, breathed new life into the University. The liberal-minded Stoddard had grand plans for the University, and he began his tenure by filling the school’s top administrative spots with some of the best and the brightest in the academic world, many of whom were easterners. His ambitions could be seen in the record-breaking $104 million budget he sought from the Legislature in 1947. Borrowing the words of another university president, Stoddard saw the U of I as “a sleeping giant which is awakening.”[4]

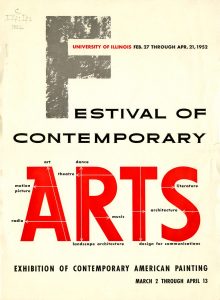

Stoddard served only seven years as president, his tenure cut short by political machinations. Stoddard’s administration, though, had accomplished much academically in a brief amount of time. Under Stoddard, various institutes were developed: the Institute of Government and Public Affairs, the Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations, the Institute of Communications Research, and the Institute for Research on Exceptional Children; the Graduate School of Business Administration, a family and community life curriculum, and the full curriculum in veterinary medicine were launched. On the cultural front, Stoddard strongly supported the Festival of Contemporary Arts (which brought to the University such luminaries as Martha Graham, Carl Sandburg, Aaron Copland, Igor Stravinsky, Langston Hughes, and Leopold Stokowski) as well as public television; his intense lobbying in behalf of what would become WILL-TV incurred the wrath of conservative politicians and the powerful Illinois Broadcasters Association.

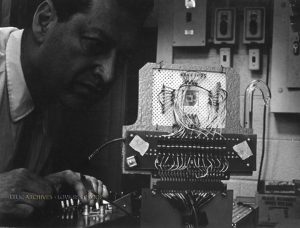

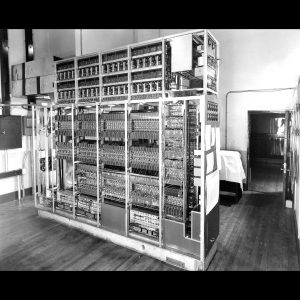

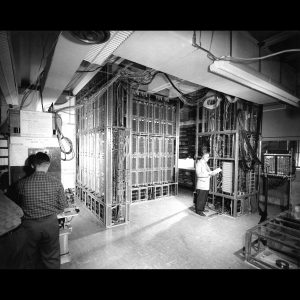

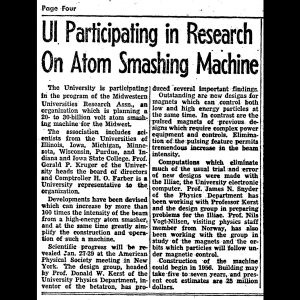

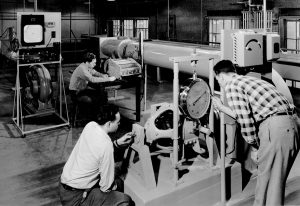

Research in the Stoddard Administration

Buoyed by a total of $17.6 million in federal government contracts, University research flourished during the Stoddard era.[5] Building upon his work of the early 1940s, physicist Donald Kerst constructed ever-bigger betatrons that accelerated electrons at ever-greater speeds. [6] Illinois researchers also developed two pioneer supercomputers: ORDVAC and ILLIAC I. Built for the Ballistics Research Laboratory at the Aberdeen Proving Ground, ORDVAC contained 2178 vacuum tubes, had a main memory consisting of 1024 words of 40 bits each, and was one of the first computers to be used remotely.[7] A twin of ORDVAC, ILLIAC I was the first computer with so-called von Neumann architecture (a kind of computer design described by the mathematician and physicist John von Neumann in 1945) to be owned by an American university.[8]

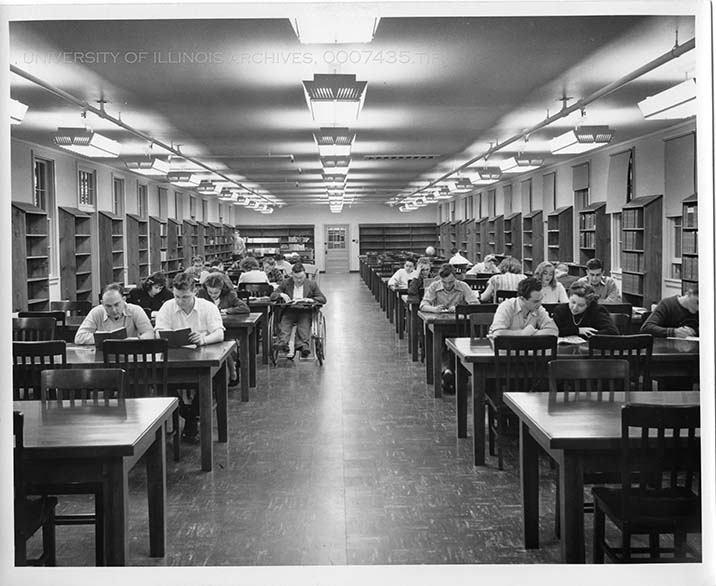

Stoddard seemed to be particularly proud of the advances made by the University Library during his administration. The Library had already grown by leaps and bounds under Phineas Windsor, Library director from 1909 to 1940. Windsor oversaw the Library’s rise from being the twelfth to the fifth largest American university library, and he was at the helm in 1935 when it finally realized Edmund James’ goal of a million books.[9] Robert Downs, who became Library director in 1943, kicked things up a notch. During the seven years of the Stoddard administration, the Library, with Downs in charge, acquired 653,000 volumes, bringing its total holdings to 2,656,000 volumes. This average annual growth of 93,000 volumes was exceeded by only Harvard and Yale. The Library also obtained some notable collections, including the Ernest Ingold collection of Shakespeare folios, and expanded its public outreach, even producing a radio program: “Library Presents.” Library usage grew to record levels; an average of 1,160,000 volumes were loaned per year in this seven-year period.[10]

During the Cold War, academia became a political battlefield pitting the right against the left. Academic McCarthyism was the order of the day. Taking a page out of the playbook of Senator Joseph McCarthy, the anti-Communist demagogue, local State Representative Ora Dillavou claimed in 1950 that there were “fifty reds, pinks, and socialists” on the University faculty. A Cold War liberal opposed to both Communism and McCarthyism, Stoddard scoffed at this assertion.[11] During his tenure, he defended many of his faculty against accusations that they were “subversive.” The U of I president, for instance, backed a socialist professor in the Institute of Industrial and Labor Relations even after legislators threatened to cut the institute’s appropriation. Stoddard believed that the democratic system allowed “peaceful efforts in support of socialism.”[12]

Nonetheless, under Stoddard, several academics, including Alejandro Dagoberto Marroquin, a visiting Spanish professor, and Frank Kornacker, an Architecture professor, lost their jobs after being subjected to Security Office background checks.[13] And other professors came under suspicion. For example, in January 1950, Dean of Students Fred Turner asked Security Officer Joseph Ewers whether Natalia Belting, a History associate professor, had any connection with the leftist Student-Community Interracial Committee. (Mrs. Dillavou, wife of the staunchly anti-Communist legislator, had prompted Turner’s query; she wanted to know whether Belting deserved to have a seat on the YWCA board, which was then embroiled in “an extensive row . . . over racial questions.”)[14] After consulting his files and quizzing informants, Ewers could not find any evidence that Belting had ever taken any “active interest” in civil rights movements and cited her involvement with a local sorority as a factor in her favor. “Miss Belting is currently chairman of the Advisory Board of Delta Zeta sorority on this campus, which fact, although not conclusive, indicates that she is a person cognizant of complications which might possibly arise in situations of mixed social groups,” Ewers wrote.[15]

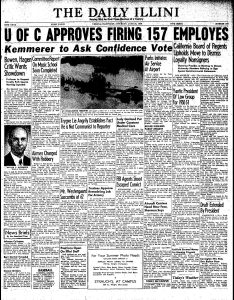

The most famous academic wrangle of the Stoddard era was the so-called “Bowen controversy.” Appointed by Stoddard to head the College of Commerce in 1947, Howard Bowen, an East Coast economist, soon ran afoul of some of his more conservative colleagues. Among other things, the conservatives did not appreciate the fact that Bowen was a Keynesian economist and that he preferred to hire easterners.[16] According to Nicholas Wisseman, the struggle “had much more to do with old guard versus new guard hostility in the Economics Department than certifiable McCarthyism in action.”[17] The dispute blew up into a headline-making affair, and the conservatives ultimately prevailed, with Bowen resigning as dean. Stoddard had supported Bowen almost until the end.[18] The Bowen controversy set the stage for future political meddling that would ultimately claim Stoddard himself as a victim.

