For the University of Illinois, the 1920s was a decade of physical growth—rising enrollment and rising buildings—and academic stagnation. New York architect Charles Platt gave Illinois a signature Georgian Revival architectural style and a campus plan for the ages. Illinois football reached new heights as Harold “Red” Grange galloped into history. And the students let loose, dating, dancing, and drinking to an unprecedented extent. The hazy outlines of the modern public university—the “Big U” of the 1960s and beyond–could be glimpsed on the distant horizon.

Further Resources

![]()

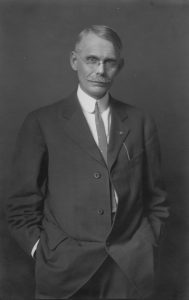

Administration

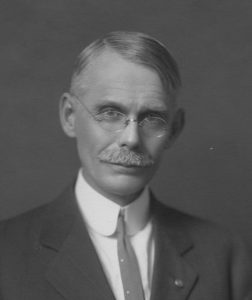

The “Roaring Twenties” posed a particular problem for campus administration as old social norms went out the window. Dean of Men Thomas Arkle Clark disapproved of jazz, new dance styles, drink, and student “love-making” (“Intimate physical contact is not necessary to enjoyment between the sexes,” he wrote).

Using an army of informants, he tried unsuccessfully to crack down on drinking and speak-easies (even Eliot Ness once came in 1927 to enforce Prohibition). He also managed to get a campus-wide ban on automobiles, claiming they promoted drinking and “social immorality.” No wonder the campus was considered the most puritanical in the country.

“Intimate physical contact is not necessary to enjoyment between the sexes.”

Dean of Men Thomas Arkle Clark

Growing Enrollment

During the 1920s, college became “the thing to do” for more and more young adults, with the number of those attending college in the United States doubling in the decade. The University of Illinois received more than its fair share of these new, now predominantly urban, students. In 1920 the per-semester tuition was raised from $15 to $20, but the students still came.[1] The following year, the University had over 10,000 students for the first time–the third largest enrollment in the country, behind only California and Columbia.[2] Legislators began expressing concern over the U of I’s size, and there was talk of limiting admissions and even of “breaking up” the University.[3]

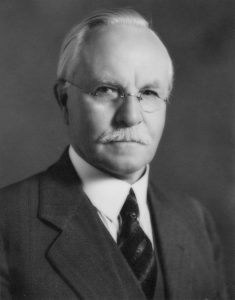

President David Kinley, on the other hand, believed that the U of I needed to become even bigger in order to accommodate the increased enrollments. In 1919 the 58-year-old Kinley took over the reins from the ailing President James. (Kinley would be the acting president until 1920.) Kinley, a Yale-trained economist, was a natural for the role, having loyally and competently served the University for over 25 years, including as the dean of the Graduate School and as James’ sometime “hatchet man.”[4] Cold, humorless, and brusque, Kinley, however, inspired admiration rather than real affection. “Another man from the East and I think they had better kept him there,” the legendary naturalist Steven Forbes, then the UI College of Science dean, supposedly said of Kinley shortly after they first met in 1893.[5] Not helping matters, the U of I president also possessed a volcanic temper he had trouble controlling. According to Charles Hottes, a Botany professor, Kinley once became so angry during a meeting with a student that he began kicking a wastebasket around his office.[6]

Kinley may not have won a popularity contest, but he was a hard worker who got things done. He had a strong interest in the physical plant of the University and in campus planning. Launching an ambitious ten-year plan, Kinley sought vastly larger appropriations from the Legislature to meet the needs of the growing University. Materially aided by business groups and alumni, the U of I’s legislative campaigns achieved incredible results: The biennial appropriations averaged $10.5 million during the decade, almost double the largest amount received during the James administration in a single biennium.[7] A large fraction of this money was spent on buildings: over a dozen structures were constructed during this decade, most on the south campus. The south campus buildings were designed by New York architect Charles Platt in the University’s new signature Georgian Revival style and were sited according to the dictates of Platt’s landmark 1922 Campus Plan.[8]

The Daily Illini later lauded Kinley for solving what it termed was “the chief problem” of his administration—“the erection of a physical plant that would provide adequately for the 10,000 sons and daughters of Illinois who sought education here.”[9] With this mission accomplished, the 68-year-old Kinley retired in the summer of 1930 after thirty-seven years of service to the University.[10] He had gotten out in the nick of time—just before the campus felt the full effects of the Depression.

References

[1] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 9, 23, University of Illinois Archives.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 7.

[4] Karl Max Grisso, “David Kinley, 1861-1944: The Career of the Fifth President of the University of Illinois” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Illinois, 1980), 613-14.

[5] Charles Hottes Reminiscence, Oral History Interview, 14 January 1964, Charles F. Hottes Papers (15/4/21), B: 2, Reel 2, University of Illinois Archives.

[6] Ibid., November 1963.

[7] Stephens, Chapter 9, 10-11.

[8] Ibid., 13-15.

[9] Daily Illini, 24 April 1930.

[10] Ibid., 2 June 1929.

![]()

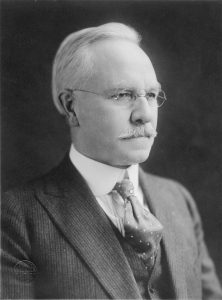

Academics

After the huge influx of big-name professors and campus expansion under President James, the priorities of new president David Kinley did not sit well with many on campus. Although an economics professor since 1893 and a dean, faculty considered him abrasive, autocratic, and more concerned with public relations than academic freedom.

The result was few new departments or course offerings, more graduate students as instructors, and an exodus of distinguished faculty. Even reading assignments came under President Kinley’s scrutiny when professors tried to assign questionable books such as James Joyce’s Ulysses. He retired in 1930, after 10 years at the helm.

