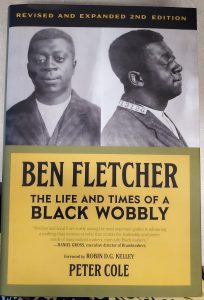

Simply put, Ben Fletcher was an African American dockworker from Philadelphia, a member of the Local 8 IWW (International Workers of the World) union in the early 1900s.

But Local 8, the IWW (known as “the Wobblies”), and Ben are not as simple as that. Fletcher became a man that “helped lead a pathbreaking union that likely was the most diverse and integrated organization (not simply union) despite the era’s rampant racism, antiunionism, and xenophobia” as stated on page one of Peter Cole’s Ben Fletcher: the Life and Times of a Black Wobbly.

Some of the existing unions Ben could have chosen to join (if they would allow a black man to join were):

-

Knights of Labor/K of L

-

International Longshoremen’s Association/ILA

-

American Federation of Labor/AFL

-

International Workers of the World/IWW/”Wobblies”

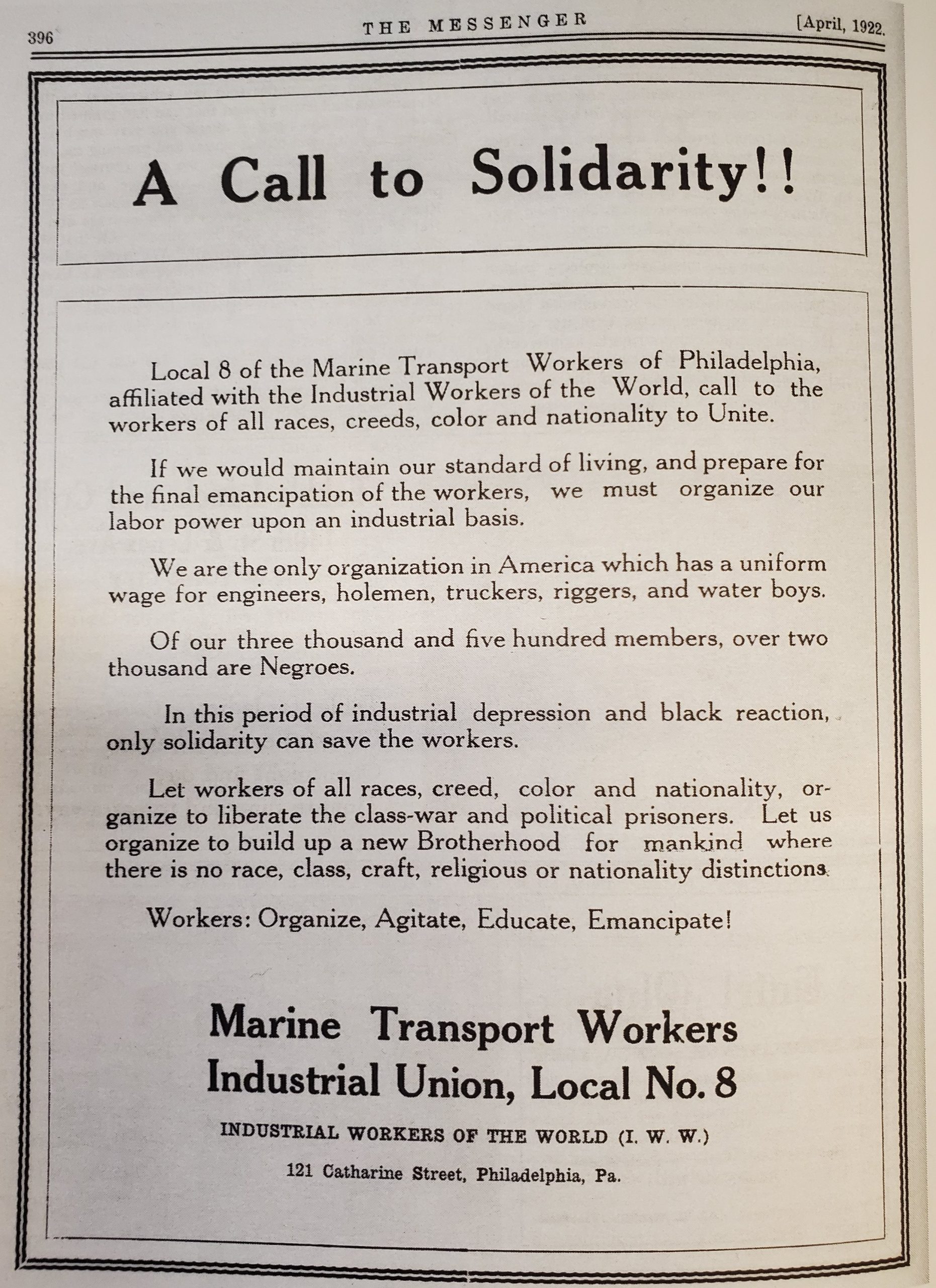

Ben chose to join the Socialist Party and the IWW early on in his working life. As an international union, it attempted (and is still attempting) to unite all workers, skilled or unskilled, of any race, gender, or creed against the owners of businesses across the world. They wanted to create O.B.U. (one big union). They were anti-capitalist and believed the workers, not the businessmen should reap the rewards of their work.

Ben was born (1890) and raised in Philadelphia, and that was his work base. He was a member in Local 8, but he would travel on behalf of the IWW to organize longshoremen and strikes along the Eastern seaboard, particularly Baltimore. He was reported to have been a very effective public speaker and natural leader. He seemed to prefer to work behind the scenes, being an invaluable link between the union and his local specifically, and as outreach to potential black longshoremen up and down the eastern coast in general.

Local 8 was unique at the time with its majority black membership and leadership that reflected its constituency on its board. Leadership rotated through the different groups (European immigrants (Jews, Poles, Irish, Slavs), European citizens (mainly Irish), and African American citizens) represented in the local.

The eastern seaboard ports were crucial during the U.S.’ participation in World War I. The government was not happy that these unions could negatively impact their war effort, and the IWW was the most radical union on the dock.

For most members of the IWW, they had no beef with the foreign workers (they actually wanted them all to be in the same “One Big Union”), now enemy soldiers, in other countries. It was the elites of the countries involved that would benefit from the war. Of course, the elites didn’t fight themselves; they sent their workers to fight on their behalf. The workers from the warring countries would simply be used, instead of in the factory or on the wharf by the elites, on the battlefield. This kept the workers from fighting their real enemy, that same ruling class.

The top level IWW leadership never officially spoke out against the war, but did allow locals to say what they wanted. The government started in with their Red Scare propaganda to turn the public against the IWW. Employers, not thrilled with having to deal with the IWW either, conspired with the government to oppress the IWW.