References

[1] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 11, 3-4, University of Illinois Archives.

[2] Ibid., 9.

[3] Commission of the American Council on Education, University of Illinois Survey Report, Washington, D.C., 1943, 19.

[4] Winton Solberg and Robert Tomilson, “Academic McCarthyism and Keynesian Economics: The Bowen Controversy at the University of Illinois, History of Political Economy 29:1 (1997), 56-57.

[5] George Stoddard, “Notes for a Seven-Year Report of the President of the University of Illinois, 1946-1953,” School and Society 78 (28 November 1953), 166-68.

[6] Bethany Anderson, “’A Very Bold and Original Device’: Donald Kerst and the Betatron,” University of Illinois Archives Blog, online at http://archives.library.illinois.edu/blog/donald-kerst-and-the-betatron/

[7] “The Computer from Pascal to von Neumann – Chapter 6, by Herman H. Goldstine”. Princeton University Press. 1972. ISBN 0-691-08104-2.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Stephens, Chapter 13, 39-40.

[10] Stoddard, 168.

[11] Nicholas Wisseman, “Falsely Accused: Cold War Liberalism Reassessed,” The Historian 66 (June 2004), 329.

[12] Ibid., 332.

[13] Ibid., 327-28.

[14] Turner to Ewers, 20 January 1950, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 11, F: Ewers, University of Illinois Archives.

[15] Ewers to Turner, 26 January 1950, ibid.

[16] Solberg and Tomilson, 61-63.

[17] Wisseman, 332-33.

[18] Ibid.

Further Resources

![]()

Campus Architecture & Planning

Funds for new construction dwindled to merely $50,000 during the early 1930s until, in 1937, a ceiling collapsed in University Hall. Gov. Horner, a foe of construction, then released funds to help build its replacement, Gregory Hall.

University Hall’s demise opened space for the new Illini Union, financed through the New Deal and a loan. Construction of the Natural Resources Building and Men’s Residence Hall soon followed, plus additions to the Library and McKinley Hospital.

After a moratorium during the war, building began again in the late 1940s. Aside from the “carboard villages” erected for returning GIs, new buildings included Lincoln Avenue Residence Hall, and the Veterinary Medicine, Electrical Engineering, Chemical Engineering, and Mechanical Engineering buildings.

Aerial Panoramas of Campus from the Louis and Ruth Wright Papers, 1934-35

University Hall (1871-1938) Fly Through Animation

Willard Building Project

From the Building Program Committee Subject File

The Rise and Fall of the University Hall

During the first eight years of the Depression, the University received a total of only $50,000 from the Legislature for new construction compared to the over ten million dollars obtained for buildings in the 1920s. A collapse of a ceiling in University Hall —the school’s oldest and still most heavily used classroom building—suddenly changed things. Just before one in the afternoon on a drizzly and unseasonably mild day in January 1938, roughly a ton of plaster and metal lathing gave way from the ceiling and crashed onto the floor in Room 315. Fortunately there were no students in the classroom at the time. The 25-by-20-foot chunk of ceiling had fallen with enough force to knock the writing arms off many of the lecture chairs, leaving behind only stumps. The Board of Trustees quickly ordered University Hall to be dismantled, and the dilapidated Second Empire structure that had long been the bane of campus planners finally met its end.[1] President Arthur Willard, a man who wanted to be known as a builder, bitterly referred to himself as a “razer” of buildings.[2]

During a visit to the University the following March, Governor Henry Horner indicated his full support for a new building to replace University Hall. Horner had long opposed the University’s major building requests; fighting the Depression had been his top priority—his administration was paying out three million dollars a month in relief to the unemployed. “Gov. Horner has been the greatest obstacle to a resumption of the University building program,” the Daily Illini editorialized. “Now that he has changed his mind, the road is clear—at least as far as the replacement of University Hall is concerned.”[3] True to his word, Horner helped secure a $700,000 appropriation for the new classroom building—the future Gregory Hall.[4]

The removal of University Hall also opened up a prime spot for the long-desired Illini Union Building at “the front door of the campus.” Since early in 1937, two committees had debated where to put the student center, with one ultimately suggesting a site on the Morrow Plots and the other a spot at the northwest corner of Daniel and Wright streets (the current location of the Illinois Union Bookstore).[5] The question was revisited after the demise of University Hall, and in July 1938 a site for the Illini Union was chosen on “the center axis of the central quadrangle, south of Green Street, between the Natural History Building and the Law Building (Altgeld Hall).”[6] By then, the University finally had found a way to finance the Union building, coupling a $450,000 grant from the New Deal’s Public Works Administration with a $550,000 loan from the Connecticut Mutual Life Insurance Company.[7]

In the late 1930s, President Willard suddenly had a building program worth bragging about. Gregory Hall—the first air-conditioned structure on campus—and the Illini Union were only a part of the story. New additions to the Library and McKinley Hospital were also going up, and on the south campus, the State of Illinois’ Natural Resources Building was beginning to take shape. This last structure would provide much-needed space for the state geological and natural history surveys, then scattered across campus in several buildings. The project took a long time to get off the ground, with the State and the University wrangling over the building’s location and over who was responsible for its design.[8] These new buildings would soon be joined by two more: Abbott Power Plant, looming on the western edge of campus, and the Men’s Residence Hall.

Backed by an organization of independent men, University officials had braved the wrath of fraternities and boarding house operators and pushed for a men’s residence hall. The effort succeeded, and the first University men’s dormitory in decades was constructed on the Parade Ground just west of Huff Gym. The so-called Triad, consisting of three four-story colonial-style buildings (later named Clark, Lundgren, and Barton halls), opened its doors to 364 male students in September 1941. The Daily Illini welcomed the new residence hall, calling it “a practical advance toward solution of the vexatious independent housing problem.”[9]

During World War II, campus construction ground to a halt. As the conflict drew to a close, University officials began planning for the expected post-war enrollment boom. In the summer of 1944, the University’s Building Program Committee submitted a $32 million building wish list to the Board of Trustees.[10] Reflecting the high hopes of U of I administrators in the heady final year of the war, a 1944 campus plan showed dozens of new structures, including buildings for electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, chemical engineering, home economics, animal husbandry, and physical education.

These new buildings would be needed more than ever; in the fall of 1946, the University’s Urbana campus registered an enrollment of 18,378—far and away the school’s largest enrollment up to that point.[11] A large majority of these students were veterans returning on the GI Bill. Where to house all of these new students, some twenty percent of whom were married? The University responded by erecting temporary “cardboard villages” around the campus: the Illini Village and Stadium Terrace complexes for 595 couples and the barracks-like Parade Ground Units for 1,357 single students. In addition, two entire new University branches were opened within the space of a summer—one at Navy Pier in Chicago and the other at Galesburg, “The College Made in a Month.”

Utility took a back seat to beauty in the post-war period. Nonetheless, President Willard objected to the designs of the Chemical Engineering, Electrical Engineering, and Mechanical Engineering buildings. The planned structures were modular, streamlined, and unornamented—in other words, modern. Willard was a fan of old-school architecture. He, after all, had endorsed the colonial revival design of the Illini Union because it made the building, in his view, look “old and traditional, even more so than Uni. Hall ever did.” Willard could not stomach the new designs and suggested that they might need to be changed.

George Dinsmore Stoddard, the University’s new president, responded to such criticism by creating a committee to advise on architectural design. The so-called Consultative Committee on Architecture had three traditional architects and one wildcard in the deck—Eliel Saarinen, the progressive, internationally known Finnish architect. The independent-minded Saarinen only reluctantly agreed to serve on Stoddard’s committee; he was wary of what he termed the U of I School of Architecture’s “stylistic tradition.” “And ‘stylistic tradition’, imitative in spirit as it is, is an approach to architecture with which I never have been able to cooperate,” Saarinen explained to Stoddard.[12]

It quickly became evident that the three traditionalists on the committee strongly favored Georgian architecture. On April 19, 1947, the trio sent a telegram to President Stoddard calling for all new buildings to be designed “in Georgian character.” Stoddard was, in his own words, “astonished” by the tone of the telegram. Torpedoed by the telegram, the committee died an early death. The traditionalists had hoped to impose Georgian architecture on the campus, but instead they, ironically, opened the door to modernism.