Many faculty members believed that, in the David Kinley administration, academics took a back seat to “architecture, construction, and landscape gardening.”[1] They could point to what were, for them, evidences of academic decline from the halcyon James years: a curriculum that remained essentially stagnant, with few new departments being launched and few new courses being introduced; an increase in class sizes; a growing reliance on graduate students as instructors; faculty salaries that failed to keep up with the pace of inflation; and an exodus of distinguished faculty members, including History’s Clarence Alvord and Evarts B. Greene, Engineering’s Charles Richards, and English’s Stuart Sherman.[2]

Kinley’s abrasive personality, autocratic nature and conservative outlook did not endear him to most members of the faculty. Early in his tenure, he bitterly opposed a faculty union attempting to improve the status of its overworked and underpaid members.[3] Kinley insisted that faculty members hold “conventional social, political, and religious viewpoints,” in the words of his biographer.[4] He carefully vetted the resumes of faculty candidates, making sure that no socialists or pacifists joined the instructional staff.[5]

Valuing public relations over academic freedom, Kinley urged historian Arthur Cole, an avowed socialist and the organizer of the faculty union, to moderate his political positions. (Having exhibited a “lukewarm attitude” toward the World War I effort, Cole had incurred the enmity of Trustee Mary Busey whose son had died in the war.) Encouraged to leave the University, Cole ultimately accepted a position at Ohio State in 1920 and would go on to have a distinguished career as an historian.[6] “Kinley did not object to Cole’s socialist ideas or to his union activities so much as to the reaction those ideas and activities might arouse outside the University if they became a matter of public controversy,” Kinley’s biographer wrote. “Therefore, Kinley’s resistance to and at times suppression of academic freedom at Illinois was not so much a matter of principle as it was a part of public relations.”[7] To be fair, the American Association of University Professors’ principles of academic freedom had only recently been promulgated.

Even reading assignments came under scrutiny in the Kinley administration. After a parent complained about one assigned book—Guy de Maupassant’s Bel Ami—Kinley ordered the English Department chairman Ernest Bernbaum to put an end to “the assigning of dirty reading.”[8] University Librarian Phineas Windsor aided Kinley in his censorship efforts, keeping a close eye on what books were being borrowed and which ones were being reserved for classes. In 1927 Windsor alerted Kinley to the fact that English Professor Jacob Zeitlin had assigned James Joyce’s Ulysses to an undergraduate working on a paper. Responding, Kinley commanded Kendric Babcock, dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, “to advise Professor Zeitlin that we cannot permit such assignments in the future.”[9]

David Kinley retired in 1930 after thirty-seven years of service to the University. Ironically, the man who, early in his career, had opposed Andrew Draper for being too autocratic ended up being eerily similar to Draper, just as guilty of “overcentralization and overregulation.”[10] Kinley’s retirement capped a decade that saw many of the University’s long-time faculty step down, including Isabel Bevier, Stephen Forbes, Ira Baker, William Noyes, and Arthur Talbot. The old-guard from the early James years and before was exiting the scene.[11] “The University is changing a good deal these days,” Dean of Men Thomas Arkle Clark reported to a friend in 1928. “All the old timers are either retired or will soon be ready for retirement, and there is a new crop coming on. They will probably do better than we have done.”[12]

Professor Joseph Tykosinki-Tykociner arrived at the University of Illinois in 1921 as an experienced electrical engineer dreaming of bringing sound to film. As the first research professor in the electrical engineering department, his invention of the “talkie” was revolutionary not only in commercial film, but also in expanding the College of Engineering and the possibilities of scientific research at the University. Unfortunately, the patents of his invention were quickly caught up in University politics and he was never able to commercialize his invention. Tykociner stayed at the University for another 25 years, pioneering research in zetetics and photolectricity. Tykociner’s Demonstration of Sound on Film Technology

Further Resources

Joseph Tykociner and the “Talking Film”

Investing in Gadgets that Improve Lives: Sound on Film

Joseph T. Tykociner Papers, 1900-69

References

[1] Frank W. Scott to Thomas Arkle Clark, 5 October 1930, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 52, F: Scott, University of Illinois Archives.

[2] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 9, 17-22, University of Illinois Archives.

[3] Karl Max Grisso, “David Kinley, 1861-1944: The Career of the Fifth President of the University of Illinois” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Illinois, 1980), 575-77.

[4] Ibid., 530.

[5] Ibid., 555.

[6] Ibid., 557-64.

[7] Ibid., 564.

[8] Ibid., 568.

[9] Ibid., 568-69.

[10] Ibid., 570.

[11] Stephens, Chapter 9, 19.

[12] Thomas Arkle Clark to Harlan Horner, 19 November 1928, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 47, F: Horner.

Further Resources

![]()

Campus Architecture & Planning

With enrollment in 1919 burgeoning and buildings bursting at the seams, then-Acting President Kinley identified the university’s chief need as being at least 14 new structures and 12 additions. The Board of Trustees therefore created a Campus Plan Commission to find a way to accommodate at least 10,000 students. Their recommendation: hire New York architect Charles Platt.

Within five years, Platt’s first building, the Agriculture Building, was dedicated. Its Georgian Revival style became the template for all campus buildings of the era (David Kinley Hall, Evans Hall, Huff Hall, McKinley Hospital, University Library, etc.). His greatest innovation—arranging buildings in masses rather than siting them haphazardly.

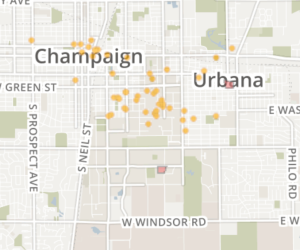

Jazz Age Building Tour: 1920 – 1930

The flood of students entering the University in the 1920s threatened to overwhelm the school’s physical plant. The old Library (Altgeld Hall) could comfortably accommodate only 265 students at a time when a thousand or so typically needed to use it. The Men’s Gymnasium (Kenney Gym) had classes going on in it until ten at night. Students were packed like sardines in the laboratories. With the growth in enrollment expected to continue into the foreseeable future, the University clearly needed additional buildings—and lots of them—to accommodate all of the new students.

