A child of the Morrill Act, the University of Illinois began life in 1867 as the Illinois Industrial University: the school’s radical mission was to extend higher

education to members of the working-class. With too few students and too little money, the University languished for years in obscurity. Near the end of the century, the students and alumni helped give the school a new start, and the U of I moved forward under the leadership of Thomas J. Burrill and Andrew Draper. A skilled administrator, Draper placed the University on a firm foundation. His successor would take the U of I to the next level.

Related Links

![]()

Administration

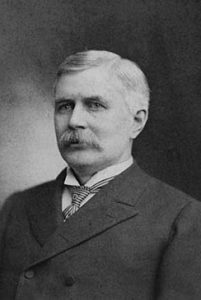

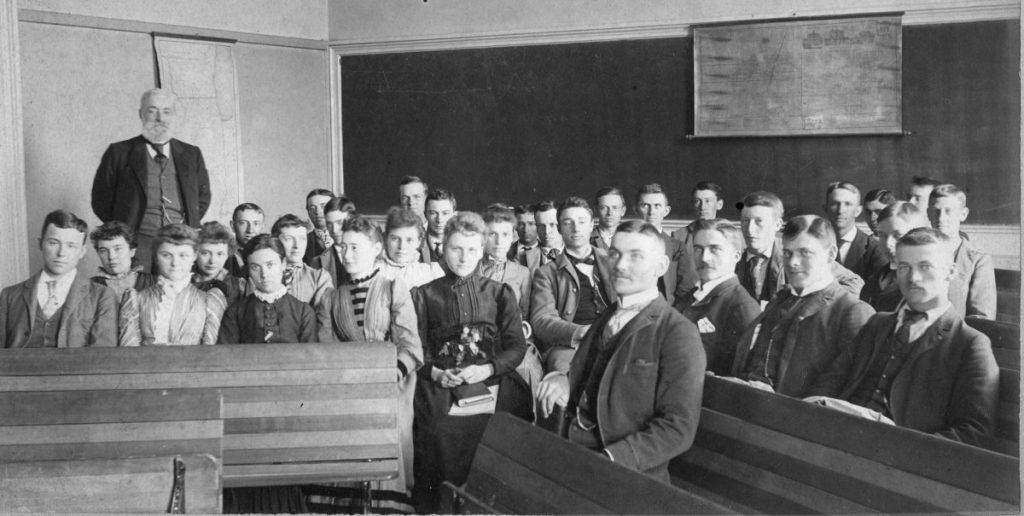

The first regent, John Milton Gregory, championed liberal arts, freedom of electives, and student self-government, which students appreciated. He later turned authoritarian, however, causing a student rebellion in 1880 to force his resignation. His successor, another harsh disciplinarian who also opposed intercollegiate athletics and secret societies, met a similar fate in 1891.

In light of student revolts, Acting Regent Thomas Burrill abolished the demerit system and compulsory chapel, allowed fraternities and athletics, restored elective freedom, improved the status of professors, and started the Graduate College. His successor, Andrew Draper, with support from the Illinois governor, tripled student enrollment, embarked on an ambitious campus building plan, and created the schools of Pharmacy, Dentistry, and Medicine.

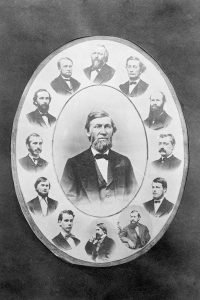

Faculty 1886:

1. William McMurtrie, Chemistry

2. Kittie M. Baker, Music

3. James H. Brownlee, Rhetoric and Elocution

4. Edward Snyder, Modern Languages

5. George E. Morrow, Agriculture

6. James Crawford, Librarian

7. Arthur N. Talbot, Municipal and Sanitary

8. Stephen Forbes, Zoology

9. Peter Roos, Drawing

10. Helen B. Gregory, English

11. Samuel Shattuck, Business Manager and Prof. Mathematics

12. President Selim Peabody

13. Joseph C. Pickard, English

14. N. Clifford Ricker, Dean of the College of Engineering

15. Thomas J. Burrill, Botany

16. Charles W. Rolfe, Zoology

17. Theodore B. Comstock, Physics

18. Donald McIntosh, Veterinary

19. Baker, Civil Engineering

20. Charles McClure, Commandant

21. Arthur T. Woods, Mechanical Engineering

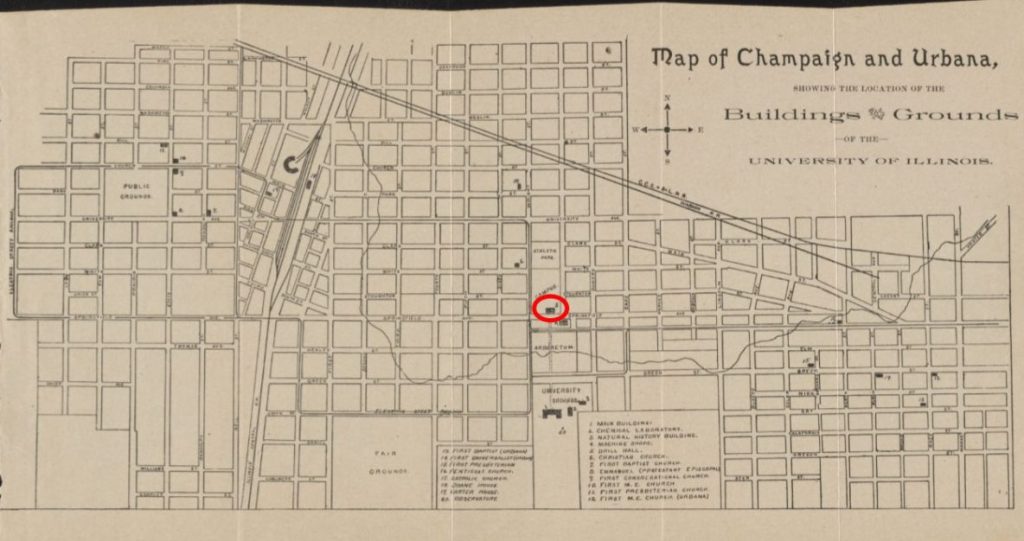

Buildings:

A. Wood Shops and Drill Hall

B. Chemistry (now Harker Hall)

C. University Hall

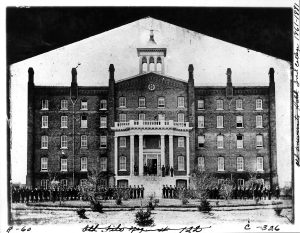

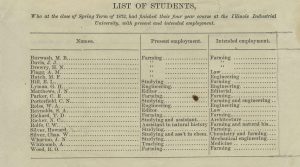

The University’s beginnings were modest. On March 2, 1868, some fifty men passed through the doors of the five-story University Building–“The Elephant,” as it was popularly known—to enroll on the school’s first day.[1] A decade later there were only 377 students at the University. The school would not surpass the 500-student mark until 1890. Money also was in short supply: state appropriations remained flat until near the end of the century.[2] The “bucolic school in the interior” failed to generate much interest in the state. Even as late as 1894, the Chicago Herald could say that there was no such thing as the University of Illinois.[3]

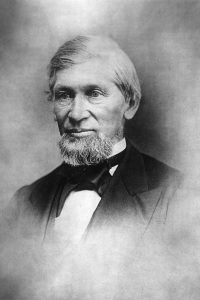

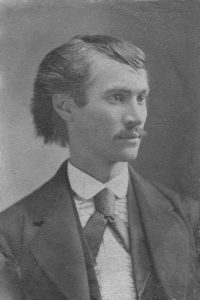

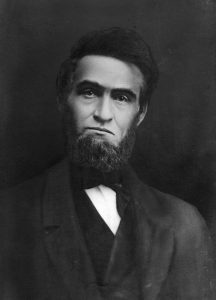

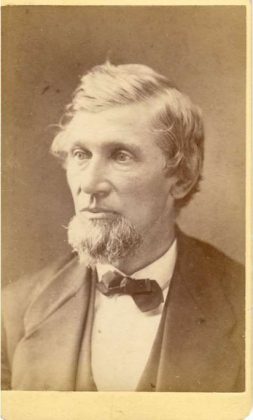

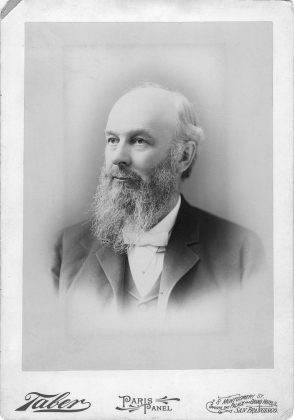

John Milton Gregory led the University during its earliest years of struggle. A Baptist minister and former Michigan educator, the bespectacled and bearded Gregory championed liberal arts education, freedom in the choice of courses, and student self-government. Opponents derided Gregory for his liberal policies, but the students respected him. Indeed, in later years, alumni from the Gregory period distinguished themselves from other classes by calling themselves “Gregorians.”[4] But, in the late 1870s, the students began to lose a measure of esteem for Gregory, apparently in part because of his “unseemly” behavior while courting the much younger Louisa Allen, a Domestic Science professor who he married in 1879. He reportedly was observed “hanging over banisters, or in the corridors of the University Building holding long conversations with Miss Allen,” and was said to take “the back way” to Allen’s boarding house, skulking around trees to get there[5].