President Stoddard came to believe that “neither duplication and imitation, on the one hand, or ‘modernization’ on the other” was the answer. The old and the new had to be wedded somehow, he believed. This marriage of the past and the present would turn out to be a hallmark of the Stoddard presidency’s building program, from the modern-Georgian Lincoln Avenue Residence Hall (1949) and Veterinary Medicine Building (1952) to the even more modern-Georgian Electrical Engineering Building (1949) and Chemical Engineering Building (1950) to the starkly modern Mechanical Engineering Building (1949), Student-Staff Apartments (1950), and Animal Sciences Laboratory (1952).

References

Information for this unit came from Lex Tate and John Franch, An Illini Place: The Campus of the University of Illinois (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, forthcoming).

[1] Board of Trustees Minutes, January 20, 1938.

[2] Janata to Brichford, 24 July 1967, Maynord Brichford Papers (35/3/150), University of Illinois Archives.

[3] Daily Illini, 12 March 1938.

[4] Daily Illini, 18 May 1938.

[5] Daily Illini, 23 June 1938.

[6] Board of Trustees Minutes, July 15, 1940.

[7] Open House Brochure, Illini Union File (2/9/809), University of Illinois Archives.

[8] Daily Illini, 20 January 1938.

[9] Daily Illini, 17 November 1939.

[10] Building Program Committee Publications, 1937-current, (4/6/806) B:1, University of Illinois Archives.

[11] “Comparative Summary of Students: Years 1946-47 and 1947-48”, Office of Admissions and Records, Enrollment Tables (25/3/810), University of Illinois Archives.

[12] Saarinen to Stoddard, date, George D. Stoddard General Correspondence (2/10/1), B:23, University of Illinois Archives.

Further Resources

Diversity

Enrollment plummeted during the Depression and World War II, particularly for foreign and African American students. From a high of 151 in 1929, foreign enrollment dropped to only 57 by 1946 before climbing to 570 in 1954. And while the GI Bill swelled the numbers of Americans enrolling at the U of I, African American enrollment dropped from 138 in 1929 to only 55 in 1953.

As early as the mid-1930s, however, African Americans actively fought discrimination in housing and restaurants, including a successful three month picketing campaign in 1946. Jewish students also faced discrimination from local landlords, with the newish West Hall (now Evans Hall) almost their only option. This apparently made the non-Jewish residents want to move, according to the head of the Physical Plant department.

Between the years 1930 and 1953, University enrollment experienced peaks and valleys. The number of students plummeted in the early Depression years, then rebounded beginning in 1934, fell during World War II to levels not seen since the 1910s, and, finally, in the post-war period, reached unprecedented heights thanks to the GI Bill and the influx of veterans it made possible. The GI Bill democratized higher education, shattering the notion that college was the exclusive preserve of the middle and upper classes. Yet African American enrollment showed a marked fall-off during this period, dropping from 138 students in 1929-30 to 55 in 1953-54.[1]

During the Depression and World War II years, the number of international students at the U of I declined precipitously. In 1928-1929 there were 151 international students at the University; by 1946, the number had dropped to 57.[2] After the war, the international student population recovered in a big way, reaching 570 in 1954, with 65 nations represented.[3] With its xenophobia and repression, the post-war years were a difficult time for many students from other nations. Fortunately, they had a strong advocate in the form of Arthur Hamilton, the assistant dean of foreign students. “If you are a student in trouble of any sort, you see Dr. Hamilton,” a Chinese student wrote in 1954. “When you are fasting because you are out of money, he either helps you to find a job or to arrange a temporary loan. When you are put on the spot by an immigration officer, you ask him to call Washington. When you are depressed because you are lonely and blue in an unfamiliar country, you talk with him and he will make you feel like going to a football game again.”[4]

The Depression was a time of heightened political activity in Urbana-Champaign as elsewhere. In the mid-1930s African Americans and their white allies launched a vigorous drive to combat local discrimination in its many forms. After Boyd’s Cafe—the only campus restaurant (except for the University cafeteria) serving African Americans—closed, Alpha Phi Alpha and Kappa Alpha Psi, African American fraternities, opened a short-lived cooperative restaurant in the spring of 1936.[5] Dean of Men Fred Turner had deemed the restaurant to be “a dangerous venture.” “I think that the social implications which arise from the mixed white and colored establishment located in a building used partially as a dormitory . . . are such that we should seriously consider doing something to prevent this cooperative from gaining much of a foothold” Turner wrote to President Willard. Turner proposed that the University itself operate a cafeteria open to everyone regardless of race.[6]

Directly challenging this restaurant discrimination, small groups of African American and white students entered campus eateries in the fall of 1937 and asked to be served. The resulting service at the Ford Hopkins store on campus included such “unpleasantries” as fingers being poked into food and food being seasoned with too much salt and pepper. According to Dean Turner, in at least one instance milk was spiked with large amounts of Milk of Magnesia and traces of phenol, an extremely poisonous compound.[7] Overt discrimination by campus eateries finally came to an end after World War II thanks to the efforts of a multiracial group of students, faculty, and community members—the Student-Community Interracial Committee. After a three month picketing campaign waged by the Committee in the spring and summer of 1946, six hold-out restaurants (including the Campus Steak ‘n Shake and Bidwell’s Confectionery) finally agreed to sign a non-discrimination pledge.[8]

African Americans also achieved progress in the fight against housing discrimination. Barred from most boardinghouses, African Americans had two rooming options in the 1930s: live in the private residences of local black families, often quite far from campus, or join a sorority or fraternity. In the 1930s, two African American organizations—the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority and Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity—owned houses that accommodated large numbers of African American students. During the 1938-39 school year, fourteen of the 36 African American women at the University lived in the Alpha Kappa Alpha house at 1201 West Stoughton Street in Urbana, while 24 of the school’s 65 African American men resided in the Kappa Alpha Psi house at 707 South Third Street.[9]

The University had taken an unofficial interest in helping these African American organizations acquire their homes. (However, Assistant Dean of Men Charles R. Frederick had expressed concern over Kappa Alpha Psi’s move into the heart of the fraternity district, fearing that white “fraternities will eventually create an incident in their efforts to harass the negro group.”)[10] But, a few years before, University officials had thwarted an attempt by an African American fraternity—probably Kappa Alpha Psi—to purchase a home at 1206 West Springfield Avenue. Charles Havens, the Physical Plant director, advised that the University itself purchase this property, located near an African American rooming house and the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, in order to deny it to the fraternity. “You can readily understand that if four houses out of five in a block are owned by negroes, it will unquestionably lower the value of real estate in this section and in lowering the value will, therefore, attract other colored people and make it possible for them to expand into adjacent blocks,” Havens wrote to two trustees. “Such a development will not improve our campus.” According to Havens, Dean of Women Maria Leonard believed that the University could not continue operating its two women’s cooperative houses in the area if the African American fraternity moved into the immediate neighborhood.[11] On September 30, 1936, the Board of Trustees authorized the University’s purchase of the Springfield Avenue property.[12]

The Women’s Residence Halls were theoretically open to African American students, according to Albert Lee, the unofficial dean of African American students, but in practice they were not.[13] The Wesley Foundation-sponsored Wescoga women’s cooperative house paved the way for desegregated housing in the summer of 1945 when it welcomed an African American as a member.[14] Pressured by Charles Jenkins, an African American lawyer and state representative, President Arthur Willard eventually agreed to reserve one room in the Women’s Residence Halls for African American students. On August 11, 1945, Quintella King and Ruthe Cash were chosen to be the first African Americans to reside in a U of I dormitory.[15] In September 1946, newly elected UI President George Stoddard declared that the University had a responsibility to house racial minorities. This is “more than a pious gesture,” Stoddard told the Board of Trustees, “. . . it is a statement and clarification of university policy.”[16]