Late in 1919, Acting President David Kinley conducted a survey of the University’s building requirements and discovered that at least fourteen new structures and twelve additions were urgently needed. In response, Kinley launched a bold building program to solve what the Daily Illini later described as “the chief problem” of his administration—“the erection of a physical plant that would provide adequately for the 10,000 sons and daughters of Illinois who sought education here.” [1] Development on such a scale demanded a great deal of planning, and the Board of Trustees responded by creating a Campus Plan Commission to direct this growth. Unlike its architects-only predecessor of a decade before, this plan commission contained a mixture of Trustees and academics—and not a single architect. After almost three years of service, the commission went out of business in the fall of 1922 when the trustees approved “in general” the historic campus plan of Charles Platt.

Over a year before, the trustees had appointed Charles Adams Platt to a dual role: to serve both as the architect of the new Agriculture Building (Mumford Hall) and as a consultant on the U of I campus plan. An aristocratic New Yorker, the French-speaking, croquet-playing, bewhiskered Platt had been the number-one choice of a trustee-appointed committee headed by Martin Roche, of the renowned Chicago architectural firm Holabird & Roche. “Mr. Platt is an artist, an architect, and a landscape gardener, but he is also at bottom a practical man,” Roche declared in his letter of recommendation.

Despite a bout of pneumonia that had confined him to a Chicago hospital early in 1922, Platt worked quickly on the designs for the new Agriculture Building and by April had already completed the preliminary plans. Dedicated in 1924, the new Agriculture Building would set the standard for future building design on campus. Built in a Georgian Revival style, new Agriculture was a three-story (plus attic) red-brick horizontal mass trimmed in limestone and topped by a steeply-slanted, green-slate roof and a profusion of over-sized false chimneys. Platt’s other campus buildings—David Kinley Hall (1925), Evans Hall (1925), Huff Hall (1925), McKinley Hospital (1925), the Library (1926-9), the Armory Additions (1927), Architecture (1928), the President’s House (1930), the Agricultural Bioprocesses Lab (1931), and Freer Hall (1931)–would share many of these basic features.

Having established Georgian Revival as the University’s dominant architectural style, Platt also set the course of future UI development with his epochal 1922 campus plan (revised in 1927). The architect accepted the basic outlines of previous campus plans, including the main north-south axis established in the 1906 Blackall plan and the east-west mall proposed by Holabird and Roche in 1920, though shifted somewhat north. Platt’s great innovation was his arrangement of his buildings in masses—masses connected to each other by ornamental gateways and enclosing cozy inner courtyards. Platt’s imposing structures had both public and private faces. On the side facing the broad malls, they presented a monumental front with uniform high cornice lines; the view from the courtyards, on the other hand, was much different: more human and homey, with lower cornice lines and a reduced scale of detail.

Even a student or two noticed Platt’s handiwork. Writing early in 1924, a Daily Illini editorialist praised the University’s new campus plan. “Illinois is expanding in the right way,” he or she wrote. “New buildings, instead of being strewn indiscriminately, are being built according to a well laid out campus plan. . . . Walks between classes may seem a bit long now, but it is better to sprint a bit than to have a campus spattered out and mixed with business houses and dwellings, as other institutions which have under-estimated their own growth find themselves today.” [2]

References

Information for this unit came from Lex Tate and John Franch, An Illini Place: The Campus of the University of Illinois (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, forthcoming).

[1] Daily Illini , 24 April 1930.

[2] Daily Illini , 15 February 1924.

Further Resources

![]()

Diversity

Campus demographics changed radically during the 1920s, with urban students outnumbering rural ones for the first time ever. International student numbers also decreased as some foreign countries began their own universities and others suffered financial setbacks.

African-American enrollment, however, soared to 138 by 1929. Nevertheless, discrimination permeated everything from housing, causing many to join African-American sororities and fraternities, to classes (President Kinley personally ordered one professor to end segregated classroom seating). Jewish students, too, felt discriminated against, leading to creation of the country’s first Hillel Foundation. They also had common cause with African-American students when the campus Interfraternity Council barred African-American and Jewish fraternities from membership.

During the 1920s, the student body was predominantly urban for the first time in the history of the U of I.[1] These newcomers from the cities gave the campus a different tone. The Daily Illini somewhat snobbishly described the trend as one that led away from “the hairy-chested, he-man, farmer college to a more sophisticated, more social, more ‘Eastern,’ if you will, institution.”[2] Despite the growing enrollments, the make-up of the student body became “more nearly homogenous than it had been ten years before,” historian Carl Stephens reported.[3] Proportionally fewer students came from out of state, and the number of international students declined, going from a peak of 278 in 1921 to 169 in 1928-9.[4] Beginning in 1921, out-of-state students were charged more for tuition for the first time: $37.50 per semester compared to the $25 per semester paid by in-state students.[5]

International Student Programs

The enrollment of international students at the U of I fell 69 percent between 1921 and 1925.[6] More international students were attending new universities in their home countries. Japan and the Philippines, for instance, had developed “institutions of higher education during the past few years that rival some American institutions.”[7] Beset by economic difficulties, many overseas nations also offered fewer scholarships to students planning to study abroad. Unfavorable rates of exchange helped cause the decrease in the number of European and Latin American students. “Four Chilean pesos were worth one American dollar several years ago while today 10 pesos must be given in exchange for an American dollar,” a student from Chile explained. “This deflation in South American money has caused many students to give up hopes of continuing their education in American institutions.”[8] As in the 1910s, China provided the most international students: their numbers peaked in 1921 when there were 88 Chinese students at the University.[9] According to a Chinese graduate student, the Immigration Act of 1924 (which further restricted Chinese immigration) played a role in curtailing Chinese student enrollment at the U of I.[10]

Found in RS 26/4/1

The number of African American students rose markedly in the 1920s, topping out at 138 in 1929.[11] As their predecessors, these students faced discrimination on and off campus. In 1926 President Kinley personally intervened to end a segregated seating arrangement set up by a chemistry professor and ordered Graduate School Dean Arthur Daniels to “quietly and discreetly make certain that such a thing did not occur again.”[12] According to Albert Lee, the unofficial Dean of African American students, the Women’s Residence Halls were theoretically open to African American students. But, Lee went on to explain, “there are practical difficulties that almost preclude their living there. The expense, the early deposit, and the long waiting list are factors that influence the situation.”[13] Barred from most campus-area boarding-houses, African American students had few rooming options. Many chose to live in one of the three houses owned or rented by the Kappa Alpha Psi and Alpha Phi Alpha fraternities and the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority.