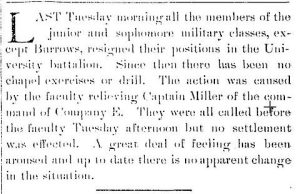

Gregory ultimately assumed a more authoritarian tone against the students, and his popularity plummeted. A military rebellion helped force his resignation in 1880.[6] Selim Peabody, Gregory’s successor, suffered a similar fate. Never a well-liked figure, the cold and aloof Peabody adopted policies that made him even more unpopular: he tightened admissions standards, did away with elective freedom, and imposed a widely hated demerit system.[7] Perhaps more importantly, he strongly opposed intercollegiate athletics and secret societies—the two bulwarks of an emerging student culture. In 1891 a cadet rebellion–aided and abetted by Chicago alumni–helped usher Peabody out the door.[8]

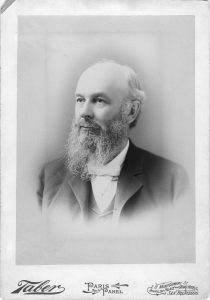

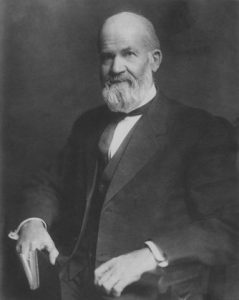

The students had prevailed in a struggle pitting “the ideal of discipline” against “the ideal of freedom,” in historian Winton Solberg’s words.[9] Recognizing the new reality, Acting Regent Thomas J. Burrill, a long-time Botany professor, implemented sweeping reforms: the demerit system was scrapped, compulsory chapel was ended, fraternities were tolerated, and intercollegiate athletics was encouraged. On the academic front, Illinois launched a Graduate School, improved the status of professors, established extension courses, and restored elective freedom.[10] Burrill’s reforms set the U of I on the path to becoming a modern university.

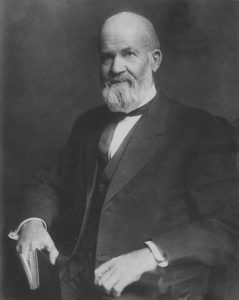

Andrew Draper continued to move the University forward. An expert educational administrator, the tough-minded Draper concerned himself with the material development of the University. Under Draper, student enrollment (at Urbana-Champaign) more than tripled, going from 810 in 1894-5 to 2,674 in 1903-4, the number of buildings jumped from six to 27, and state biennial appropriations swelled, rising from $594,938 in 1895-6 to $1,814,863 in 1903-4.[11] At the beginning of his administration, Draper secured the invaluable assistance of John Peter Altgeld, the first Illinois governor to take a real interest in the University.[12] Draper also helped give the U of I a foothold in Chicago where schools of Pharmacy and Dentistry and a College of Medicine were established.[13] According to the historian Allan Nevins, the University finally “found itself” under Draper.[14]

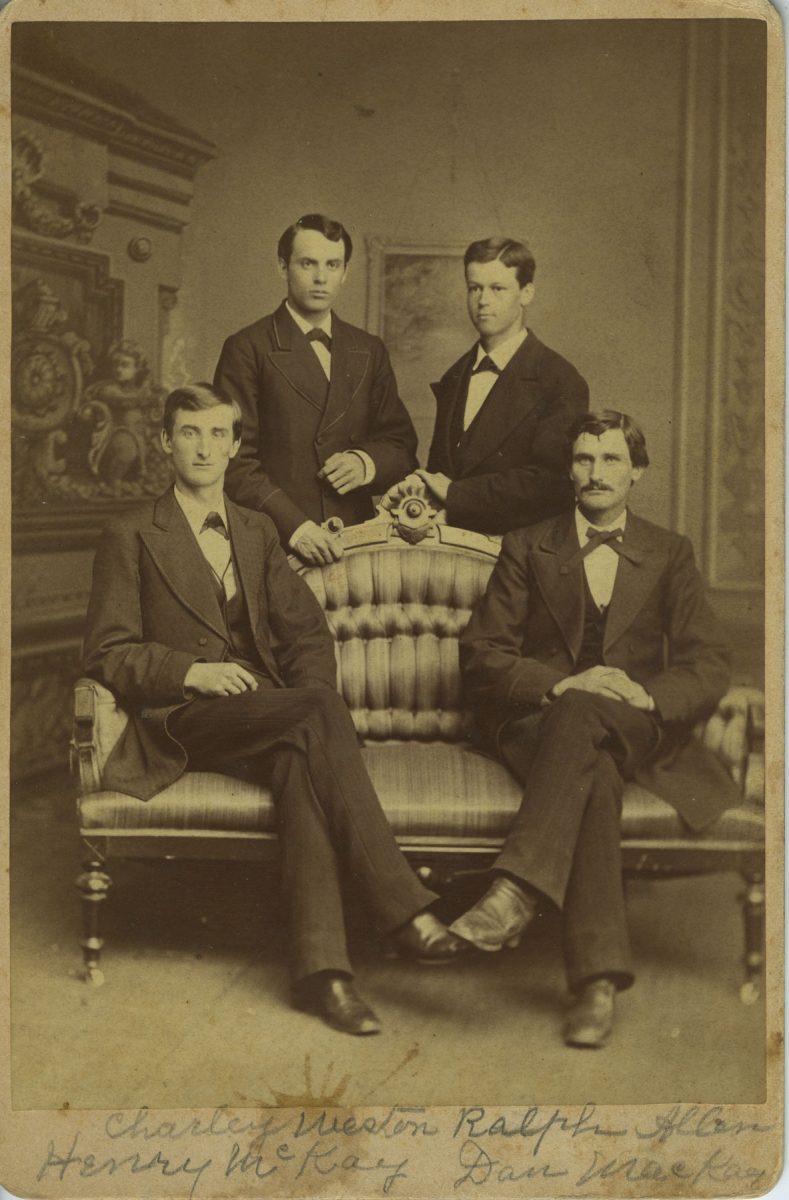

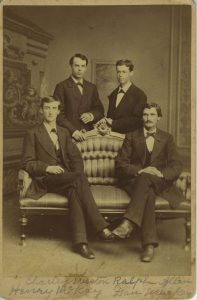

The students deserve much of the credit for the University’s progress during these early years. They took it upon themselves to boost the fortunes of their fledging little school on the prairie. “I think we all have the I. I. U’s prosperity at heart,” undergraduate Ralph Allen wrote a friend in 1875, “and we all know that the success of the university largely depends upon the students.”[15] This was not an idle boast. In 1878 the students and alumni compelled the University to issue degrees to graduates rather than mere certificates; in 1885 they successfully lobbied to change the University’s name; in 1887 they helped make the Board of Trustees an elective body.[16] It was the students who pushed Gregory and Peabody out.

Looking back on his role as a student activist in the rebellion against Peabody, Charles Kiler was unapologetic. “Let it be recorded that it was the student body that dreamed visions of a great future,” Kiler wrote in 1916. “ . . . We did not simply want to dance and join frats, to play ball and have a good time in general—we wanted a much greater and bigger thing. We wanted a chance to grow and develop as other state institutions were growing. We wanted to be in shape to compete in every way with the other institutions in the middle west who were our natural competitors.” Kiler credited the classes of his era for giving the University “the kick that sent it on its way to bigger things.”[17]

References

[1] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois, 1867-1894: An Intellectual and Cultural History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1968), 99.

[2] Allan Nevins, Illinois (New York: Oxford University Press, 1917), 359.

[3] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904: The Shaping of the University (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 14.

[4] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 2, 31, University of Illinois Archives.

[5] [J. E. Stark] to Allan Nevins, 1916 May 20, Carl Stephens Papers (26/1/20), B: 10, F: Early Days, Ibid.

[6] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1867-94, 207-13.

[7] Ibid., 318.

[8] Ibid., 318-26.

[9] Ibid., 325.

[10] Ibid., 343-344, 373-381.

[11] Nevins, 359.

[12] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 10-12.

[13] Ibid., 392.

[14] Nevins, 153.

[15] Ralph Allen to “Friend Dan,” 26 December 1875, Allen Family Papers (41/20/21), B: 2, F: Letters, 1875, University of

Illinois Archives.

[16] Solberg, University of Illinois 1867-1894, 164-65, 225-31.

[17] Charles Kiler to Allan Nevins, 16 June 1916, Carl Stephens Papers (26/1/20), B: 10, F: Early Days, University of Illinois

Archives.

Further Resources

![]()

Academics

“Let us but demonstrate that the highest culture is compatible with the active pursuit of industry.” – John Milton Gregory

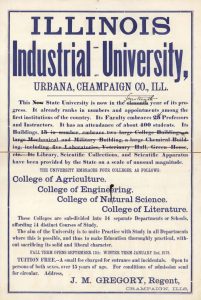

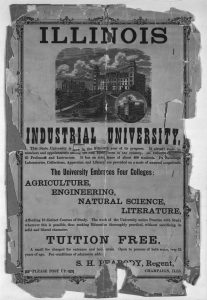

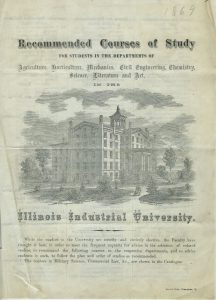

From the beginning, the new Illinois Industrial University had a split personality. The Morrill Act expected a college devoted to agriculture and the “mechanical arts” rather than traditional liberal arts. The first regent, John Milton Gregory, however, insisted on combining the practical with the classical, leading to creation of not only an engineering college, but colleges and schools dealing with literature, natural science, commerce, domestic science, library science, and several more.

There were 351 faculty by century’s end, including pioneering botanist Thomas Burrill; Stephen Forbes, founder of the science of ecology; agronomist Cyril G. Hopkins, whose experiments revolutionized agriculture; and Isabel Bevier, a pioneer in household science.

The Morrill Act of 1862 gave federal land to the states to be used to underwrite the costs of building and endowing colleges—but not just any colleges. The act specifically called for the establishment of a new kind of college where “the leading object shall be, without excluding other scientific or classical studies, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts.” (The act also required military training.)[1] Certain zealous proponents of so-called industrial education like Jonathan Baldwin Turner—whose fierce terra cotta image graces the southern façade of Lincoln Hall—wanted the new Illinois Industrial University to steer completely clear of the old-fashioned classical subjects–rhetoric, grammar, logic, literature, Latin, etc.–long taught in the Eastern colleges they so despised.