Jewish students also faced continuing housing discrimination, with many local landlords refusing to rent to them. Early in 1934, a Jewish woman wrote to the Daily Illini complaining of this “social ostracism.” “Because Moses brought down the Ten Commandments, Jewish students can’t be admitted to the better houses on campus,” she lamented.[17] With few other options in terms of housing, Jewish women started flocking to West Hall (later Evans Hall) shortly after it was completed in 1925. Reporting to President Willard in 1936, Charles Havens, of the Physical Plant Department, claimed that the “Jewish girls refuse to live anywhere except in West Hall when they learn that there are more Jewish girls there than in any of the other units.” Havens continued: “The problem has been in evidence for the past few years and has in most cases been settled by giving the girls their choice sooner or later. With as large a percentage of Jewish girls in West Hall, the Gentile girls are anxious to move to the other hall.”[18]

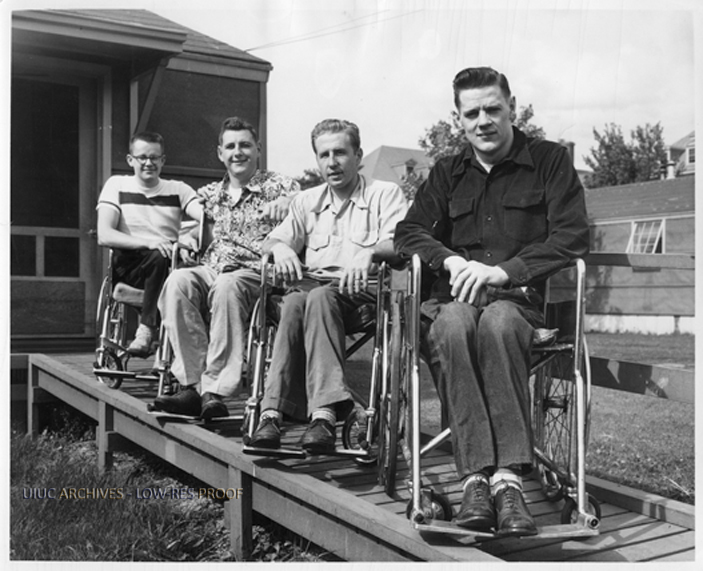

Many physically challenged students found the University to be a welcoming place in the post-war years, thanks in no small part to Timothy Nugent, head of the school’s Special Rehabilitation program and later the Division of Rehabilitation-Education Services (DRES). Begun in 1948 at the University’s short-lived Galesburg campus, the Special Education program—one of the first of its kind in the nation—taught physically challenged students to, in Nugent’s words, “live happily and securely in a wheelchair” through the use of corrective therapy, functional training, counseling, and sports. After the closing of the Galesburg campus in the spring of 1949, the program was transferred along with Nugent to Urbana-Champaign.[19] To accommodate the fourteen physically challenged students coming from Galesburg, the University installed wheelchair ramps at several housing units on the Parade Ground and at Lincoln Hall, Gregory Hall, and the Library.[20] During the first fifteen years of its existence, Nugent’s Division of Rehabilitation Education Services (DRES) was housed on the Parade Ground in a U. S. Army surplus barracks.[21]

Timothy Nugent became a legend in his own time. “I realize that, this late in his life, it is unlikely that Mr. Nugent will become twins, but that might be a desirable thing,” Bonnie Lawrence, a Nugent student, wrote to Dean of Students Fred Turner in 1954. “Never in my life have I known a man like him. I feel that a long list of complimentary adjectives concerning him is unnecessary. It is sufficient to say that Tim Nugent has been a superior teacher, counselor, therapist, guide, and friend.”[22]

References

[1] Deirdre Lynn Cobb, “Race and Higher Education at the University of Illinois, 1945 to 1955” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Illinois, 1998), 28.

[2] Carol Huang, “The Soft Power of U. S. Education and the Formation of a Chinese American Intellectual Community in Urbana-Champaign, 1905-1954” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Illinois, 2001), 140

[3] Daily Illini, 19 May 1954.

[4] Huang, 227-28.

[5] Daily Illini, 13 December 1935.

[6] Fred Turner to Arthur Willard, 13 December 1935, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 63, F: Willard, University of Illinois Archives.

[7] Ibid., 19 October 1937, ibid., B: 67, F: Willard.

[8] Daily Illini, 11 September 1946; Cobb, 66-68.

[9] Albert Lee, “The University of Illinois Negro Students,” Arthur Willard Papers (2/9/1), B: 33, F: Colored Students, University of Illinois, University of Illinois Archives.

[10] Charles R. Frederick to Fred Turner, 15 August 1938, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 68, F: Frederick.

[11] Charles Havens to E. E. Barrett and O. M. Karraker, 27 August 1936, ibid., B: 62, F: Havens.

[12] Board of Trustees Minutes, 30 September 1936, 25,

[13] Albert Lee, “The University of Illinois Negro Students,” June 25, 1940, University of Illinois Archives Reference File.

[14] Daily Illini, 8 September 1945.

[15] Cobb, 45-50.

[16] Board of Trustees Minutes, 24 September 1946, 54; Champaign-Urbana News-Gazette, 25 September 1946.

[17] Daily Illini, 11 January 1934.

[18] Charles Havens to Arthur Willard, 17 October 1936, Physical Plant Director’s Office Subject File (37/1/1), B: 21, F: A. C. Willard, Oct.-Dec. 1936, University of Illinois Archives.

[19] Timothy Nugent to Max Durfee, 2 March 1954, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 18, F: Paraplegics.

[20] Daily Illini, 20 September 1949.

[21] Ibid., 18 April 1963.

[22] Bonnie Lawrence to Fred Turner, 18 January 1954, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 18, F: Paraplegics.

African American Student Housing at the University of Illinois: 1930 – 1950

Further Resources

Student Activities

The 1920s “country club” atmosphere on campus quickly disappeared during the Great Depression as money became scarce. By 1934, 26 fraternities either disbanded or merged. Independent students now increased their roles in athletics, publications, student government, and politics. Fun involved dating, dancing, and five-cent Cokes—in other words, whatever was cheap. Local vice, however, remained a problem, particularly from brothels on Walnut Street.

The influx in the late 1940s of GI Bill students, many with families, reinforced the serious atmosphere, though some rules were relaxed for them. By the early 1950s, the Greek system began to flourish again, and “rowdyism” returned with a vengeance, with panty raids and destructive snowball fights becoming common.

The Depression dramatically transformed the campus climate. According to a graduate of the class of 1934, when his peers had arrived on campus four years earlier, they had found “a country club atmosphere” populated by “sleek and well-dressed” Greeks. But things had changed by his senior year. “People are more serious now,” the 1934 graduate asserted. “They study. Some of them even think. The ‘hey-hey’ attitude is disdiappearing. The Greek mansions look almost as worried as do their inhabitants.”[1]