As with boarding-houses, campus-area restaurants were off-limits to African American students—except for the cafeteria in the Woman’s Building, which only served lunch. Those few African Americans who dared to enter a campus restaurant were inevitably treated badly. “Even in the place where I work the boss told us that if any colored person came in to take our time about waiting on them and give them poor service because he doesn’t want to encourage their trade,” Jacob Goldstein, a Jewish student and an employee at a campus eatery, wrote in 1929. “We must serve them because that is the law. Sometimes those fellows wait fifteen or twenty minutes before they get any service and I really feel sorry for them.”[14] In 1927, Theophilus Mann, an African American law student, sued Lula Spang, the owner of a campus-area restaurant, on grounds of discrimination for refusing to serve him. An all-white jury took only a few minutes to find Spang not guilty. Spang claimed that she had offered to serve Mann and his friends in “a back room of the eating establishment,” and, for the jurors, this assertion was enough to absolve her of guilt.[15]

In the autumn of 1923 African American students at the U of I launched a publication, unique for the time, called “The College Dreamer” whose purpose was “to make the college life of their fellow students more enjoyable.” The first issue totaled sixteen pages and featured articles by Dean of Women Maria Leonard and Leah Fullenwider, an English instructor and a future Dean of Women, as well as by students, a few poems, and a sporting page “devoted to negro athletes.”[16] After the publication of three issues, the pioneering “College Dreamer” experiment apparently ended. “For a newcomer in the field of magazines, ‘The College Dreamer’ has served well to reflect the progress being made by Negro students in American universities and colleges,” the Daily Illini declared.[17] Unfortunately, no copies of “The College Dreamer” are known to exist.

Hillel Publications

Jewish students faced prejudice as well. “With all this blah blah of democratic feelings in this University etc. a Jew doesn’t have much chance nor is he loved any too much,” Jacob Goldstein, a U of I undergraduate, wrote to a friend in 1929.[18] Many Jewish students found refuge in national fraternities and sororities of their own: Zeta Beta Tau, Sigma Alpha Mu, Alpha Epsilon Pi, Tau Epsilon Phi fraternities all had chapters on the campus in the 1920s as did Alpha Epsilon Phi, Sigma Delta Tau, and Delta Phi Epsilon sororities.[19] The 1923 founding of the Hillel Foundation on campus proved to be a watershed moment for Jewish students. “Hillel Foundation at the University of Illinois was the first serious attempt in history to provide systematic religious contact for American college students of the Jewish faith,” Winton Solberg wrote. “Hillel strove to cultivate a deeper and richer life for Jewish students.”[20]

References

[1] <a Illinois Alumni News, 10 February 1930, 217-23

[2] Daily Illini, 27 May 1926.

[3] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 9, 40, University of Illinois Archives.

[4] Ibid.; Carol Huang, “The Soft Power of U. S. Education and the Formation of a Chinese American Intellectual Community in Urbana-Champaign, 1905-1954” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Illinois, 2001), 140.

[5] Stephens, Chapter 9, 23.

[6] Daily Illini, 7 March 1926.

[7] Ibid., 8 January 1925.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Huang, 126.

[10] Daily Illini, 7 March 1926.

[11] Huang, 128.

[12] Karl Max Grisso, “David Kinley, 1861-1944: The Career of the Fifth President of the University of Illinois” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Illinois, 1980), 632.

[13] Albert Lee, “The University of Illinois Negro Students,” June 25, 1940, University of Illinois Archives Reference File.

[14] Jacob Goldstein to Lena Wolkow, 28 October 1929, Jacob Goldstein Papers, B: 1, F: 28 October 1929.

[15] Daily Illini, 19 November 1927.

[16] Ibid., 7 November 1923.

[17] Ibid., 15 May 1924.

[18] Jacob Goldstein to Lena Wolkow, 1 November 1929, Jacob Goldstein Papers, B: 1, F: 1 November 1929.

[19] Winton Solberg, “The Early Years of the Jewish Presence at the University of Illinois,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, 2 (Summer 1992), 223-24

[20] Ibid., 229.

Further Resources

![]()

Student Activities

The student in the University may or may not agree with the dean’s ideas, or with the University rules. He may think that drinking and other sub-rosa activities are perfectly proper here or anywhere else. He observes the University rules almost altogether for just one reason – he has the fear of the dean in his heart. Daily Illini , May 18 1926

A leader in enrollment and in campus planning, Illinois also helped shape the nation’s view of 1920s-era college life. Two important novels by Illini authors dealt with this watershed period when sexual mores, gender roles, hair styles and dress all changed profoundly. First out of the gate was Town and Gown, co-authored by Lois Seyster Montross, a 1919 U of I graduate. Clearly based on Montross’ own experiences at the U of I, the 1923 episodic novel offered an unblinking—some said “unwholesome and indecent”–look at various students caught up in the dramatic cultural shifts of the time. According to a reviewer, Town and Gown did “for the coeducational institutions of the middle west what (F. Scott Fitzgerald’s) This Side of Paradise did a year or so ago for Princeton.”[1] Published much later, William Maxwell’s 1945 autobiographical novel The Folded Leaf provided an invaluable look backward at U of I student life in the 1920s.[2] Maxwell pulled no punches in his account, even telling of his 1928 suicide attempt.[3]

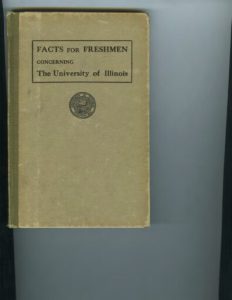

The Greeks dominated student life during the 1920s. By the end of the decade, the University could legitimately call itself the fraternity and sorority “capital of the world.” Over one-third of the student body belonged to one of the 88 fraternities and 44 sororities on campus in 1929.[4] Besides room and board, Greek organizations offered students comradeship, “dancing and dates,” and that highly prized, elusive commodity known as “prestige.” Independents did not have prestige and were looked down upon by the Greeks as “Barbs”–short for “Barbarians.”