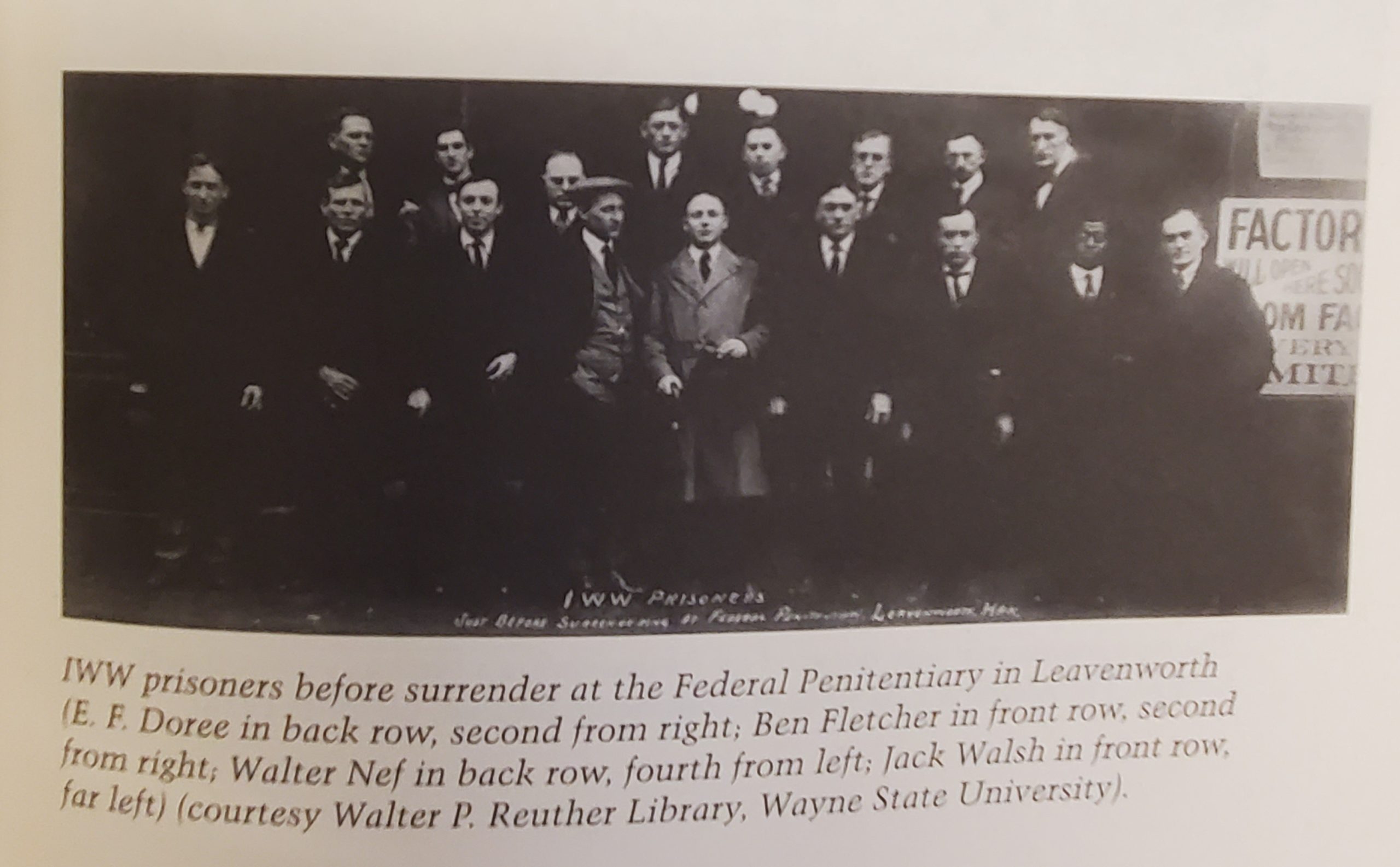

Fletcher was one of a number of Wobblies charged with crimes against the U.S. government. Specifically, Fletcher was charged with interfering with the Selective Service Act, violating the Espionage Act of 1917, conspiring to strike, violating the constitutional right of employers executing government contracts and mail fraud.

In 1918, he was sentenced to serve 20 years at Leavenworth (see the “War” section), but his sentence was commuted in 1922.

After he was released from prison, he continued to work with the now weakened union up to the time of his death in 1949.

By the way, the song Solidarity Forever was written for the IWW!

Bibliography

Cole, Peter. Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive-Era Philadelphia. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007.

Cole, Peter. Ben Fletcher: the Life and Times of a black Wobbly. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2021.

Dubofsky, Melvyn. We Shall be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World; edited by Joseph A. McCartin. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Spero, Sterling D. The Black Worker: a Study of the Negro and the Labor Movement. New York: Columbia University Press, 1931.

Thompson, Fred and Patrick Murfin. The I.W.W.: Its First Seventy Years 1905-1975. Chicago: Industrial Workers of the World, 1976.