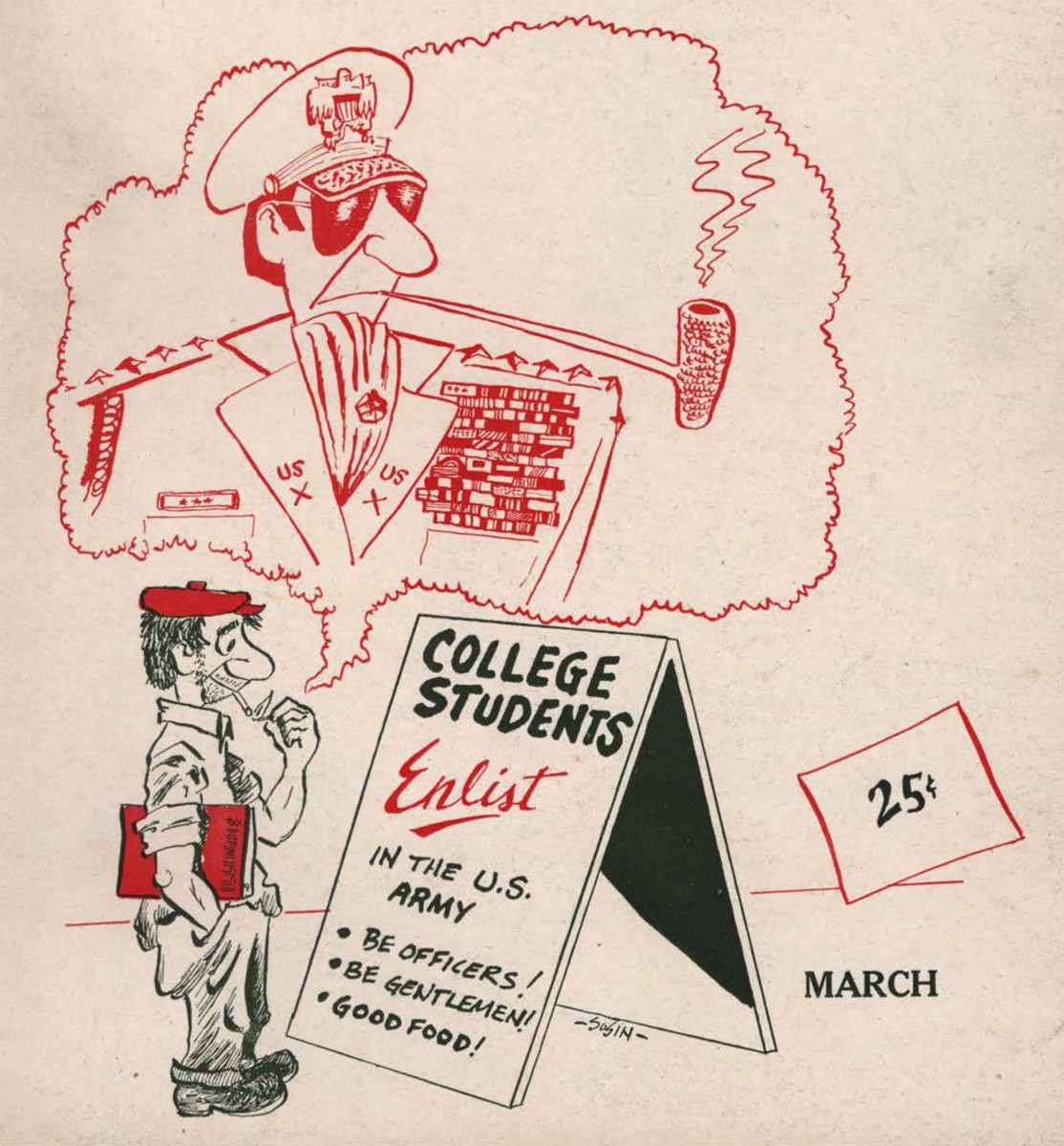

The influence of the Greeks waned during the Depression. Between 1930 and 1934, 26 campus fraternities were forced to disband or merge for financial reasons, leaving behind debts in excess of $50,000.[2] The independent students filled the resulting vacuum, taking an increasing part in athletics, dramatics, student publications, and student government.[3] A small fraction of the independents also brought political protest to the campus. Organized into such leftist groups as the Campus Forum, the National Student League, and the American Student Union, these maverick undergraduates challenged compulsory R.O.T.C., staged anti-war strikes, and participated in a campaign against campus-area restaurants that refused to serve African Americans.[4]

Many students had little time for extracurricular activities; they were too busy struggling to make ends meet. The cost of living had fallen appreciably during the Depression—in 1934 rooms cost between $8 to $12 per month compared with $12 to $20 in 1929—but money was much harder to get.[5] Some students, like the future New York Times columnist James Reston, applied to the University for loans, and even more went to work.[6] In the autumn of 1932, when the dean of men’s office took over the YMCA’s employment service, statistics showed that 989 students had obtained 4,363 jobs.[7] Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal helped students as well. First, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and then the National Youth Administration (NYA) employed an average of 1,200 students at rates of up to $20 per month. As a bonus, many of the FERA and NYA jobs were interesting; students bound books and compiled bibliographies in the Library, preserved old collections of artifacts at the Natural History Survey, and even conducted scientific research.[8] One undergraduate considered his work on an NYA project “the most valuable experience in my whole University career.” Another NYA worker, a window washer, reported seeing “many things in the various buildings that I might not have seen if I had not been working.” “I have learned something of human nature,” he declared.[9]

Students still managed to have fun during the Depression. Dating, dancing and drinking remained popular activities. Portia Allyn Smith, who attended the U of I from 1934 to 1937, recalled what dates were like in the 1930s. “Dates weren’t much, you’d have a Coca-Cola, a five-cent Coca-Cola,” Smith said. “That was about the extent of your entertainment with no money and very little time.”[10] Coca-Cola was indeed a favorite campus drink: on an average day in 1938, U of I students drank some 5,000 Cokes—235 gallons worth. Only one beer was sold on campus for every 60 Cokes.[11]

Following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, campus confectioneries began to sell beer. During the decade of the 1920s, drinking had become socially acceptable—“the badge of a free soul,” as a University committee put it—and U of I officials feared an epidemic of drinking following Prohibition’s repeal.[12] But the epidemic never materialized. Writing to President Willard in 1936, Dean of Men Fred Turner said that, while he usually saw students drinking on weekends, it was “comparatively temperate and never boisterous.” Turner continued: “Probably the worst place we have at the present time in this regard is the so-called Kamerer’s Annex, only a half block west of the campus, where more beer is consumed than at any other place near the campus.”

Bidwell’s Confectionery on Wright Street was another problem spot. An irate alumnus described the back room of Bidwell’s as “a small very dimly lighted place, badly crowded with both male and female customers . . . and empty beer bottles.” In this room, according to the alumnus, a “number of

customers were upright in the few feet in the middle of the floor, supposedly dancing, but their feet hardly moving. In the booths a number of cases of ardent love making.”[13] A few years later, Dean of Men Turner went so far as to call for the closure of Bidwell’s. “The operators of the establishment are without conscience as to what goes on there as long as they are not hurt financially, and skate along the narrow edge of ‘within the law’ and ‘it is all right if you can get away with it,’” Turner wrote to President Willard in May 1942. “We have had numerous disgraceful affairs come from there and I fear that it is inevitable that a real tragedy or major scandal will arise from the place.”[14] Bidwell’s survived until the late 1960s. By that time, Don Ruhter, the Daily Illini’s “Campus Scout,” estimated that the bar was “probably netting more from coffee sales than beer sales.”[15]

The general question of local vice became a major issue in 1937 when the Daily Illini launched a crusade against gambling and prostitution. “A couple of ambitious madames on Walnut Street run free taxi service to and from fraternities on campus,” DI editor Jack Mabley, a future Chicago Tribune columnist, reported. “It is said that more than 70 per cent of the patrons of the Walnut Street houses are students.”[16] The situation had not changed much since 1930 when Dean of Men Thomas Arkle Clark, in a letter to the Champaign mayor, identified several houses of prostitution in the city, including five on Walnut Street. (According to Clark, the Grand Hotel on North Neil Street was “the standard place for sexual irregularities.”)[17] The brothels continued to function despite the Daily Illini’s crusade, and a real vice crackdown only occurred in 1939 after a student was shot to death in the red-light district. Eleven city and county officials were ultimately indicted, and Champaign’s “great red way” went out of business, at least temporarily.[18]

After World War II, the GI Bill brought thousands of veterans to campus. Besides swelling the enrollment totals and restoring the pre-war male to female ratio, the large numbers of veterans markedly changed the tone of the campus. The veterans were serious and in a hurry to graduate and begin a career. Many of them had families to provide for and did not have the time–or the inclination–to join campus groups like fraternities. Daily Illini editor Jean Hurt wrote that many veterans “aren’t impressed by the prestige of a Greek letter name after they have been a member of a much larger fraternity–Uncle Sam’s armed forces.”[19] Perhaps not surprisingly, a certain amount of tension developed between the fresh-faced 17- and 18-year-old freshmen and the world-wise veterans. “Many veterans are registered in freshman courses,” Provost Coleman Griffith reported to President Willard. “They are more mature and often more aggressive and outspoken than the ordinary freshman who is somewhat embarrassed by them.”[20] The veterans began to disappear from campus in the late 1940s. A writer to the Daily Illini mourned the passing of this “golden era,” when school rules had been relaxed out of “a sense of unfairness in applying certain regulations to older, more worldly college students.” “Yes, the war is over,” this correspondent lamented, “and we are gradually reverting to prewar standards. Certain infractions, formerly overlooked, are no longer taken in so light a vein.”[21]

The campus returned to familiar patterns in the 1950s. The fraternity men and sorority women again came to dominate undergraduate affairs, the Greek system revived, and most students displayed an indifference to political matters. “Rowdyism” also returned with a vengeance. In November 1950, three “vicious and destructive” snowball fights pitted large fraternity groups against each other. “In one of the incidents of November 28,” Security Officer Joe Ewers reported, “it was found that Coca-Cola bottles, large cinders, lumps of coal, clubs, fire crackers, and other objects in no way related to snow balls were used.”[22] In 1952 and 1953, “panty-raid fever” swept the University; in one raid, reportedly 1,000 men targeted four sorority houses in search of “battle trophies.”[23] Like the roller-skating craze of the 1920s and the “streaking” wave of 1974, the early 1950’s “panty raids” were local versions of a national phenomenon.