“What the State wants is not a one-horse classical school, in which the tedium of scanning Latin verse is relieved by occasional incursions into the domain of Agriculture and other branches of Natural Science,” the Chicago Tribune declared in 1867, expressing the views of Turner and others.[2](Dec. 1, 1867) No, the mission of the school was to teach the students “how to win bread and butter,” the Tribune argued, and agriculture, engineering and the sciences should be the only subjects taught.[3]

John Milton Gregory, the University’s new regent, begged to differ. A Baptist minister, Gregory hoped to combine the practical and the classical, labor and learning. “Let us but demonstrate that the highest culture is compatible with the active pursuit of industry,” he asserted in his inaugural speech.[4] Gregory’s ideas were not well-received by the supporters of industrial education, including farmer Matthias Dunlap, a member of the Board of Trustees. Dunlap regularly used his Chicago Tribune column to attack Gregory, who he called “a mere speech maker, a man ignorant of agricultural practice and science.”[5] The Legislature weighed in on this controversy in 1873 when it required all of the University’s undergraduates to study “such branches of learning as are adapted to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions of life.”[6] Perhaps not surprisingly, the College of Engineering came to dominate the campus during this period; by 1894, over one-half of the school’s 604 undergraduates were in Engineering, and the College ranked fourth in size in the nation.[7]

Besides Engineering, there were, by 1872, colleges of Agriculture, Natural Science, and Literature and Science, and schools of Commerce, Military Science, and Domestic Science and Arts.[8] In the 1890s and early-1900s, the University would add schools of Music and Library Science, a Graduate School and a College of Law, and, in Chicago, schools of Pharmacy and Dentistry and a College of Medicine.[9] Gregory had established an elective system, so early students were free to enroll in whatever College’s courses interested them.[10] Regent Peabody later scrapped the elective system, replacing it with a rigid program of study.[11]

To improve the quality of its prospective students, the University began in the 1870s to inspect high schools, accrediting those that met its standards. Students graduating from an accredited high school could enter the University without taking the admissions exam. (The admissions exams tested one’s knowledge of arithmetic, grammar, geography, spelling, and history, and most of the questions are real stumpers for the modern American.) In 1876 the University also started offering a year of introductory course work for those who had failed the entrance exams; this program eventually developed into a full-fledged Preparatory School. In 1879-80, 131 out of 434 students in the University were enrolled in this preparatory program.[12]

The faculty grew slowly during the Gregory and Peabody years, from four in 1867-8 to 39 in 1890-1, Peabody’s last year. The numbers began to pick up during the Burrill regency and really grew during the Draper presidency: in Draper’s final year at the helm of the U of I, there were 351 faculty members.[13] The University was fortunate to have had some exceptional professors during its early years of struggle: botanist Thomas Burrill, the pioneering plant pathologist who discovered bacteria could cause plant disease; Nathan Clifford Ricker, the first American graduate of a university architecture department and the force behind the first Architectural Engineering program in the U. S.; Stillman Robinson, who combined workshop practice and theory to train Engineering students; Louisa Allen, creator of the first “high-grade” domestic science course in the country; naturalist Stephen Forbes, a founder of the science of ecology; agronomist Cyril G. Hopkins, whose experiments on soil fertility and corn breeding revolutionized agriculture; Eugene Davenport, who almost single-handedly revived the moribund College of Agriculture; Katharine Lucinda Sharp, founding director of the School of Library Science; and Isabel Bevier, a pioneer in household science.[14]

References

[1] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois, 1867-1894: An Intellectual and Cultural History (Urbana: University

of Illinois Press, 1968), 57.

[2] Chicago Tribune, 1 December 1867.

[3] Ibid., 18 December 1867.

[4] Solberg, 101.

[5] Quoted in Allan Nevins, Illinois (New York: Oxford University Press, 1917), 365.

[6] Solberg, 115-16.

[7] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904: The Shaping of the University (Urbana: University of

Illinois Press, 2000), 156.

[8] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1867-1894, 104.

[9] Ibid., The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 392.

[10] Ibid., The University of Illinois 1867-1894, 110.

[11] Ibid., 232.

[12] Ibid., 130-31.

[13] Nevins, 359.

[14] For biographies of these faculty figures, see Winton Solberg’s two books on University of Illinois history

Further Resources – Faculty Papers

![]()

Campus Architecture & Planning

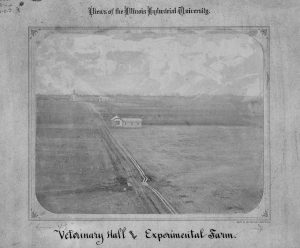

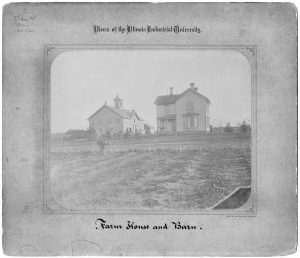

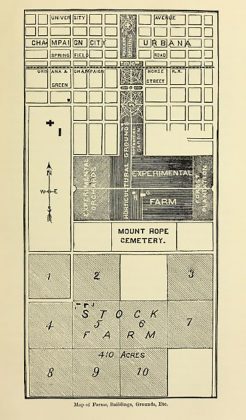

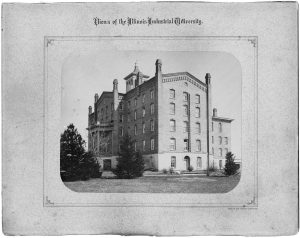

Why is the U of I in the flattest part of Illinois? Many claimed bribery had a hand in the decision. The school’s first building, the five-story “The Elephant,” likewise was shoddily built by land speculators.

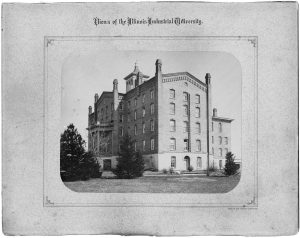

Regent Gregory, not surprisingly, quickly saw the need for new buildings and placed them along and south of Green Street, including Harker Hall, the Natural History Building, Engineering Hall, and Altgeld Hall. President Draper’s siting of Davenport Hall in a more central location created the east boundary of the Main Quad. Several more buildings in that area quickly followed. Many were designed by alumni and are now on the National Register of Historic Places. The Early Years Building Tour: 1867 – 1904

In the 1850s the theologian Horace Bushnell spent several months carefully searching for a suitable site for a proposed California university. “The site of a university is to be chosen but once,” Bushnell explained. “Once planted, it can never be removed; and if any mistake is made, that mistake rests on the institution as a burden to the end of time.” It all comes down to “location, location, location,” as the real estate professional would say. And the location of the new Illinois Industrial University was anything but ideal: a flat, muddy, nearly treeless prairie located midway between two rural hamlets populated by some 8,000 souls.

Opponents charged that the Urbana-Champaign lobbyists had secured the location through legislative chicanery, including bribery. No less a figure than Jonathan Baldwin Turner, the apostle of industrial education and a supporter of the Jacksonville bid, claimed that the “Champaigners” purchased the votes of “the miserable scamps and scalawags” using “promises of office or lots of cash.” (Or, in some cases, not so much cash: Turner reported hearing that some legislators sold their votes at a mere “twenty-five dollars a head.”)

Whatever the truth of these allegations, Champaign County won out, and the new Illinois Industrial University ended up “in the flattest, plainest, most monotonous section of Illinois,” in the words of historian Allan Nevins. The sole building on the nascent campus was dubbed “The Elephant”–short for “White Elephant”–a five-story brick building 125-feet across and 40-feet deep with a smaller four-story wing. Serving as a dormitory as well as a classroom/office building, the 181-room structure would in effect be the University for its first dozen years.

The ten acres of bleak, nearly featureless prairie surrounding “The Elephant” constituted the main campus in these early years; later Illinois Field would be located here and, much later, the Beckman Institute. The University also owned a 160-acre tract about a half mile south of the main campus and another 405 acres south of Mount Hope Cemetery. These unconnected checkerboards of land did not include what ultimately would become the University’s central campus—the area that includes the Main Quad. But showing foresight, the board of trustees quickly acquired this strip of 36.6 acres stretching for one-mile south of the ten-acre Elephant tract. This historic land purchase was approved November 26, 1867, and the University launched itself on a course of southward expansion that continues today.

“The Elephant” had been shoddily built by land speculators hoping to make a quick buck, and its inadequacy rapidly became evident. So the trustees requested and the Illinois Legislature appropriated money for two new buildings: a mechanical hall and a new main hall. The decision where to locate this new structure proved to be crucial: the future of the campus’s physical development was at stake. Several trustees wanted the new building—the future University Hall—to be north of Springfield Avenue on land to be purchased east of the Elephant tract. But Gregory boldly called for a location far south of the present campus, south even of distant Green Street, on a ridge smack dab in the middle of the horticultural “garden.” Gregory’s motion prevailed in a contentious Board of Trustees vote. This decision forever shifted the University’s center of gravity southward. Unlike his many critics, who feared the University Hall site was “so far south that the University would never grow up to it,” Gregory had great faith in the future.

No definite plan determined the locations of the small number of buildings constructed in the early years. During that period, “the only plan apparent for the campus development was to line up the buildings along Green street,” James White, the long-time Supervising Architect, wrote. Indeed, Harker Hall, the Natural History Building, Engineering Hall, and Altgeld Hall were all located near Green Street. The Kenney Gym Annex ended up on Springfield Avenue—a site apparently chosen by Selim Peabody, John Milton Gregory’s successor, who lacked Gregory’s aesthetic sensibilities.

But there was no more campus real estate available on Green Street after the completion of Altgeld Hall in 1897: Any new buildings would have to be sited somewhere else. At this key point a real campus plan would have helped, but instead Andrew Sloan Draper, the University’s hard-charging fourth president, improvised. Acting as the autocrat he tended to be, Draper unilaterally decided the new Agriculture Building (Davenport Hall) should be placed south and east of University Hall. The decision turned out to be inspired. The location of Davenport Hall—the first piece of the puzzle—would determine where other buildings would be constructed on the central campus, beginning with the Chemistry Laboratory (Noyes Laboratory) in 1902. Davenport Hall also delineated the east boundary of what would become the University’s iconic Main Quad.

Between the founding of the University in 1867 and the end of Draper’s presidency in 1904, the number of major and minor buildings on campus jumped from one to twenty-seven. Some of these structures were designed by alumni (Engineering Hall, by George Wesley Bullard, ’82; Davenport Hall, by Joseph Corson Llewellyn, ’77; Noyes Lab, by Nelson Strong Spencer, ’82), but the major player in early University architecture was Nathan Clifford Ricker. A pioneering Architecture professor and long-time College of Engineering dean, Ricker designed five iconic campus buildings: the future Harker Hall, the future Kenney Gym Annex, the Natural History Building, the Metal Shop (demolished in 1993), and the future Altgeld Hall. All of the surviving Ricker buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A modest man, Ricker apparently did not think very highly of the icons he designed.[1] In 1910 he boldly proposed the creation of an entirely new campus south of the Auditorium and called for the eventual removal of the old campus buildings—including, amazingly, his own.