The Greeks had distinctions among themselves. Certain Greek houses were “rated” higher than others, and individual Greek men and women were judged similarly. “A woman to rate must be fairly pretty, dance well, be able to talk glibly (not necessarily intelligently) about dancing and shows and people about the campus,” the Daily Illini explained in 1926. “. . . She must wear good clothes, and must have a snappy come back . . . for almost any line. She must be willing to listen part of the time, and must betray a certain interest in what her date wants to talk about.” For a fraternity man to rate high, he “must know reasonably well how to wear clothes, and be able to dance with some proficiency. He must have some interesting topic of conversation and be willing to listen to the woman. He must not have any noticeable idiosyncrasies and be reasonably well mannered.” Also, owning a car was a big plus.[5]

Fraternity and sorority members set the tone for student culture in the 1920s. Flappers were often sorority women, and “Joe College,” with his class cap, clay pipe, and raccoon coat, usually belonged to a fraternity. Most of the era’s “crazy cars”–wildly decorated rust-buckets–were owned by fraternity men.[6] The Greeks also did much of the dating and dancing on campus. And there was a lot of dancing going on in the 1920s. During a single May weekend in 1927 a whopping forty-six dances were held near campus.[7]

Palatial new fraternity and sorority houses served as the setting for many of these dances. Greek house building boomed during the 1920s. Between 1926 and 1928—the peak years of the boom—some 26 chapter houses were constructed at a cost of roughly $2 million dollars. These opulent residences exhibited a hodgepodge of architectural styles ranging from Tudor Revival to Georgian and Neo-classical, with even a few exotic Chateauesque, French Eclectic, Italian Renaissance, and Mission specimens thrown into the mix.[8] “With the recent progress in sorority and fraternity building, Illinois can now boast one of the most beautiful campuses in the country, as far as the chapter houses of the national organizations are concerned,” the Daily Illini puffed in 1929, near the end of the construction boom. “Few chapters of any organization have any more lavish and pretentious residences in any school than they have at Illinois.”[9]

Long on the sidelines, the Independents—mostly scattered in boardinghouses across campus–finally began to organize during the 1920s. Spearheaded by Irene Pierson, the Woman’s Group System (WGS) sought to “bring the advantages of organized life to the unorganized.” Under this scheme, Independent women were assembled into groups according to their residences, and these groups in turn formed a council of the Woman’s League, just as individual sororities make up the Pan-Hellenic Council. “Group activities were thus stimulated equally among all women,” historian Carl Stephens explained.[10] For the Independent men, a so-called “unit system” was set up to enable every man to take part “in all of the intramural activities that fraternities engaged in.” There were eighty-six separate geographical units, each of which had its own name, constitution, and set of officers.[11] The “unit system” died out after its originator was graduated, but the idea was revived several years later by W. J. “Johnny” Granata, “a politician de luxe.”[12] Granata also promoted the Independent Council, which, according to Stephens, “helped freshmen with registration, sponsored bridge, billiard, and athletic tournaments, dances and smokers.”[13]

Besides the Greek and Independent organizations, there were over one hundred student groups catering to every possible interest. For religiously-inclined students, the emergence of religious foundations on campus in the 1910s and 1920s seemed to be the answer to their prayers. In 1913 the Wesley Foundation–“the first institution of its kind”–led the way in providing religious instruction to U of I students.[14] During the 1920s, more religious foundations followed, a trend encouraged by President David Kinley, a devout Presbyterian. “There can be no complete education without religious training,” Kinley once declared.[15] By the end of Kinley’s decade-long tenure as U of I president, there were six foundations on the campus: Wesley (Methodist), Newman (Roman Catholic), Hillel (Jewish), McKinley (Presbyterian), Disciples of Christ, and Congregationalist. Besides offering religious instruction, the foundations served as social and recreational centers for students of a common faith.[16]

References

[1] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 9, 26-27, University of Illinois Archives.

[2] William Maxwell, The Folded Leaf (New York: Vintage International, 1996).

[3] Urbana Daily Courier, 27 April 1928.

[4] Robert Jacobs, “The Fraternity System at the University of Illinois,” Greek Affairs Subject File (41/2/48), B: 55, F: Jacobs, University of Illinois Archives.

[5] Daily Illini, 26 May 1926.

[6] Stephens, Chapter 9, 32-33.

[7] Thomas Arkle Clark to David Kinley, 6 May 1927, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 43, F: Kinley, University of Illinois Archives.

[8] Daily Illini, 18 March 1928.

[9] Ibid., 21 April 1929.

[10] Stephens, Chapter 9, 28-29.

[11] Ibid., 34-35.

[12] Thomas Arkle Clark to Harry Woodburn Chase, 4 May 1931, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 51, F: Chase, University of Illinois Archives.

[13] Stephens, Chapter 9, 35.

[14] Daily Illini, 17 March 1928.

[15] Ibid., 8 March 1925.

[16] Stephens, Chapter 9, 41.