References

[1] Daily Illini, 11 June 1934.

[2] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 14, 7-8, University of Illinois Archives.

[3] Ibid., 11.

[4] Roger Ebert, An Illini Century: One Hundred Years of Campus Life (Urbana; University of Illinois Press, 1967), 141-44.

[5] Illinois Alumni News, November 1934.

[6] James Reston to Thomas Arkle Clark, 25 April 1930, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 50, F: Que-Sax, University of Illinois Archives.

[7] Stephens, Chapter 14, 5-7.

[8]Daily Illini, 22 March 1936.

[9] Fred Turner, “N.Y.A . at the University of Illinois,” undated, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 62, F: National Youth Administration.

[10]Portia Allyn Smith Reminiscence, Oral History Interview, 18 April 2001, University of Illinois Student Life, 1928-38: Oral History Project, University of Illinois Archives. Transcript

[11] Illinois Alumni News, 1 May 1938.

[12] Committee on Liquor Control to Arthur Daniels, 2 December 1933, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 58, F: Repeal of 18th Amendment.

[13] Dwight L. Smith to Arthur Willard, 4 January 1938, ibid., B: 67, F: Willard

[14] Fred Turner to Willard, 18 May 1942, ibid., B: 76, F: Willard.

[15] Daily Illini, 21 November 1969.

[16] Ibid., 13 October 1937.

[17] Thomas Arkle Clark to George Franks, 8 October 1930, Harry Chase General Correspondence (2/7/1), B: 8, F: Franks, University of Illinois Archives.

[18]Ebert, 151-52.

[19] Ibid., 167, 170.

[20] Coleman Griffith to Arthur Willard, 16 October 1945, Provost Subject File (5/1/1), B: 10, F: War Veterans, Division of, University of Illinois Archives.

[21] Ebert, 170.

[22] Joseph Ewers to George Bargh, 29 November 1950, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 13, F: Ewers, University of Illinois Archives.

Dean of Men Thomas Arkle Clark puritanical reign ended with the arrival of President Chase. Chase shrank the number of student rules from 138 to 39, strengthened faculty independence in regulating their own colleges, and most importantly, gave faculty control over educational policy and student discipline.

After Chase left in 1933, Dean of Men Fred Turner lobbied new President Willard to create a more paternalistic office to regulate student affairs. This he achieved in 1943 and was named Dean of Students. In 1947, he created a Security Office. Staffed by a former Army intelligence officer, it was intended to police unauthorized drinking, etc., but in the 1950s it started surveilling alleged “subversives.” This became a big issue in the 1960s.

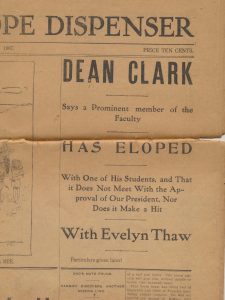

The retirement of President David Kinley in 1930 and the appointment of Harry Woodburn Chase as his successor marked the end of the lengthy reign of Dean of Men Thomas Arkle Clark. Unlike Clark and Kinley, the liberal-minded Chase believed that students should be treated as grown-ups. “I am in favor of encouraging students to assume responsibility,” Chase once said. “We ought not to multiply rules to the point where the individual is robbed of that initiative and responsibility of which I have spoken.”[1] Clark lived long enough to see much of his life’s work undone. Retiring in 1931, he died the following year of an intestinal tumor.[2] It truly was the end of an era.President Chase launched a series of reforms that gained for him almost “the stature of a liberator” among the students, according to historian Carl Stephens.[3] Under Chase’s prodding, the student handbook shrank from 80 pages to sixteen and the number of rules contained therein dropped from 138 to 39. “The only document I know comparable to our regulations for the conduct of undergraduate students is the Book of Leviticus,” Chase quipped.[4] The new president called for the loosening of rules regulating class attendance, probation, and fraternity pledging and in general encouraged student initiative.[5] The impact on students was profound. “Rules and regulations have been relaxed in every direction, and, in the case of men students, almost abolished altogether,” a 1934 report maintained.[6]

The faculty also benefited from Chase’s “New Deal.” Under Chase, the various University colleges and departments enjoyed more authority and independence. The departments were allowed to organize under either heads or chairs.[7] Chase even permitted the faculty to smoke in their offices. Gone were the days when janitors acted as spies for the administration, reporting faculty infractions of the no-smoking rule to Thomas Arkle Clark.[8] In 1941 the American Association of University Professors ranked colleges and universities according to the amount of their faculty self-governance. The U of I came in second among 228 institutions surveyed.[9]

Perhaps most importantly, Chase scrapped the Council of Administration–the powerful body that had long supervised University affairs. “It (the Council) has become what I judge to be the most autocratic body in higher education on the American continent,” Chase told Kendric Babcock, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “The greater part of what it now does should be done by Senate committees set up by and responsible to the Senate.”[10]

Acting in accord with Chase’s ideas, a faculty Committee of Nine completely revamped the Council of Administration, turning it into a purely advisory body and re-naming it the University Council. The Faculty Senate assumed most of the Council’s old powers; besides having control of educational policy, the Senate also took charge of student discipline, long the province of the deans of men and women.[11] The latter two figures no longer had “general oversight of undergraduates’ conduct,” their role being reduced to one that was merely “advisory and not regulatory.”[12] As the Illinois Alumni News put it, the deans of men and women were now “friendly advisers” instead of “campus policemen.”[13] In addition, the Senate Committee on Student Affairs was created to supervise student organizations.

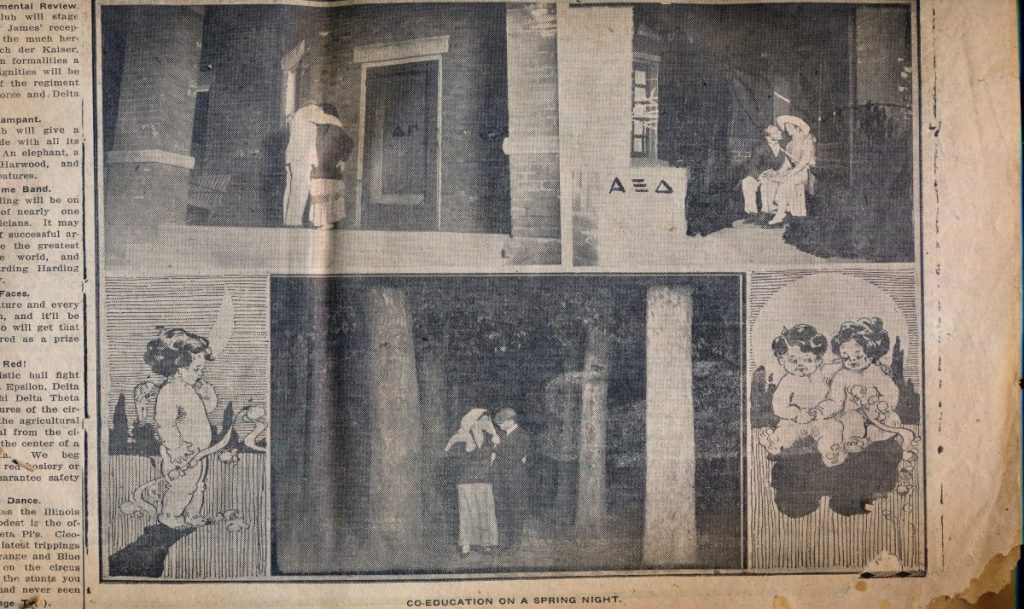

Chase left the University after only three years, but the reforms he promoted had an enduring effect on the school, whether for good or ill. Dean of Women Maria Leonard, for one, did not believe that all of this change was for the better. In a 1937 letter to President Arthur Willard, Leonard wrote of a breaking down of discipline on campus. The amorousness of college students, for example, was growing worse, she claimed. “As I told you this ‘petting problem’ with youth has increased by leaps and bounds the last three or four years, sweeping the entire country,” Leonard asserted. “All workers with youth, who are building for character, baffled parents and educators are acknowledging this.” As an aid in combatting such problems, Leonard suggested, among other things, that the old regulatory powers of the deans of men and women be restored.[14]

