Everyday Newspaper Titles (Zzzzzz)

Do not waste your time counting sheep; if you’re having trouble settling in for your long winter’s nap, you might find newspaper titles as sedating as Seconal: the “Gazette,” the “Times,” the “Examiner,” the “Post,” the “Tribune,” the “Sun,” the “Star,” the “Journal,” the “News”… and then the hyphenated titles, formed by newspaper mergers: “News-Tribune,” “News-Gazette,” “Journal-Star,” “Sun-Times,” “Star-Tribune,”and on and on.

A handful of interesting exceptions do, however, cross my desk. I’m often puzzled by the “Sun-Star” and “Star-Sun” unions. Is it an unholy marriage of night with day, or a Rosicrucian signal: sun is star; star is sun; sun marries self, a terrible autogamy and its dread progeny? Imagine waking every morning, or returning home every evening, to that Yeatsian horror: “[W]hat rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?”(Oh, and, Merry Christmas, if you celebrate!)

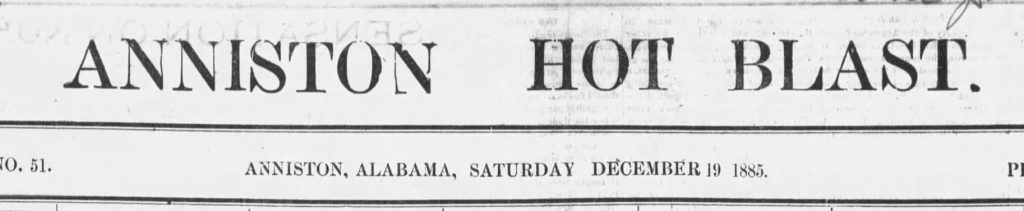

Of the exceptions, my favorite so far is the Anniston, Alabama Hot Blast.

The Hot Blast was published from 1883 through 1919, at which time its name became, alas, the Star. For thirty-five years, however, the residents of Anniston got their morning brain burn the honest way: hot off the press.

HPNL’s Winter Warmth Gift Guide

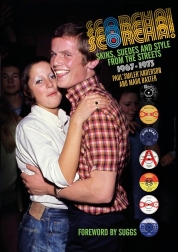

More heat coming your way from the best history book I read this semester, Scorcha!: Skins, Suedes, and Style from the Streets, 1967-1975. The title, I assume, refers to Errol Dunkley’s 1968 single, “The Scorcher,” a rocksteady masterpiece released in Britain on Trojan Records. Much of the book is about the influence of West Indian, especially Jamaican, immigrant communities on British youth culture, with this influence coming primarily through music—ska, reggae, and rocksteady. Here’s a sample from Dunkley’s recording:

Audio Player[Excerpt from “The Scorcher” by Errol Dunkley, ℗1968 Amalgamated Records, from The Scorcher / Do Right Tonight]

There are many books on British youth subcultures of this period, and, it must be said, most are better written and better designed than Scorcha!—see for example Ben Sherman: 50 Years of British Style Culture. After reading Scorcha!, however, I couldn’t help but feel these other books astonishingly superficial, the tidiness of the writing and the design perhaps reflecting an intellectual fastidiousness in the authors, a reluctance to stray far from Carnaby Street, where the young bought much of their clothing. Scorcha! certainly covers the shops, but it also gets into the discos, the streets, and the football terraces where all this clobber was actually worn. The book manages to capture that experience because it is part oral history and part scrapbook, which might account for the lack of polish on the prose: Scorcha! is without doubt a messy book, and sometimes difficult to follow. However, I came away with a better understanding of post-war British youth subcultures, which previously had largely been confined to the almost-textbook categorizations (Teds, mods, rockers, skins, and punks) that you get from movies like Quadrophenia and songs like “Suedehead.” This book would make an excellent gift for anyone interested in music, fashion, or just a bit of bovver.