The “revolution in morals and manners” of the 1920s pitted many free-spirited students against their more conservative and authoritarian elders. Dean of Men Thomas Arkle Clark was firmly on one side of the generation gap. Dismissing the 1920s as “an unconventional era,” Clark continued to exercise close supervision over the male students in the belief that they were “irresponsible, thoughtless, and without the ability to think for themselves,” in the words of the Daily Illini.[1] Walter Deuel, a 1926 U of I grad, was on the other side of the generational divide. “I’ve enjoyed guzzling drinks, and necked some too,” Deuel wrote to Clark in 1929. “But I think it’s too bad to keep on treating college men and women like a gang of irresponsible ten-year-olds.”[2]

Writing in 1927, the Daily Illini claimed that the U of I had a national reputation as “the most Puritanical seat of higher learning.”[3] Clark deserved much of the credit for this alleged reputation. “The dean is credited by the average undergraduate with divine powers—conscience, omnipotence, omnipresence,” the student newspaper reported. “He or his agents are looked for behind every tree, in every stranger, and in every booth.”[4]

With its changing moral notions, the decade of the 1920s posed a particular challenge for the conservative Dean of Men. Much to the consternation of people like Clark, many youth of the era hungrily embraced what one author memorably called the “modernity of jazz and jungle dancing, of raw styles and rouge, of novels and frankness and unashamed sex.”[5] The flapper, with her “bobbed hair, stream-line eyebrows, plastered cheeks, rouged lips, form-exposing skirt, and throaty voice,” became a symbol of the decade’s unconventionality and sexual openness.[6]

Clark had “scant sympathy” for student “love-making” and deplored the “petting” phenomenon that swept college campuses in the 1920s.[7] “Intimate physical contact is not necessary to enjoyment between the sexes,” he flatly asserted.[8] A Daily Illini editor openly wondered whether the mighty Dean of Men had “at last encountered something which defies even the unlimited powers of the University administrative authorities?”[9]

Clark’s concerns about the era’s increasing sexual freedom were shared by many others. In 1922 a wealthy Vermilion County farmer reported that he had heard “183 girls went wrong in one year” at the U of I; as a result, he told his daughters that “they could attend any school in the United States . . . except the University of Illinois.”[10] Dean of Agriculture Eugene Davenport took issue with this claim, saying that in his twenty-eight years at the University he knew of “but two or three instances where a girl in this institution went wrong.” “The people attending here are from the best families in the best communities,” Davenport wrote, “and the very best conditions are maintained which can possibly be maintained among young people.”[11]

Drinking was another favorite past-time of many students in the Prohibition era. In November 1923 a senior described the scene inside a caravan of Pullman cars journeying from Champaign to Columbus for a big football game. “Those Pullmans were certainly the wildest places I ever saw,” he wrote to his girlfriend. “A bottle in every hip pocket–girls that never did anything out of the way in their life before were dead drunk.” The entire football weekend turned out to be a “grand and glorious party,” the senior declared. “. . . I never saw so much booze in my life. Everyone was hilariously happy all the time. I cannot tell a lie. I guess I was too.”[12]

Thomas Arkle Clark took a hard line against drinking. “He is credited with dismissing men for drinking without being in the least drunk,” the Daily Illini said of Clark.[13] The Dean of Men used his wide network of informants to uncover the local sources of illegal liquor. Writing to President Kinley in 1921, Clark reported that liquor could be obtained from a porter at Kandy’s Barber Shop on Green Street and from attendants at the Orpheum Theatre. (He also told Kinley that a student secured opium and hypodermic needles at Schuler’s Ice Cream Parlors on Main Street in Champaign.)[14] He investigated the matter further the following autumn and turned up additional alcohol providers, including two Green Street billiard halls, the Eat-Mor restaurant on Wright Street, certain drug stores in Champaign and Urbana, and various local physicians. Clark believed that most of the liquor was coming via automobile from Canada through Detroit and Gary, and that the principal bootleggers were “Greasy” Gillespie and “Red” Ludwig, two veterans of the Champaign-Urbana vice scene.[15]

Illegal liquor continued to flow into the area throughout the 1920s. In the spring of 1927 none other than Eliot Ness–the future “Untouchable” and antagonist of Al Capone–made an appearance in Champaign-Urbana as a Prohibition enforcer. Wearing “the official pin of Sigma Alpha Epsilon . . . and dressed in clothes that would do credit to the most representative man on campus,” Ness looked every inch the collegian as he gathered evidence against eight “resorts” selling illegal “booze.”[16] However, the efforts of Prohibition agents like Ness barely made a dent in the local liquor trade. The following year, Thomas Arkle Clark reported that four Champaign men were operating “speak-easies” within sight of the police station, their alcohol apparently being furnished by Chicago and St. Louis bootleggers. These “dives” offered gambling as well as liquor. According to Clark, a student won $600 in one establishment and lost it in another![17]

Clark considered the automobile to be a significant promoter of drinking, “social immorality,” and bad scholarship as well as “a great time and money waster,” and, as a result, he sought to severely restrict car usage among students.[18] By the mid-1920s there were at least 148 student cars in the campus area, most owned by fraternities; less than a decade before, very few students owned autos, and it was possible “to amble, not car-dodge, across Wright Street.”[19] As early as 1923, Clark wrote to President Kinley expressing alarm at the increasing number of cars on campus and saying that he wished “none of our students here had automobiles.”[20]

Clark got his way in 1926 when the Council of Administration imposed a student car ban. The ban wasn’t total: exceptions were granted “in cases of proved necessity.”[21] For example, Garland Grange, Red’s brother, received permission to drive his car home to Wheaton on weekends. The Council, however, granted Grange’s request only reluctantly since “the student who goes home at week-ends finds it almost impossible to do good college work,” Clark explained.[22]

References

[1] Daily Illini, 23 October 1930; 18 May 1926.

[2] Walter Deuel to Thomas Arkle Clark, 2 May 1929, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 47, F: Deuel, University of Illinois Archives.