Dean of Men Fred Turner, a protege of Thomas Arkle Clark, also wanted more regulatory power. Surveying the field in the late 1930s, Turner believed that the pendulum on student affairs was swinging toward a “middle ground, away from the extreme liberalism of the last few years, possibly toward a more paternalistic attitude.” In keeping with this new paternalism, he called for the formation of a Division of Student Welfare with a “strong centralized administration.”[15] Lobbying President Willard for years on this matter, Turner finally got his wish in 1943 when the Office of the Dean of Students was organized. As Dean of Students, Turner had control over “the administration of student affairs” and directly reported to the president.”[16]

Dean of Students Turner had a seat on the Senate Committee on Discipline but no vote. However, in 1947, he obtained an important role in discipline through the creation of the Security Office. Though ostensibly an investigator for the Senate Committee on Discipline, Joe Ewers, Turner’s hand-picked Security Officer, was paid out of the Dean of Students budget.[17] The Committee gave Ewers, an Army Intelligence veteran, a great deal of power, allowing him to “dispose” of cases on his own initiative.[18] Ewers initially occupied his time dealing with “trivial issues” such as sunbathing on campus, “necking,” drinking, and parking violations.[19]

As the anti-Communist paranoia of the early Cold War ramped up, the mandate of the Security Office expanded to include surveillance of alleged “subversives.” In the fall of 1950, Ewers told the Board of Trustees that “10 or 15 persons with ‘will-o-the-wisp’ subversive ideas” were then under surveillance.[20] During the 1930s, Fred Turner had kept a close eye on the activities of the leftist American Student Union, and Ewers followed his boss’s lead in the 1940s and 1950s with his investigation of the Young Progressives of America (Y. P. A.).[21] In October 1950, Ewers declared in a confidential report that “the local chapter of the Y. P. A. has continued to follow the dictated policies of Communist Russia” and was therefore in violation of the Clabaugh Act—a 1947 act of the Illinois General Assembly forbidding the use of U of I facilities by “any subversive, seditious, and un-American organization.”[22] In the 1960s, the Security Office and its methods would become a big issue for student protesters.

References

[1] Daily Illini, 12 March 1936.

[2] Ibid., 19 July 1932.

[3] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 14, 35, University of Illinois Archives.

[4] Louis Wilson, Harry Woodburn Chase (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1960), 24.

[5] Ibid., 22-37.

[6] Committee on the Rooming House Problem to Arthur Willard, 15 August 1934, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 63, F: Willard, University of Illinois Archives.

[7] Stephens, Chapter 11, 9.

[8] Karl Max Grisso, “David Kinley, 1861-1944: The Career of the Fifth President of the University of Illinois” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Illinois, 1980), 570-71.

[9] Stephens, Chapter 13, 34.

[10] Ibid., Chapter 11, 3.

[11] Ibid., 8-9.

[12] Wilson, 22-37.

[13] Illinois Alumni News, February 1933, 148,

[14] Maria Leonard to Arthur Willard, 28 June 1937, Arthur Willard General Correspondence (2/9/1), B: 20, F: Leonard, University of Illinois Archives.

[15] Fred Turner to Arthur Willard, 16 January 1939, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 70, F: Willard.

[16] Board of Trustees Minutes, 31 August 1943, 494-95.

[17] Fred Turner to Charles Havens, 7 November 1946, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 6, F: Havens, University of Illinois Archives.

[18] Sub-Committee on Student Discipline, “Ten Points of Policy,” undated, ibid., B: 9, F: Ewers.

[19] Nicholas Wisseman, “Falsely Accused: Cold War Liberalism Reassessed,” The Historian 66 (June 2004), 325.

[20] Ibid., 327.

[21] Fred Turner to Arthur Willard, 15 December 1939, Willard General Correspondence (2/9/1), B: 41, F: American Student Union.

[22] Joseph Ewers to Fred Turner, 6 October 1950, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 13, F: Ewers.

![]()

Traditions & Sports

This era saw several old traditions die. Freshman cap-burning was abolished in 1931 after students—some naked—vandalized local properties. The bawdy, costumed Axe-Grinder’s Ball ended in 1935, and in 1940, the long-running Interscholastic Circus, which used to draw a thousand performers, finally petered out with only 50 participants.

Homecoming, however, crowned its first Queen in 1936; the 1951 Queen was the country’s first African American title-holder. In football, the hiring of Ray Eliot in 1941 brought the team 11 Big Ten titles and a Rose Bowl trip.

Basketball also flourished. Under coaches Douglas Mills and, later, Harry Combes, the “Whiz Kids” and their successors regularly broke records, won five Big Ten titles, and advanced to the first-ever Final Four.

Writing in 1939 at the tail end of the Depression, Tom Mayhill, a Daily Illini columnist, lamented what he saw as a decline in University traditions. “A few traditions are still lingering at the University—law seniors’ canes, no walking on the bronze tablet at Lincoln Hall, and—well, you wrack your brain for some more—that’ll convince you how scarce traditions are here,” Mayhill declared.[1] Even the “no walking on the bronze tablet at Lincoln Hall” tradition came to be disregarded. Legions of preoccupied students trudging on the Gettysburg Address tablet rendered its words “increasingly illegible,” and so, acting upon the suggestion of Lincoln historian James G. Randall, University officials placed the tablet on an adjacent wall in the mid-1950s.[2]

Mayhill’s concern was overdrawn—such University traditions as Homecoming, Dad’s Day, and Mom’s Day continued to endure—but not entirely off-base. Many traditions did die during the Depression years. The annual freshman cap-burning was abolished in 1931 after students—some naked—ran amok, smashing windows and streetlights and wrecking confectioneries. “It was a chilly night, but warm near the big fire that was in the center of a muddy field,” a participant in the final cap-burning recalled. “I don’t know how it all started. We began to throw mud at each other, then began to tear everyone’s clothes off, finally grew tired of throwing mud, and left the field to run riot through the Twin Cities.”[3]

First held in 1923, the Axe-Grinder’s Ball went the way of freshman cap-burning in 1935. A bawdy affair sponsored by Sigma Delta Chi, an honorary journalism fraternity, the ball featured student and faculty “leaders” dressed up in an assortment of outlandish costumes.[4] “It was a fun thing, and they put crazy skits on and they called people up and had you do crazy things,” Florence Hood Miner, a 1929 graduate, said of the ball. “ I can remember one time I went as a tattooed lady and I had a spangly costume and they drew pictures on my arms and my legs.”[5] And in 1940, the long-running “rowdy, noisy, colorful” Interscholastic Circus finally folded up its tent. “From a campus-wide affair with student participation and humor involving more than a thousand performers,” an observer noted, “it (the Circus) had degenerated into a colorless, disorganized affair with less than 50 participants.”[6] In addition, Homecoming lost the Hobo Parade in 1934, canceled because of a lack of interest.[7]

While one Homecoming tradition succumbed during the Depression, another was born. In 1936, Dolores Thomas Sims was crowned the first U of I Homecoming queen. Unfortunately, the Northwestern University band marred her pregame crowning ceremony, making a racket just before the “royal” introductions were to be made. The bewildered Thomas and her maids of honor soon left the field without being heard, causing at least one witness to wonder, “What happened to the Homecoming queen?”. The decade of the 1950s opened with the crowning of two noteworthy Homecoming queens. In 1950—the same year the first women cheerleaders were appointed—Mildred Fogel wore the “Miss Illinois” crown; Fogel would later be known as Barbara Bain, the Emmy-winning star of the “Mission Impossible” TV series. The following year, students chose Clarice Davis, an African American, as “Miss Illinois” in “the biggest vote for Homecoming queen in the history of the University.” According to the Chicago Defender, Davis was the first African American to hold a Homecoming queen title at a major American university.[8]

During the 1930s, Illinois athletics suffered through a “football depression”.[9] From 1930 to 1941, Robert Zuppke’s teams won only 32 percent of their games; in contrast, between 1913 and 1929, his teams had triumphed 70 percent of the time.[10] In the 1930s, The U of I band and the Block I student cheering section (begun in 1922 and first admitting women in 1934) were the real stars of the football show. One rare bright note in a dark decade came on November 4, 1939, when the Illini toppled a mighty Tom Harmon-led Michigan team, stunning the football world.[11] Confronted by a growing chorus of fans calling for his retirement, Zuppke resigned in November 1941 after 29 years at the helm of the Illini.[12] Ray Eliot, Zuppke’s successor, put together a championship team in 1946. Featuring three players from Zuppke’s 1941 squad, the 1946 eleven secured a Big Ten title with a 6-1 record and went on to upset UCLA by a score of 45-14 in the Rose Bowl.[13] In 1952, Eliot’s Illini returned to the Rose Bowl, defeating Stanford 40-7.