References

[1] Information for this unit came from Lex Tate and John Franch, An Illini Place: The Campus of the University of Illinois (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, forthcoming).

Natural History 1894, 3D model – University Sesquicentennial Celebration

Further Resources

Diversity

Diversity

The University’s earliest students were mostly white, of European descent, Protestant, and from adjacent counties. By 1873, however, there were students from 69 counties,12 states, and four foreign countries. By 1903, it was 12 foreign countries.

The first African-American student arrived in 1887, but numbers remained low, with only 10 enrolled between 1894-1904. One, Albert R. Lee, became the University president’s long-time chief clerk. An African-American also was elected to the Board of Trustees in 1873 but was driven out by “Repbulican ostracism.”

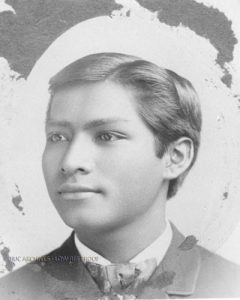

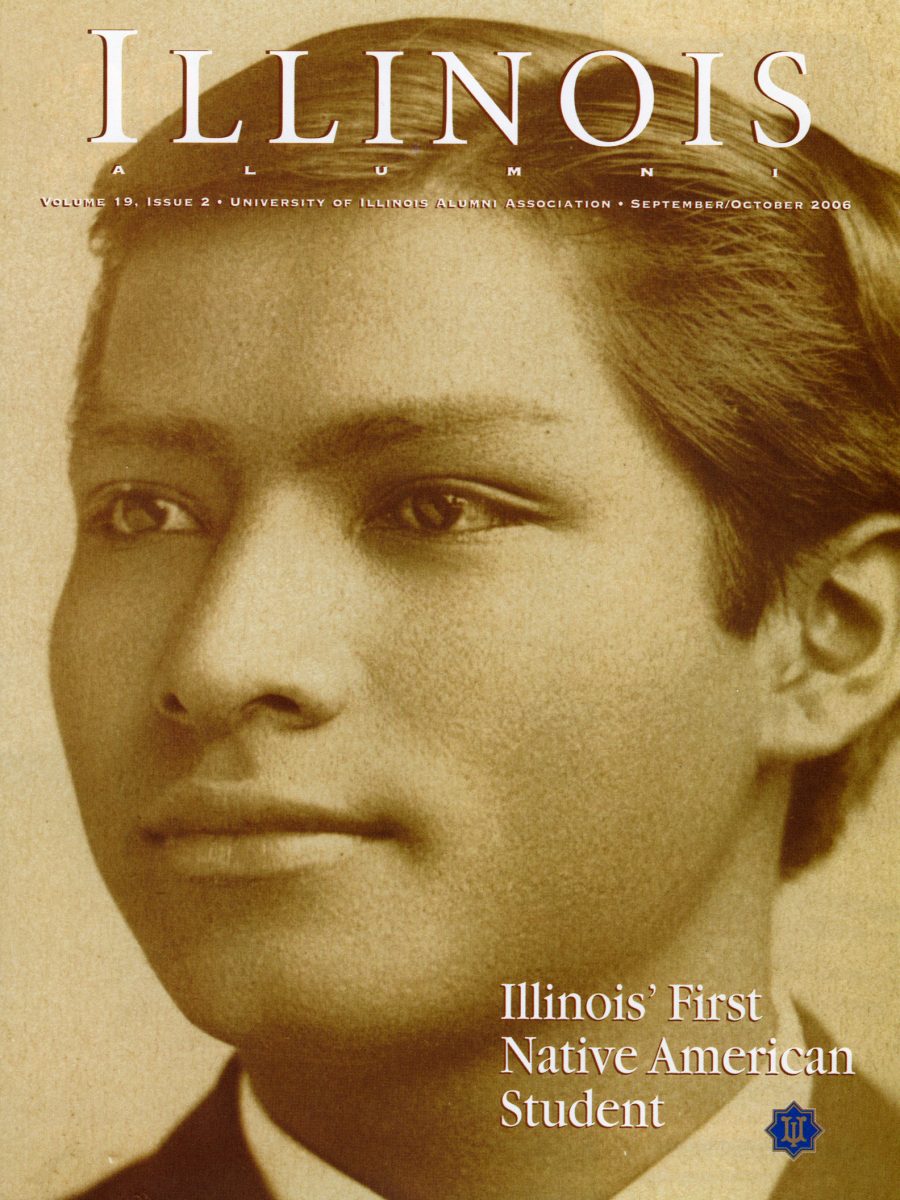

Carlos Montezuma was the first Native American graduate, in 1884. Elected class president, he became a physician and advocate for Native American rights.

The University’s earliest students were mostly white, of European descent, and Protestant, with Methodists, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists especially well represented.[1] At first they came primarily from the small towns and farms of Champaign and adjacent counties. Alumnus Charles Kiler described the members of his Class of 1892 as looking like they “had been born between two rows of corn.”[2] The pioneering students were often poorly educated, a reflection of the era’s inadequate school system: in 1868 there were only 108 public high schools in the entire state of Illinois and just one in Chicago.[3] According to historian Winton Solberg, their outlook on life tended to be a narrow one. “Their horizons were bounded by Protestant certainties, Fourth-of-July democracy, crude manners, and aesthetic unawareness,” Solberg wrote.[4]

Already, by 1873, the student body had become somewhat more diverse. That year students hailed from 69 different Illinois counties, twelve states, and four foreign countries: Japan, Turkey, Germany, and Greece.[5] Members of the Class of 1874 included Gregory Gabrialial Dabraskian, of Turkey, and Panagiottis Gennadius, of Greece; Gennadius would go on to become a respected botanist, agronomist, and government official.[6] By 1903-4, out of 1,480 undergraduates at the University, 732 came from central Illinois, 456 from northern Illinois, 97 from southern Illinois, 183 from out of state, and 12 from foreign countries.[7]

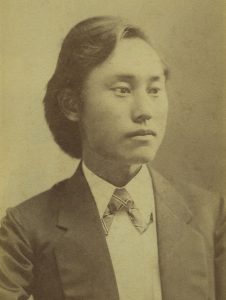

Not long after the Meiji Restoration opened up Japan to Western influence, Illinois received its first Japanese student, Tunetaro Yamaou, who attended in 1872-3.[8] Less than twenty years later, Sitsuro Yamada came to the U of I and stayed for two years (1888-90). Yamada belonged to the Adelphic Literary Society; his speech on “America and Japan” earned raves from the Illini. “His appearance was graceful, his gestures good, and at times he was really eloquent,” the Illini said of Yamada. “The oration was well worthy of praise.”[9] Shigetsura Shiga, who received a B. S. in architecture in 1893, was the first Japanese graduate of the U of I; he returned to his hometown of Tokyo where he worked as a professor and government architect.[10] In the 1920s Shiga served as president of the 75-member Japan Illini Club.[11]

The celebrated Carlos Montezuma was the University’s first Native American graduate. A member of the Yavapai tribe, Wassaja—Carlos’ birth name—had been abducted by Pima Indians in 1871 when only about five years old. After an amazing odyssey, Montezuma ultimately ended up at the Illinois Industrial University. He spent two years in the preparatory school before enrolling in the University itself. Montzuma earned the esteem of his classmates. A member of the Adelphic Literary Society, he won acclaim for his oratorical prowess, for his “mastery of a tongue not by any means a mother one to him,” and was elected president of the Class of 1884. After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry, Montezuma became a Chicago physician and gained renown as a champion of Native American rights.[12] The University has named the dormitory Wassaja Hall in his honor.

Very few African Americans attended the University in the early years. Jonathan A. Rogan, a freshman in civil engineering in 1887-8, seems to have been the first African American U of I student.

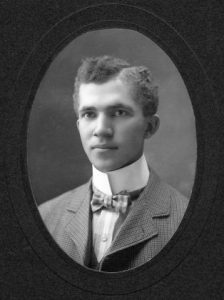

Between 1894 and 1904, ten African Americans enrolled at the University, including George Washington Riley, a member of the University Military Band who was “an artist on the snare drum” and who died in 1897 of typhoid fever, Albert R. Lee, who would become chief clerk in the President’s office and the unofficial “Dean of African American Students,” and William Walter Smith, the U of I’s first African-American graduate.[13]

Smith’s father had been a slave in Tennessee: in the 1870s he came to the Broadlands area in Champaign County and made a fortune in farming—at the time of his death in 1911 his estate was valued at $116,000 (roughly $3 million in today’s money).[14] Smith was a popular student, a member of the Illini, the rifle team, the YMCA, the Republican Club, and the Philomathean Literary Society.[15] Shortly after graduating in 1900, Smith “cast around for means of supporting” himself, not wishing to ask his father for “further aid”; he hit upon the idea of starting a students’ cooperative store at the University but failed to obtain President Draper’s support for the idea.[16] Earning a second degree from the U of I in 1907—a civil engineering degree–Smith spent time as the city engineer of Farmer City before embarking upon a career as a concrete specialist. He spent many years in South America where he built grain elevators and sold structural steel products.[17] He died in New York City in 1929.

An African American served as an early trustee of the University. John J. Bird, an accomplished Republican politician from Cairo, may have been the first African American trustee of a non-historically black American university. Newly elected Governor John Beveridge appointed the 29-year-old Bird, a Cincinnati native, to the Board of Trustees in 1873, apparently rewarding him for his political efforts in behalf of the state Republican Party.[18] Bird served on the Board until 1883. The Cairo Daily Bulletin claimed that Bird “was treated with great disrespect by the white members of the board because he was black, and was actually driven out of the board by Republican ostracism.” He nonetheless remained “faithful to the Republican party, for which he has done much service and from which he has received no kindness or reward.”[19] At the time of his death in 1912, Bird was working as a custodian in the Illinois statehouse.[20]

References

[1] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois, 1867-1894: An Intellectual and Cultural History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1968), 177-78.