[3] Daily Illini, 21 December 1927.

[4] Ibid., 18 May 1926.

[5] Lynn Montross and Lois Seyster Montross, Town and Gown (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1923), 186-87.

[6] Daily Illini, 15 February 1921.

[7] Ibid., 18 May 1926.

[8] Ibid., 23 October 1930.

[9] Ibid., 24 October 1930.

[10] Arthur Lumbrick to David Kinley, 27 July 1922, David Kinley General Correspondence (2/6/1), B: 62, F: LO-LY, University of Illinois Archives.

[11] Eugene Davenport to Arthur Lumbrick, 28 July 1922, ibid.

[12] Logan Peirce to Nina Ruth Harding, 27 November 1923, Nina Ruth Harding Papers (41/20/155), B: 2, F: Nov. 27, 1923-Sept. 30, 1924, University of Illinois Archives.

[13] Daily Illini, 18 May 1926.

[14] Thomas Arkle Clark to David Kinley, 10 February 1921, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 24, F: Kinley.

[15] Clark to Kinley, 17 November 1921, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 28, F: Kinley.

[16] Urbana Daily Courier, 26 May 1927.

[17] Thomas Arkle Clark to Council of Administration, 21 February 1928, Council of Administration Minutes (3/1/1), Volume 29, University of Illinois Archives.

[18] Thomas Arkle Clark to David Kinley, 24 October 1923, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 34, F: Kinley.

[19] Illinois Alumni News, December 1925.

[20] Clark to Kinley, 24 October 1923, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 34, F: Kinley.

[21] Daily Illini, 15 July 1926.

[22] Thomas Arkle Clark to Garland Grange, 4 February 1927, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 42,

Further Resources

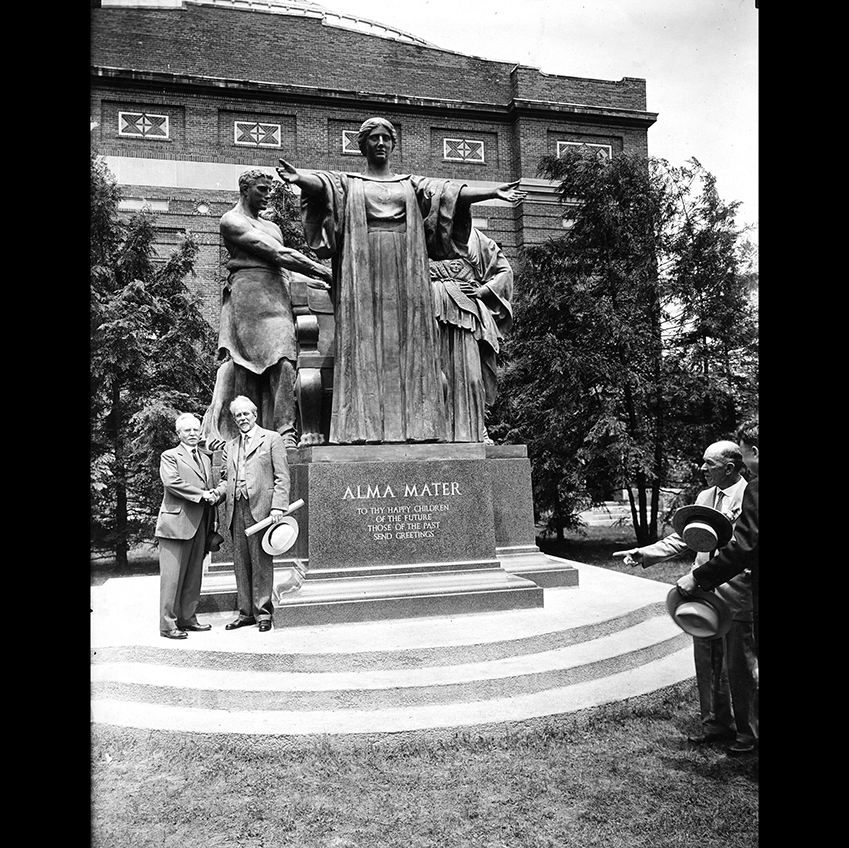

![]()

Traditions & Sports

Old traditions like the May Fete and Interscholastic Circus started fading in the 1920s as students preferred to see movies, listen to radio, shop, and attending sporting events. Class gifts continued, however, including sponsorship of Lorado Taft’s Alma Mater statue.

Homecoming also remained wildly popular, especially due to football coach Robert Zuppke’s three Big Ten Titles and presence of star player Red Grange. It was Grange’s phenomenal performance in October 1924, in fact, that put college football on the national map. He was not the only sports phenomenon, however. Student Harold Osborn won gold medals in decathalon and high jump at the 1924 Paris Olympics, shattering world records.

With the rise of consumer culture and modern mass entertainment in the 1920s, students–like most everyone else–began spending much of their free hours shopping, watching motion pictures, listening to radio shows and records, attending sporting events, and reading the latest best-sellers. Busy doing other things, students had less time to devote to traditional U of I activities. Perhaps not surprisingly then, such long-running University traditions as the May Fete and the Interscholastic Circus started sliding toward oblivion.