References

[1] Daily Illini, 28 September 1939.

[2] George Stoddard to J. G. Randall, 17 September 1951, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 15, F: Stoddard, University of Illinois Archives.

[3] Daily Illini, 11 June 1934.

[4] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 14, 15, University of Illinois Archives.

[5] Florence Hood Miner Reminiscence, Oral History Interview, 6 November 2000, University of Illinois Student Life, 1928-38: Oral History Project, University of Illinois Archives. Transcript available online.

[6] C. O. Jackson, “Where, Oh Where Are the College Circuses of Yesteryear,” The Fraternity Month, 7 (May 1940), 34.

[7] Daily Illini, 13 October 1934.

[8] John Franch, “Illinois Homecoming: A Century of Spirit,” Illinois Alumni 23 (Fall 2010), 26-28.

[9] Maynard Brichford, Bob Zuppke: The Life and Football Legacy of the Illinois Coach (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2008), 20.

[10] Ibid., 184.

[11] Ibid., 149.

[12] Ibid., 158-60.

[13] Ibid., 165-66.

[14] Daily Illini, 12 December 1943.

[15] “Harry Combes,” Wikipedia, online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Combes

[16] “Dwight Eddleman,” Wikipedia, online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwight_Eddleman

[17] “Johnny Kerr,” Wikipedia, online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnny_Kerr

![]()

World War II

The U of I became a women’s world of enrolled students during World War II as men went off to war. Women controlled the newspaper, yearbook, and many campus organizations. Men, however, flooded the campus when the University provided specialized training for the Army and Navy. Between 1942 and 1945, over 100,000 soldiers and sailors attended programs in Navy signals, diesel engine repair, medical and dental training, even cooking.

Secret work also took place among faculty. Nineteen physicists participated in the Manhattan Project. Professors created new types of synthetic rubber, an anti-malarial drug, water purity kits, and more. Unbeknownst to students, there was also a top-secret munitions lab on campus.

During World War II, the U of I campus became “a woman’s world,” in the words of the Illinois Alumni News.[1] Seemingly overnight, the ratio of civilian men to women on campus went from 3-1 to 1-4.[2] As the men went off to war, women filled the slots vacated by them, taking charge of campus organizations such as the Illio, Daily Illini, Theater Guild, and the Illini Union Board. Sororities flourished during the wartime years, enjoying record numbers of rushees, while the membership-starved fraternities languished.[3] A few women even enrolled in the College of Engineering—a traditional bastion of maleness; the education of many of these engineering students was financed by the Pratt-Whitney aircraft corporation.[4] Women also supported the war effort, enrolling in first aid and nursing classes, promoting a blood bank, and wrapping bandages in Red Cross work rooms. And Idelle Stith, an accomplished dancer, assumed the role of Chief Illiniwek in the fall of 1943.[5]

In 1943, for the first time in history, Illini women began to receive military training. Wearing a simple uniform consisting of a brown shirt, blouse, and tie, members of the Women’s Auxiliary Training Corps (WATC) drilled without weapons and received instruction in such subjects as military customs and courtesy, sanitation and first aid, and map reading. The University’s WATC program disbanded after a year or so because of a lack of interest.[6]

The men-women ratio, however, was not as lopsided as the enrollment figures suggested. There were in fact on campus large numbers of men not accounted for in the statistics tallying civilians—the thousands of Army and Navy men receiving specialized training at the University. The first members of the armed services to arrive at the University were trainees in a Navy signal school. On March 24, 1942, the Navy had given definite word of its intention of establishing such a school on campus, and University officials scrambled to meet the May 1st deadline. Dropping all of its other ongoing construction work, the University’s Physical Plant Department—under the able leadership of Charles S. Havens—launched a massive remodeling program, converting the old Men’s Gymnasium (now Kenney Gym) and the Gymnasium Annex into housing facilities and the Illini Union Ballroom into a mess hall. Masts were erected on Illinois Field to give the Navy trainees realistic instruction in the various methods of signaling between ships. Thanks to the employees in the Physical Plant Department, who in some cases worked three shifts to expedite the job, the Signal School opened on May 1st as scheduled, receiving a class of 200 trainees. The school had a capacity of 800 to 1,000 men and the training lasted for 16 weeks.[7]

In the late summer of 1942, the Navy opened schools for diesel engine operators and for diesel engine officers. The operators were housed in the Men’s Residence Hall while the officers were given rooms in the Busey and Evans residence halls. The instruction in the operation and maintenance of diesel engines took place in the cavernous West Hall of Memorial Stadium, which had been converted into workshops, laboratories, and classrooms. Also, a school for Navy cooks and bakers was conducted at the University from November 1942 to June 1943.[8]

In the summer of 1943, the Navy brought to campus its V-12 program that trained men to be medical, dental, and engineering officers. Though under Navy discipline, the V-12 trainees were instructed by members of the University faculty. They were housed and fed at Busey, Evans, and Illini Halls. In the end, some 13,000 Navy personnel would be taught on campus in these various schools and programs during the course of the conflict.[9]

The Army too had a strong presence on campus during the war years. Unveiled late in 1942, the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) was organized to provide soldier-students with instruction in engineering, psychology, foreign languages, medicine, dentistry, or veterinary science. At the program’s peak more than 100,000 ASTP men were studying at nearly 200 colleges.[10] The University of Illinois offered instruction for over 14,000 ASTPers from July 1943 until March 1946. Late in 1943, there were as many as 3,383 ASTP trainees on campus at the same time, living in 45 of the University’s 52 fraternity houses. In the spring of 1944, the federal government sharply curtailed ASTP as increasing numbers of soldiers were needed for the ongoing Italian campaign and for the planned invasion of France.

Like their Navy V-12 counterparts, the uniformed ASTP trainees were taught by largely civilian instructors. The ASTP men had a formidable course load during their twelve-week-long terms. They attended school 34 hours a week and their study was supervised between classes and from 8:30 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. each weekday night. “The only time they have for their own pursuits is from the minute they finish the evening meal until night study begins,” the Illinois Alumni News note.[11]

The masses of soldiers and sailors dramatically transformed the look and feel of the University. According to one witness, the large numbers of men in uniform made the campus seem like “some sort of combination military-naval reservation.” To another observer, the rows of marching Navy bluejackets gave the Quad the appearance of the “Brooklyn Navy Yard.” A so-called section marcher shepherded the ASTP men to class. When the ASTPers reached the doors of the classroom building, the section marcher bellowed “AT EASE.” Once inside the classroom, the Army trainees remained standing until the section marcher roared “TAKE SEATS.”[12]

On Victory in Europe Day–May 8, 1945–more than 3,000 students gathered in front of the Auditorium for a brief service. President Willard set the tone for the assembly, telling the crowd that “we have not met here today to celebrate our great victory in Europe, but rather to rededicate ourselves to the winning of the final victory over Japan.” That long-awaited outcome finally arrived on August 15th and the University celebrated with a two-day holiday. When news of the war’s end was leaked the previous day, the campus went wild. “Crowds which began dashing back and forth on Green and Wright streets shortly after six gathered into an ecstatic mob who marched and sang and shrieked their happiness above the violent discord of many car horns,” a witness reported.[13]

In the months and years following the war, the full extent of University involvement in wartime research was revealed. Nineteen University physicists had taken part in the Manhattan Project that produced the world’s first nuclear bomb. Physics Professor F. Wheeler Loomis had been an associate director of the Cambridge, Massachusetts laboratory that had developed radar. Chemistry Professor Roger Adams had served on the National Defense Research Committee.