[2] Charles Albert Kiler, On the Banks of the Boneyard (Urbana: Illini Union Bookstore, 1942), 23.

[3] Solberg, 130.

[4] Ibid., 168.

[5] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter 2, 26, University of Illinois Archives.

[6] The Alumni Quarterly and Fortnightly Notes, 5 (February-March 1920), 116.

[7] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois, 1894-1904: The Shaping of the University (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 48.

[8] Carol Huang, “The Soft Power of U. S. Education and the Formation of a Chinese American Intellectual Community in Urbana-Champaign, 1905-1954” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Illinois, 2001), 83.

[9] The Illini, 21 May 1888.

[10] Ibid., 9 January 1901.

[11] Ibid., 30 October 1928.

[12] John Franch, “Torn between Two Worlds: The Life of Carlos Montezuma,” Illinois Alumni 19 (September/October 2006), 22-26.

[13] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 48-49.

[14] Urbana Daily Courier, 3 January 1912.

[15] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 276.

[16] William Walter Smith to Andrew Draper (PDF) , January 1902, Andrew Draper General Correspondence (2/4/1), B: 17, F: Smith, University of Illinois Archives.

[17] The Semi-Centennial Alumni Record of the University of Illinois (Chicago: The Lakeside Press, 1918), 137.

[18] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1867-1894, 120.

[19] Cairo Daily Bulletin, 19 December 1883.

[20] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1867-1894, 120.

Further Resources

![]()

Women

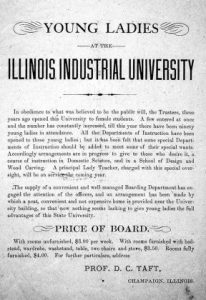

The first women were admitted to the University in 1870, subject to severe social restrictions and curfews. Regent Gregory himself paid for two houses to accommodate them. In 1874, he hired a “preceptress” to oversee women’s interests. She established a domestic science and calisthenics program. President Draper in 1897 hired the first Dean of Women as well as several notable women faculty.

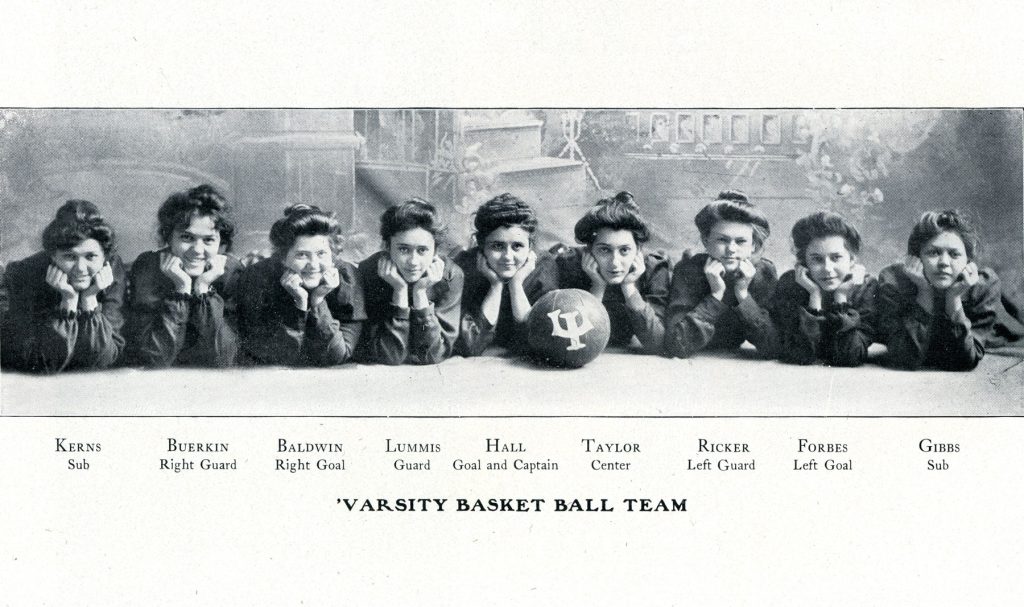

Women’s organizations now flourished, including the Young Women’s Christian Assocation (1884), Illinois’s first basketball team (1897—a women’s team, not men’s) and two sororities (1895), among others. A women’s gym was turned down, however, because it was thought inadvisable for women to do calisthenics.

In 1870, three years after the Illinois Industrial was founded, University the (all male) Board of Trustees agreed to admit women in a 5-4 vote, impending under restriction: Social life for women was restricted to weekends, chaperones were required for outings, and all female students had a midnight curfew unless permission from a faculty memb

er was given for a later curfew. Twenty-four women were admitted to the University in 1870, making the first class of co-eds the graduating class of 1874. In the earlier years, mostly local girls from the Champaign County area attended the university because at the time, few families were willing to send their daughters off to the university.[1]

John Milton Gregory was the first Regent of the university, and cast the deciding vote to admit women. Gregory was concerned about the housing needs of the female students, as there were no designated dormitories built yet. Gregory used his personal funds to provide two houses to accommodate them. The houses had unfurnished bedrooms, but offered well-appointed parlors and laundry facilities for the women at the rate of $3.00 a week. A matron with boarding school experience was hired to mind the women.[2]

On March 4, 1874, Gregory recommended hiring a “preceptress” to the Board of Trustees to oversee the female students of the university. Of the female students, he stated, “Their best interests demand that there shall be in the faculty a woman of high character and culture, who shall be specially charged with their oversight.”[3] He also suggested that “at the earliest day practical”, the Board of Trustees “provide for a School of Domestic economy and such other schools as the wants of our female students demand.”[4] And so Louisa Allen joined the faculty in 1874 to manage the interests of female students. In her six years as “preceptress” of the university, she established the groundwork for the first school for domestic science as well as a calisthenics program “in accordance with her belief that women should have strong bodies as well as strong minds.”[5] Allen married Regent Gregory in 1879 and the two left the university in a year later.

Lucy Flower was the first female Board of Trustees member, appointed in __, making her the first elected female official in the state. An extremely influential board member, she tactically motivated apathetic administration into accomplishing beneficial gains for the women of the university, such as hiring women faculty, creating a Woman’s Department and with it the official position of Dean of Women, building a Woman’s Building, establishing a formal Department of Household Science, and admitting women to the medical school.[6]

In 1897, “Andrew Sloan Draper—President and Regent of the university at the time—recommended the development of a new administration department titled “The Woman’s Department” directed by a newly appointment position known as “Dean of the Woman’s Department.”[7] Violet DeLille Jayne was recommended to President Draper and she was hired in 1897 as the very first Dean of Women at the University of Illinois. She served on the university’s exclusive Council of Administration and was instrumental in developing female student organization to promote social responsibility among her students. She organized a special women’s issue of the Illini student newspaper in 1898, the only time within 26 years that female students contributed to the school paper, to encourage academic programs and social opportunities for women to become more independent. During this time, some female students were happy to follow the lead of their male counter parts, but other students and faculty members had a larger vision of independence for women and thought higher education should serve as a vehicle for this notion.

Around this time, the Watcheka League—which became known as the Women’s League in 1900 — emerged as an organization with “the aim of united action on the part of the women students of the University.”[8] Jayne contributed to the name of the organization, choosing the name from a legend of the Indian tribe of the Illini and symbolic of “the spirit and pride that [she] was attempting to create among the Illinae.”[9] However this was not the first organization instituted to benefit female students. In 1884, the Young Women’s Christian Association (Y.W.C.A.)—the oldest continually operating student YWCA in the country today—established itself on campus to support women.[10]

During Jayne’s time as Dean, the first basketball team at Illinois formed in 1897 and its composition was all women, surprisingly enough, because basketball was viewed as a feminine sport at the turn of the century. The team’s first inter-collegiate competition was against the women of Wesleyan and the Illinae were triumphant in victory.[11]

Other women’s organizations arose under Jayne’s regime as a result of her efforts to unite the female student body. The first national sororities on campus, Pi Beta Phi and Kappa Alpha Theta, were organized in 1895, although involvement in these groups was not encouraged by the Dean because they lacked the independent mindset she was attempting to impart on female students.[12]

With the advent of more female students towards the end of the nineteenth century came desires for designated buildings and spaces for these students. The Board of Trustees approved a Woman’s Hall in 1879, but they were unable to finance it. A request for a gymnasium for women students was denied in 1889 because the Board decided that it was inadvisable for women to take calisthenics. Eventually, the funding for a Woman’s Hall came through in 1902, thanks to the efforts of Lucy Flower and the wife of the state senator Henry Dunlap. Flower “wrote to all members of the Association of Alumnae requesting them to use their influence with their Representatives and Senators to pass a bill for an appropriation to build a Woman’s Building.”[13] The building itself was not erected until after Dean Jayne left the university in 1904 and Edmund J. James became president of the university.

Next to Dean Jayne, two notable faculty members from the early years are Katherine Sharp and Isabel Bevier. Katherine Sharp was the head mistress of the Library Science school after it was transferred to Illinois in 1897 from the Armor Institute (now Illinois Institute of Technology). She was selected by Melvil Dewey, creator of the famed Dewey Decimal System, as the best librarian in the country to start and lead a library school at Illinois. She developed the curriculum for educating library patrons and foundation for the success of the university’s library and library school. Isabel Bevier was appointed professor of household science in 1900 and advanced the Department of Household Science in a way that “brought distinction to the University of Illinois and led the way for universities across the nation and abroad.”[14] All of these women revolutionized higher education at the university during a time when women were not exceptionally valued in academia.

References

[1] Mary Loise Filbey, “The Early History of the Deans of Women, 1897-1923,” 1969, pp. 16, Filbey Family Papers 1900-1913, 1920-1961, 1969, Record Series 41/20/38, Box 1, University of Illinois Archives.

[2] Ibid., pp. 3.

[3] University of Illinois Board of Trustees, Seventh Report, (1874) pp. 92, 95.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Jacque Kahn and Kate Skozinski, “U of I’s Women in Sports.” LASNews Magazine, accessed March 31, 2016.

[6] Paula A Treichler, “Alma Mater’s Sorority: Women and the University of Illinois, 1890-1925,” in For Alma Mater: Theory and Practice in Feminist Scholarship, ed. Paula A. Treichler et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 14.