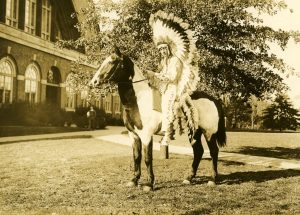

Not all was bleak on the tradition front, however. Homecoming–the University’s preeminent tradition—remained exceptionally popular, becoming increasingly “pretentious,” and reached a peak of sorts in 1924 when some 67,000 spectators at the new Memorial Stadium watched Harold “Red” Grange gallop into history against Michigan.[1] Continuing the long tradition of senior gifts, five thousand alumni from the classes of 1923 through 1929 as well as others helped make Lorado Taft’s “Alma Mater” a reality.[2] “I have always had a desire to personify the college which is so dear to my boyhood,” Taft confessed in a 1929 letter. “All through life I have retained a romantic love for my Alma Mater and have long been dreaming of this group.”[3] Also, several new traditions were launched in the 1920s: Dad’s Day in 1920; Mom’s Day in 1921; and Chief Illiniwek in 1926.[4]

Usually occurring in the early spring or after a great athletic victory, the student celebration or “riot” was one tradition that University officials hoped would go away. During these “celebrations”—first held during the James administration—groups of students brandishing guns, horns, cow-bells, whistles, and the like marched on downtown Champaign and stormed theater doors there, attempting to get inside for a free show.[5] A crowd of thousands–made up of U of I students, high schoolers, grade schoolers, and “a large collection of citizens of all ages”–turned out for the 1926 “spring celebration” when the Virginia Theatre was besieged with stones and bricks. Repulsed at the Virginia, the marchers then advanced on the Orpheum but were beaten back by policemen wielding billy clubs and blackjacks.[6] “Bloody noses, black eyes, and lacerations caused by blackjacks were more numerous last night than in spring celebrations of the past three years,” the Daily Illini noted. Seven people were injured in the melee, and nearly fifty students were put on probation for their role in the “celebration.”[7]

Back in the autumn of 1912, George Huff had ended an earlier student “riot” by making “the most impassioned speech ever heard from the lips of the veteran athletic director.” “If you want to kill football,” Huff declared to the students, who were celebrating a football victory, “this is the way to do it; you’re killing it now. There has been talk of abolishing football here because of just such things as this . . .”[8] Football of course wasn’t abolished, and Huff’s hiring of Robert Zuppke not long after this speech paved the way for Illini football’s “golden age” in the 1920s. Under Coach Zuppke, 1920’s-era Illinois teams won or shared three Big Ten titles and claimed the national championship twice, in 1923 and 1927.[9] The new Memorial Stadium greatly contributed to the success of Illini football in this period. “A gift of the alumni and people of Illinois, the stadium was the key factor in the ‘golden’ era of Illinois football,” archivist and historian Maynard Brichford wrote. “From 1923 to 1930, football began producing substantial profits on the field, in the grandstands and in the accounting office.”[10]

On the warm Homecoming afternoon that Memorial Stadium was officially dedicated, junior Harold “Red” Grange scored five touchdowns on the ground (and threw a pass for a sixth) against a heavily favored Michigan team. Grange’s phenomenal performance that day—October 18, 1924– helped put college football on the national map and turned the newly built Memorial Stadium into an instant historic landmark.[11] Grange turned pro after the 1925 season, signing a contract with the Chicago Bears. Coach Zuppke lamented Grange’s departure. “My main regret,” Zuppke told a crowd, “is that Grange will no more finish University than the Kaiser will go back to Germany.”[12]

Dean of Men Thomas Arkle Clark may have been one of the only Illini not sorry to see “Red” go. In early 1925 Clark had chastised Grange for missing two many classes. “I should say within the last year you have been absent almost one-third of the time,” the dean wrote. “You can’t do this any longer and get by with it, for you are gradually slipping.”[13] The following autumn, President Kinley himself intervened in the situation, telling Grange it was “imperative that you get back into your classes at once in order to avoid being dropped for cutting.”[14] Shortly after Grange left the University, Clark unburdened himself in a December 4, 1925, letter to William Lodge, president of the Dads’ Association. “It seems to me the wisest thing to make no comment at all,” the dean asserted, “but simply to hope that the time will come when Red will appreciate what has been done for him by his friends who have furnished him money on which to go to college, by the University authorities who have borne with his irregularities and who have given him more consideration than all the other members of the team combined, and by his team mates who made it possible for him to attain the popularity and the distinction which are his.” Clark continued: “No one knows better than you that Red has been a very serious problem to us all, especially the last two years. Though I would be the last to criticize him publicly, and have not done so, I think it would be foolish to commend him.”[15]

Harold Marion Osborn was another stand-out Illinois athlete in the 1920s. The product of a central Illinois farm family, Osborn attended the University from 1919 until 1922. An exceptional all-around athlete, he helped Harry Gill’s track team capture both the indoor and outdoor Big Ten titles three years in a row. In the 1924 Paris Olympics Osborn won gold medals in both the decathlon and the high jump, breaking Olympic records in the process. His victory in the decathlon shattered a world record as well and gained for him renown as “the world’s greatest athlete.” He would win 17 national titles and set six world records during his career. In 1974 he was inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame along with Jesse Owens, Babe Didriksen Zaharias, Bob Mathias, and Wilma Rudolph.[16]

References

[1] John Franch, “Illinois Homecoming: A Century of Spirit,” Illinois Alumni 23 (Fall 2010), 22.

[2] Daily Illini, 18 September 1932.

[3] Muriel Scheinman, “Labors of Love: Lorado Taft—the Sculptor behind the ‘Alma Mater’–Embraced Both His Art and His University, Illinois Alumni 22 (March 2010).

[4] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 9, 13, University of Illinois Archives; ibid., Chapter 10, 39-40.

[5] Ibid., Chapter 6, 35.

[6] Thomas Arkle Clark to David Kinley, 22 March 1926, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 40, F: Kinley, University of Illinois Archives.

[7] Daily Illini, 19 March 1926.

[8] Ibid., 20 October 1912.

[9] Maynard Brichford, Bob Zuppke: The Life and Football Legacy of the Illinois Coach (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2008), 72-73.

[10] Ibid., 72.

[11] Franch, 22.

[12] Daily Illini, 24 November 1925.

[13] Thomas Arkle Clark to Harold Grange, 27 February 1925, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 36, F: Gr-Gu.

[14] David Kinley to Harold Grange, 14 November 1925, ibid., B: 40, F: Kinley,.

[15] Thomas Arkle Clark to William Lodge, 4 December 1925, ibid., B: 40, F: Kl-Lo.

[16] Harold Osborn Papers