Index, a History of The: A Bookish Adventure from Medieval Manuscripts to the Digital Age by Dennis Duncan. This was one of those books that a reader will sometimes describe as “a joy”; I certainly found it to be. Duncan is a gifted writer, and accomplishes the difficult task of writing a book that will appeal to the specialist and the generalist alike. I wanted the book to be longer, but really the book is just as long as it should be—those of us craving hundreds more pages on this subject are probably few in number and, alas, must yield to the majority. I also might have preferred more of the History and less of the Bookish Adventure: because the book is not long, every droll example occupies precious space: the mad index to Pale Fire is of course an index, and therefore part of its history; by that standard, however, Duchamp’s Fountain might command an entire chapter in the history of public health! Index, a History of The can also get a wee-bit Whiggish, a tendency I’ve noticed in other histories of information technologies, possibly a reaction against the Johnny-can’t-read crowd: these historians want to show that, no no no, the Internet represents continuity, not disruption, and that its impact on our reading is simply another development in a long series of changes inevitably greeted with panic by teachers and librarians and others tasked with shepherding society’s vulnerable youth along the path to wisdom. Duncan argues that the World Wide Web practically fulfills the index’s destiny! And, technically, he is correct, but he might here be guilty of mixing apples and oranges: the inverted files structuring online information retrieval systems fulfill the historical development of the concordance, not the subject index, the two technologies being related, but certainly not identical. I question how many users of the Internet even realize they are interacting with an index at all, and one of the book’s achievements is in making us see that we are. Even so, few readers will spend more than a moment contemplating the invisible index behind Google’s invitingly serene search box, especially since we are never permitted to view Google’s index, and anyway isn’t its invisibility part of its attraction: how many people would choose to heft a concordance onto their desks if they didn’t have to? These objections of mine are all, however, silly little quibbles, and should be taken more as evidence of how much I enjoyed the book, how engaging I found it, than actual flaws. Duncan wears his learning lightly, and makes a very companionable guide, a stark contrast to others working on the history of information technologies.

How Not to Kill Yourself: A Portrait of the Suicidal Mind by Clancy Martin. Self-help and do-it-yourself guides are two of the oldest book genres. The earliest known “How to” book that explicitly promised as much to its readers was published in 1595: How to Chuse, Ride, Traine, and Diet, both Hunting-Horses and Running Horses. Clancy Martin has taken the “How to” genre and come up with a title that, for sheer cleverness, almost any writer would kill for. It is, however, a strange title for so serious a book, you almost wonder if it didn’t come from the publisher, perhaps one of those precocious editorial assistants on-the-make. Whatever the title’s origin, it’s undoubtedly brilliant, but a complete mismatch for the book it’s tasked with headlining, since How Not to Kill Yourself is really a memoir, and a grave one at that. Martin teaches philosophy at the University of Missouri, which seems apt given that so much philosophy falls within the “how to” tradition: how to lead a good life, how to govern people, how to make effective arguments, and so forth. Clancy draws on this academic background to enrich his book with philosophy, literature, psychology, and religion.1 It’s his raw self-disclosure, however, that sears the reader. I felt awed by the courage it must have taken to write this book. He mercilessly dissects himself, exposing vulnerabilities that many would find difficult to share with a therapist: the demons of addiction, the multiple attempts at jumping headlong into death, the degradations of the psychiatric ward, the unbearable pain of feeling like a failed father and husband. Many readers will surely recognize themselves in the ferocity with which he anatomizes his life, the shame and self-hatred smothering his will to live like a father drowning the puppies he had told his children not to bring home. And most defeating of all, perhaps, is the unpredictable recrudescence of suicidal obsessions, which Martin effectively renders by mixing the steadiness of his philosophical perspective with the sudden, punishing intensity of the personal. How Not to Kill Yourself is a harrowing but ultimately hopeful book.

Notes

- For example: Socrates, Plato, Seneca, Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Fingarette, Paul-Louis Landsberg, William James, Heidegger, Hume; Yiyun Li, Nelly Arcan, Heinrich von Kleist, Édouard Levé, Emily Dickinson, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Goethe, Stefan Zweig; Freud, James Hillman, Edwin Schneidman; Buddha, Jesus, Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche.

![Cover of: The early years [sound recording] by Errol Dunkley. London : Rhino Records, 1995.](/hpnl/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2024/12/errol-dunkley.jpg)