[7] University of Illinois Board of Trustees, Nineteenth Report, (1897), pp. 64.

[8] University of Illinois, Illini Women’s Number, March 11, 1898.

[9] Filbey, “Early History,” pp. 21.

[10] University of Illinois, “Annals” in The Alumni Record University of Illinois, ed. James Herbert Kelley (Chicago: The

Lakeside Press, 1913), pp. 39.

[11] University of Illinois, Illio (1898), pp. 113-114.

[12] Filbey, “Early History.”

[13] Alumni and Faculty Biographical (Alumni News Morgue) File, 1882-1995, Record Series 26/4/1, University of

Illinois Archives.

[14] Paula A. Treichler, “Isabel Bevier and Home Economics,” in No Boundaries: University of Illinois Vignettes, ed.

Lillian Hoddeson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004), pp. 32.

![]()

Student Activities

Student Life

With the downtowns of both Urbana and Champaign nearly a mile from campus, there weren’t many outlets for fun for early students, who had compulsory manual labor and military drill daily or weekly. Even the two original student organizations were geared to improving the minds and skills of students. When women were admitted in 1870, women’s organizations followed suit.

The first fraternity arrived in 1872, but Regent Gregory was so hostile, it had to go underground. Gregory’s successor, Selim Peabody, outright banned them, making them more popular and leading them to help force Peabody out. Sororities appeared in the mid-1880s, as did professional societies in chemistry and engineering, musical groups, and the YMCA and YWCA.

Students had very few outlets for fun in the very early days of the University. Downtown Champaign and Urbana were nearly a mile away and didn’t offer much in the way of entertainment besides billiard halls and saloons.[1] In any case, there was little time to indulge in extracurricular activities: from 7:15 in the morning until ten at night, students were usually in class, in chapel, or in the library.[2] Two hours of compulsory manual labor each weekday (students were at first paid eight cents per hour and later 12½ cents) and two or three hours of compulsory military drill each week added a little variety to the daily routine.[3] “Especial emphasis was placed on the dignity of labor,” an early student recalled, “and play was hardly worthy of consideration.”[4] The school’s motto was, after all, “Learning and Labor.”

Even the University’s earliest student organizations had a serious intent. Formed only five days after the University’s opening on March 2, 1868, the Adelphic and Philomathean literary societies sought the social improvement of its members. (Not coincidentally, the Philomathean motto was “Come Up Higher;” there may have been a double meaning here since the Philomathean—and Adelphic—club rooms were located on the top floor of University Hall.) These groups held concerts and literary readings, sponsored orations and debates, and, in general, helped students develop their powers of expression.[5] “Men who were afraid to try to make a public statement at the time they joined a literary society soon found they could be real speakers,” alumnus Charles Kiler maintained.[6]

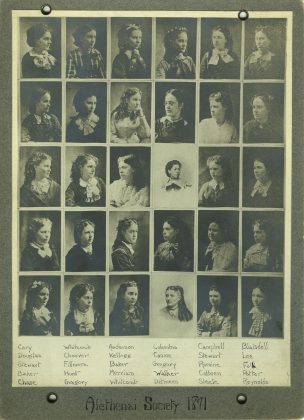

Shortly after being admitted in the fall of 1870, women students organized their own literary society, the Alethenai—Greek for “the truthful ones.” Members of the Alethenai hoped “to better themselves in composition, elocution, debating powers, and to enlarge their fund of general intelligence.”[7] In 1875 the Alethenai women challenged a local lawyer to a spelling bee. Twelve society women faced the lawyer and eleven fellow members of the bar in an event that was refereed by Regent John Milton Gregory. “It was quite exciting, for both sides went down at the same rate,” a witness reported. “At last two lawyers . . . and one Alethenai (Miss Adams) remained. It seemed as though neither would miss. At last the challenged lawyer missed and soon after Miss Adams failed on ‘palatable’.” The paid event attracted a large crowd and put a considerable sum into the Alethenai treasury.

The Illini student newspaper devoted five full paragraphs to the spelling bee and called it the “most exciting entertainment during the past month”–a statement that speaks volumes.[8] The Illini had come into existence only the previous year, having replaced the Student–a serious-minded, rather dull publication that ran from November 1871 until December 1873. Unlike the Student, which operated as a literary journal, the new monthly Illini aimed to “reflect the every day life of the school.”[9] Over the years the newspaper steadily increased its frequency of publication: in 1880, it began appearing every two weeks, in 1894 weekly, in 1899 tri-weekly, and finally in 1902 daily. The editorship in 1899-1900 of William Walter Smith, the University’s first African American graduate, marked a milestone in the history of the Illini. According to historian Winton Solberg, Smith “broke new ground with editorials that expressed opinions.”[10]

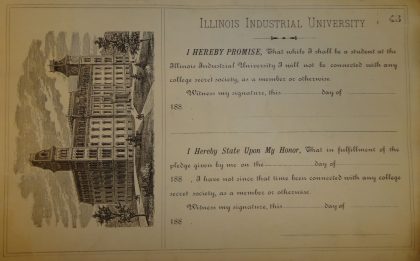

During these early years, the Illini remained largely silent on the controversial question of fraternities. A chapter of the Delta Tau Delta fraternity formed on campus as early as 1872, but was forced to go underground four years later because of John Milton Gregory’s hostility: The regent considered the secret societies to be undemocratic and unethical. Gregory did not go so far as to ban fraternities, but he did persuade the Board of Trustees to express its condemnation of them.[11]

Selim Peabody, Gregory’s successor, took a harder line against fraternities. Beginning in 1882, students were required to pledge that they would not join a fraternity. According to a woman student, the institution of the “iron-clad” anti-fraternity pledge came as “a mighty blow to the boys; I shall never forget the groan that followed this announcement at chapel by Dr. Peabody.”[12] The student continued: “evidently these college fathers did not know all about boys yet. It is said that the fraternities flourished even better after that, like the early Christians, whose persecutions only added to their numbers.” Indeed, the recently organized Sigma Chi chapter prospered for many years after the ban’s implementation, continuing its existence by means of a sham organization known as the Ten Tautological Tautogs.[13]

Fraternity men played a major role in forcing Peabody’s resignation in 1891. Thomas J. Burrill, Peabody’s replacement, was no fan of fraternities, but he “tolerated” them.[14] In September 1891 the Board of Trustees lifted the ban on Greek societies. Before long, Sigma Chi and Kappa Sigma had established chapters on campus: many more fraternities would follow suit, often setting up headquarters in rented spaces above downtown Champaign stores. In 1895 the first sororities appeared at the U of I–Pi Beta Phi and Kappa Alpha Theta. By the end of the Draper administration—in 1904—there were thirteen national fraternities on campus and five sororities; most of these Greek organizations then occupied frame houses on Green Street.[15]

Not just the Greeks were organizing during these years. Chemists and engineers and architects formed professional societies. In the mid-1880s, the Civil Engineering Club began publishing “a collection of technical essays comparable in many ways to the best articles in professional journals”; this publication, christened The Technograph in 1891, is still being issued today.[16] Another long-running campus institution—Star Course 1 | 2 | 3—emerged during this period, beginning life as a lecture course sponsored by the Adelphic and Philomathean literary societies.[17] The University Military Band, the University Orchestra, the Glee and Mandolin Club, the Ladies Glee Club, and the Oratorio Society all catered to “the muse of music.”[18] For the religiously inclined, there were the YMCA and the YWCA. In the early 1900s, over forty percent of the women students belonged to the YWCA and over thirty percent of the men to the YMCA.[19] First published in 1883, the YMCA-YWCA handbook introduced several generations of incoming freshmen to the University’s customs, traditions, rules, and regulations.[20]

References

[1] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois, 1867-1894: An Intellectual and Cultural History (Urbana: University of

Illinois Press, 1968), 169.

[2] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter

2, 28, University of Illinois Archives.

[3] Solberg, 110.

[4] Charles Jeffers Letter, 1937 July 23, Carl Stephens Papers (26/1/20), B: 8, F: Athletics, University of Illinois Archives.

[5] Solberg, 192-93.

[6] Charles Kiler, On the Banks of the Boneyard (Urbana: Illini Union Bookstore, 1942), 7.

[7] Stephens, Chapter 2, 28.

[8] The Illini, 1 April 1875.

[9] Solberg, 201-3.

[10] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois, 1894-1904: The Shaping of the University (Urbana: University of Illinois

Press, 2000), 275-77.

[11] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1867-1894, 201.

[12] Robert Jacobs, “The Fraternity System at the University of Illinois,” Greek Affairs Subject File (41/2/48), B: 55, F:

Jacobs, 58, University of Illinois Archives. | Link

[13] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1867-1894, 295.

[14] Kiler, 55.

[15] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 341-47

[16] Stephens, Chapter 3, 7.

[17] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 311.

[18] Ibid., 327-37.

[19] Ibid., 281.

[20] Stephens, Chapter 3, 7.

Explore Student Experiences

Further Resources

Student Regulations

Student discipline at first was severe—no smoking, no drinking, no noise in the hallways. In 1870, however, Regent Gregory established what may be the first student government in the country. Mimicking the federal structure of the U.S. Government, the elected body imposed fines for infractions of student code, including whistling, dancing, gambling, etc., until this experiment ended in 1883.

Regent Peabody imposed his own demerit system, which was so detested that in 1890, he was doused by students with a fire hose as he attempted to break up a dance. In 1891, a cadet rebellion helped force his resignation. Peabody’s successor liberalized many of these unpopular, puritanical policies.

During the first two years of the University’s existence, the faculty had the unenviable task of regulating student conduct. The Protestant faculty, the heavily Baptist Board of Trustees, and the Baptist regent set the school’s moral tone, giving it a distinctly “neo-puritanical” flavor. “Smoking was considered an evil and drinking an abomination,” Winton Solberg wrote.[1] In keeping with such an outlook, the faculty prohibited students from using alcohol and from visiting saloons, billiard parlors, and gambling halls. Students weren’t even allowed to make “unnecessary noise in the halls.”[2]

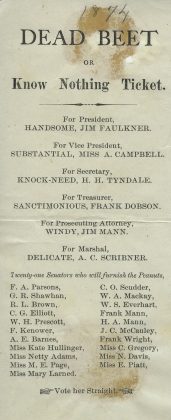

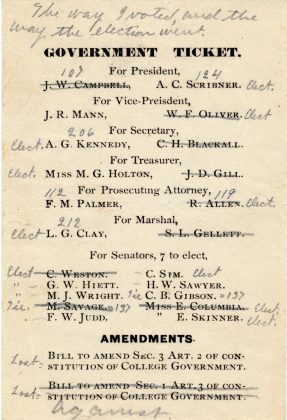

Regent John Milton Gregory did the unimaginable in the fall of 1870 when he ostensibly handed over control of student discipline to the students themselves. Gregory established a student government—possibly the first example of its kind in the United States. “You are young Americans,” Gregory declared to the students in October 1870, “you expect to govern yourselves and will be governors of the country by-and-by; why not begin now?”[3] Mimicking the structure of the federal government, the College Government initially had a General Assembly, a five-person Council with judicial powers, and an executive body made up of a President, Adjutant, and Hall Sergeants.[4] Parties with names like Government, Reform, Illini, Enforcement, and Dress Reform (pro-women’s rights) vied for the student vote.[5] James Robert Mann, a member of the Government party in the mid-1870s, went on to become the Minority Leader of the U. S. House from 1911 until 1919.

The Government set up a system of fines to punish misbehavior: misdemeanors of the first degree were subject to a fine of between $5 and $20; the second degree, $1 and $5; and the third degree, $1 or less. Students who swept their Dormitory rooms or set their “slop-pails” in the halls between 7 in the morning and 5 in the evening and those who disturbed the peace of University Hall or the Dormitory by “whistling, singing, dancing, or making any unnecessary noise during the time of study and quietness” were guilty of misdemeanors of the third degree. Students possessing “any vinous, fermented, spiritous, malt, mixed or otherwise intoxicating liquors” and those visiting “any drinking shop, or saloon, billiard hall, ball alley, or gambling house of any kind” were guilty of misdemeanors of the second degree.[6] The faculty members, however, still had disciplinary powers and exercised them in certain cases: in 1880, for example, they expelled a sophomore “for taking a woman of ill repute to the dormitory” and ordered him to immediately leave town.[7]

The College Government worked well for a time, but cracks soon began to develop. Early in 1872, the Government’s Council fined fifteen students who engaged in choir practice during study hours. Since a professor had approved the rehearsal, Regent Gregory told the choir members to ignore the Government. Student legislators objected to Gregory’s arbitrary action, and the Government’s position was ultimately sustained.[8] The Government, though, started to lose favor as its powers were expanded and as it increasingly became the plaything of rival student factions. (At an early date the Delta Tau Delta fraternity was rumored to have seized control of the Government.)[9] In 1883 the students voted to end Gregory’s “noble experiment,” and the faculty once again took full control of student discipline.[10]

Regent Selim Peabody did not mourn the demise of the College Government, and he soon established a demerit system as a replacement. Under this system, an individual teacher could give a student up to ten demerits for “any infraction of good order”: a total of 200 demerits resulted in the student’s expulsion. Students resented the demerit system, but peace reigned for a time after its imposition.[11]

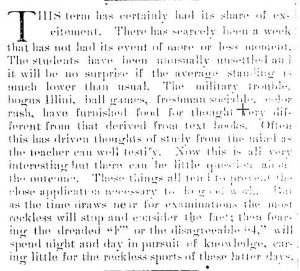

In 1887 the metaphorical dam broke, and “a new era of disorder,” in Solberg’s words, rocked the University.[12] Record numbers of students began to excuse themselves from chapel and military drill: the demerits piled up. In 1886-7 only two students had been given demerits, but in the following year 48 students received a total of 1260 demerits.[13] Even the regent himself became a target of student mischief. In 1890, when Peabody attempted to break up a forbidden dance held at the Drill Hall (now Kenney Gym Annex), he was greeted by students wielding a fire hose: the hose was turned on and Peabody was washed out of the building![14] Peabody’s misery came to a merciful end in 1891 when a cadet rebellion and a conspiracy hatched by a group of students and alumni helped force his resignation.[15] During the year of the rebellion, two hundred students had been awarded a staggering 6315 demerits.[16]

Peabody’s resignation and his replacement by Professor of Botany Thomas J. Burrill as acting regent marked a watershed moment in the history of student life at the University of Illinois. Under Burrill, Peabody’s hated demerit scheme was eliminated, the fraternity ban was lifted, chapel attendance was made voluntary, the requirements for military drill were reduced, an elective system of study was introduced, and athletics were encouraged.[17] One alumnus later claimed that the Burrill administration provided “the real start toward making our alma mater a great University.”[18]

Burrill also gave the faculty a role in the administration of the University when he created an executive committee of deans. That role did not last long. Under Andrew Draper, Burrill’s successor, the faculty lost most of their administrative powers, except those relating to educational policy and curricula. Draper assumed control of most University functions and set up the Council of Administration to serve as “the extended arm of the president.” Answerable only to the Board of Trustees, the Council was given exclusive control over student discipline.[19]

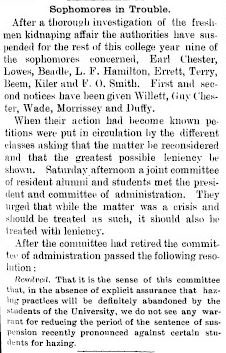

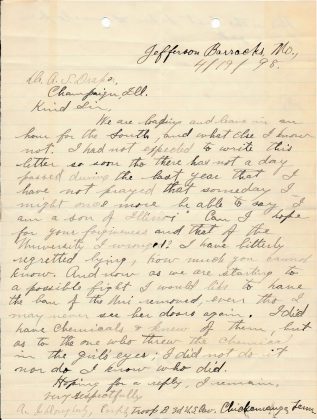

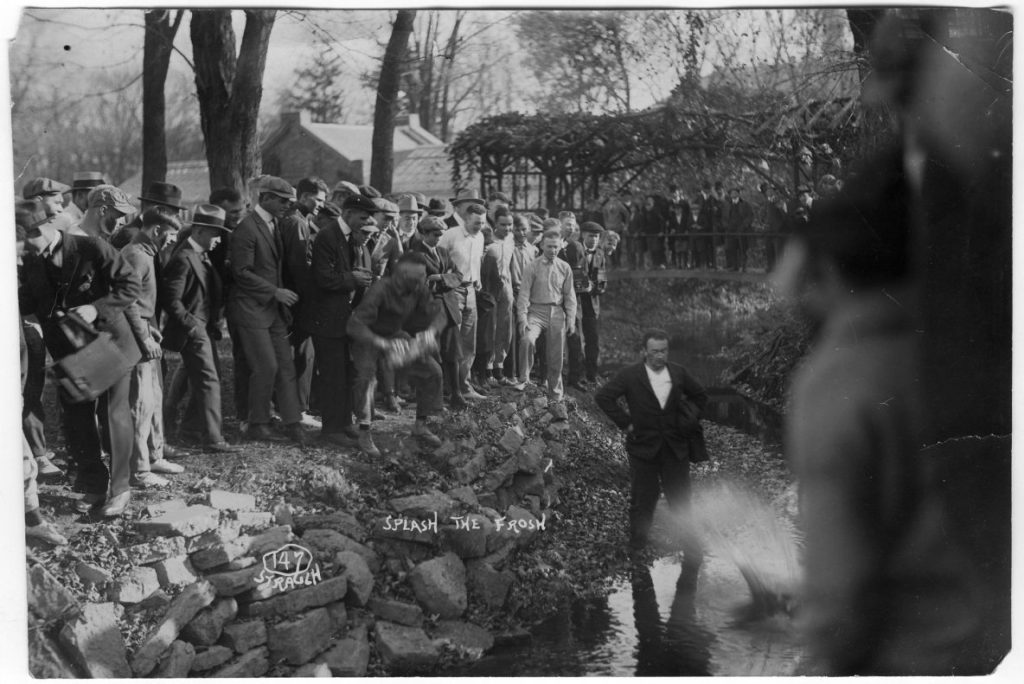

Disciplinary cases involving “boisterous” students kept the Council very busy during its early years. In February 1895 the Council suspended nine sophomores who kidnapped three freshmen, including the class president. The so-called “Naughty Nine” were re-instated as students after the freshman and sophomore classes renounced hazing. Two years later, sophomores, once again the culprits, broke up the freshman social using “eye water”: freshman Estella May Radenbaugh was blinded for two days after she got the chemical in her eyes. The Council expelled eight students for this action—the last six to face expulsion were dubbed the “Sinful Six.”[20] Andrew Jackson Dougherty, Jr., the first student to be expelled, later wrote to Draper confessing his guilt and begging for the forgiveness “of the University I wronged.”[21] The Council was faced with a new form of hazing in 1901 when boneyard dunking made its debut. Fueled by class rivalries, hazing grew progressively worse during the Draper years. Thomas Arkle Clark, Draper’s newly appointed Dean of Undergraduates, would spend his career combating such “deviltry.”[22]

References

[1] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois, 1867-1894: An Intellectual and Cultural History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1968), 180.

[2] Ibid., 184.

[3] Robert Jacobs, “The Fraternity System at the University of Illinois,” Greek Affairs Subject File (41/2/48), Box: 55, F: Jacobs, 41, University of Illinois Archives.

[4] Solberg, 185.

[5] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter

2, 33, University of Illinois Archives.

[6] “Constitution and Laws of College Government,” ca. 1875, Allen Family Papers (41/20/21), B: 2, F: I.I.U. Student Goverment Tickets, University of Illinois Archives.

[7] Solberg, 277-78.

[8] Ibid., 186.

[9] Stephens, Chapter 2, 33.

[10] Solberg, 280-83.

[11] Ibid., 289-90.

[12] Ibid., 317.

[13] Joseph DeMartini, “Student Protest during Two Periods in the History of the University of Illinois: 1867-1894 and 1929-1942” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Illinois, 1974), 162.

[14] Charles Albert Kiler, On the Banks of the Boneyard (Urbana: Illini Union Bookstore, 1942), 44.

[15] Solberg, 318-25.

[16] DeMartini, 162.

[17] Solberg, 343-44, 373-81.

[18] Kiler, 52.

[19] Stephens, Chapter 4, 18-20.

[20] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904: The Shaping of the University (Urbana: University of Illinois

Press, 2000), 297-300.

[21] Andrew Jackson Dougherty to Andrew Draper, 19 April 1898, Andrew Draper General Correspondence File (2/4/1), B:3, F. Dougherty, University of Illinois Archives.

[22] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 300-4.

Further Resources

![]()

Traditions & Sports

Students yearned for a school culture. Class rivalries filled that niche, resulting in classes adopting their own colors, yells, and symbols, and by 1872, class memorial gifts. By 1879, the rivalries became physical, often leading to injuries and, in one case, George Huff hanging from a chandelier. President Draper reined this in by promoting all-school spirit. By 1894, students had chosen all-school colors, songs, and yells.

Intramural and intercollegiate baseball and football were the big sports. By 1892, there was a director of athletics and a professional coach. In 1883, students formed the Athletic Association, leading to development of Illinois Field in 1896, the same year the University helped found the Big Ten.

Almost from the beginning, Illinois students attempted to create a culture of their own. No innovators, they naturally adopted the customs and traditions of the long-established Eastern colleges. Their literary societies, for example, were modeled on the literary societies of the East. Already in 1879, a writer for the Illini newspaper noticed the emergence of a definite student culture. “Although we are not a dozen years old,” the Illini editor wrote, “there are customs originating and habits being formed among us which will leave an indelible imprint upon the history of our University.”[1]

Like their peers in the Eastern colleges, Illinois students developed a strong attachment to their particular classes. “For four years a whole class marched in lock step through the same course of studies,” Winton Solberg wrote. “Members formed close personal bonds and developed intense loyalty to their class.”[2] Students identified more with their classes than with the University itself. Individual classes soon adopted their own colors, yells, and status symbols such as class canes. As early as 1877, the seniors chose plug hats as their symbol while the juniors showed their class rank by attending a party decked out in academic caps and gowns.[3]

Class memorials were another product of this so-called “class system.” Illinois seniors inaugurated an annual tradition in 1872 when they presented a stone tablet as a class memorial. Two years later, the members of the graduating class attempted to perpetuate their memory by planting a sycamore tree. The class memorials became more elaborate over the years: subsequent classes would bequeath to the University such gifts as the University Hall tower clock (1878), the Senior Bench (1900), the boulder drinking fountain (1902), a sun dial (1903), the bench and light (1912), and the Lincoln Hall gateway (1913).[4]

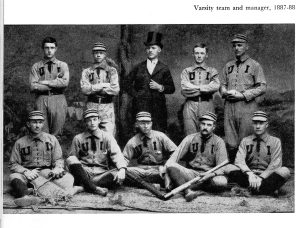

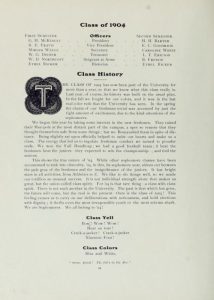

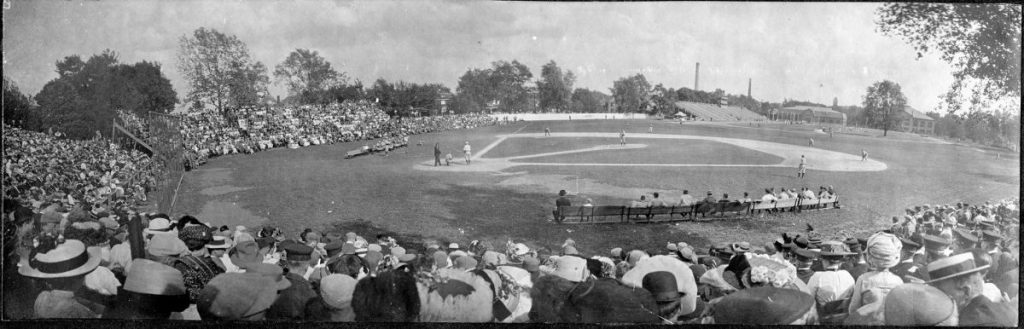

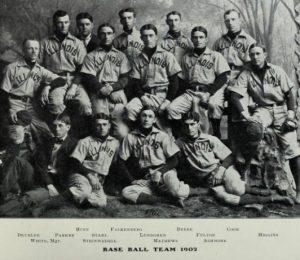

On May 8, 1872, a student team defeated Champaign’s Eagle Baseball Club by a score of 2-1 in what was the first athletic match held at the University. The University Baseball Association was formed in 1878, and the following year, Illinois entered the realm of intercollegiate athletics when, on October 2, 1879, its baseball nine defeated an Illinois College team, 12-5.[12] In those days, baseball took a back-seat to oratory, and intercollegiate baseball games were played at the annual Intercollegiate Oratorical Contests. But things had changed by 1887: that year the “oratorical” contest devoted three days to baseball and only one evening to oratory.[13] Illinois became a powerhouse in intercollegiate baseball under the leadership of George Huff. Members of the conference-winning 1902 team were hailed as “the champions of the United States” when, on an Eastern tour, they defeated Princeton, Army, Yale, and Pennsylvania, losing only to Harvard.[14] That famous team featured such future stars as Carl Lundgren, a Chicago Cubs pitcher for seven years, and Garland “Jake” Stahl, manager and first baseman of the World Series-winning 1912 Boston Americans.[15] On May 9, 1903, Stahl slugged ten home-runs in a game against Michigan.[16]

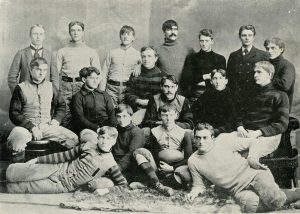

Football eventually overtook baseball as the preeminent college sport. The first football game on campus apparently occurred in about 1876, though Henry Dunlap, who was graduated the previous year, recalled students kicking a football–“a big, awkward, rounded thing”–“up and down the south end of the campus.”[17] Writing in the fall of 1878, the Illini claimed that “foot ball had entirely superseded base ball and all other kinds of amusement this season.” The Illini continued: “On every possible occasion the ball can be seen flying about, and boys with limping gaits, bandaged shins and skinned noses are no longer objects of sympathy, but rather he who has the most bumps and bruises, and can run the fastest and kick the hardest . . . is the hero.”[18]

The popularity of football grew slowly in the 1880s. In the spring of 1883 the student newspaper reported that the game had been “resurrected” after a period of dormancy and “the boys are once more furiously engaged in kicking each other.”[19] In the fall of 1888 two teams, one led by future Supervising Architect James White and the other by future Registrar William Pillsbury, battled on the gridiron in a game that resulted “in numerous bruised shins, and many stiffened joints.”[20] Two years later, freshman Scott Williams organized Illinois’ first “regular” football team. In its first intercollegiate match, held on October 2, 1890, the Illini eleven lost to Illinois Wesleyan by a score of 16-0. “The Wesleyans do nothing else but play football in the way of outdoor sports so they had the advantage over the U. of I. boys,” the Illini explained.[21] Later that season, an experienced Purdue team routed Illinois, 62-0. The Illini had “learned a great deal about foot-ball” from Purdue and closed out the year on a positive note, beating Illinois Wesleyan in a re-match, 12-6.[22]

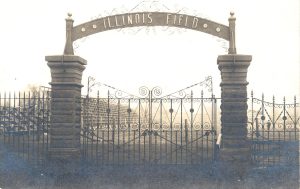

Despite this inauspicious beginning, football was here to stay. The forced departure of Regent Selim Peabody—a staunch opponent of collegiate athletics—paved the way for football and other Illinois sports. In June 1892 the University hired Edward K. Hall as the school’s first director of athletics and first full-time professional coach. In his first season as coach, Hall led the Illini eleven to a winning season—seven wins, three losses, and two ties. The Illinois football, baseball, and track teams now had a spacious new field for their endeavors thanks to the Athletic Association. Formed by students in 1883 and incorporated seven years later, the Athletic Association had taken the lead in promoting Illinois athletics. In 1891 the Association obtained $350 from the Board of Trustees for the development of the so-called Athletic Park on the north campus—the former site of “The Elephant.” Re-named Illinois Field in 1896, this park would long serve as a center of student activity–athletic and otherwise.[23] In 1896 Illinois co-founded the Intercollegiate Conference of Faculty Representatives, later known as the Big Ten.[24] The future of Illinois intercollegiate athletics was secure.

References

[1] The Illini, 1 December 1879.

[2] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904: The Shaping of the University (Urbana: University of Illinois

Press, 2000), 270.

[3] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter

2, 32, University of Illinois Archives.

[4] Daily Illini, 18 September 1932.

[5] Winton Solberg, The University of Illinois 1867-1894: An Intellectual and Cultural History (Urbana: University of

Illinois Press, 1968), 283-85.

[6] Charles Albert Kiler, On the Banks of the Boneyard (Urbana, Illini Union Bookstore, 1942), 30.

[7] Solberg, 311.

[8] Kiler, 46-47.

[9] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 270-71.

[10] Ibid., 271-74.

[11] Charles Jeffers Letter, 1937 July 23, Carl Stephens Papers (26/1/20), B: 8, F: Athletics, University of Illinois Archives.

[12] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1867-1894, 204-6.

[13] Joseph DeMartini, “Student Protest during Two Periods in the History of the University of Illinois: 1867-1894 and 1929-

1942” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Illinois, 1974), 169-70.

[14] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 375-76.

[15] Carl Stephens, “The University of Illinois–A History, 1867-1947,” Carl Stephens Manuscript History (26/1/21), Chapter

10, 8-9, University of Illinois Archives.

[16] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 376.

[17] Ibid., 357; Henry Dunlap, “Early Sports History,” Carl Stephens Papers (26/1/20), B: 8, F: Athletics, University of

Illinois Archives.

[18] The Illini, 1 December 1878. | Link

[19] Ibid., 7 April 1883.

[20] Ibid., 22 October 1888.

[21] Ibid., 11 October 1890.

[22] Ibid., 17 December 1891.

[23] Solberg, The University of Illinois 1894-1904, 357-58.

[24] Ibid., 362-63.

Further Resources