One of the many benefits of working at a newspaper library is the ability to acquaint myself with the tremendous archive of historical newspapers available on both microfilm and online databases. These newspapers, ranging from local papers to underground zines to major titles like the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune, offer valuable insight into the cultural climate of their time period. For me, the most fascinating section of the paper is not always found under the front page headline. Often, it is situated far from the land of hard-hitting journalism, politics, and foreign affairs, somewhere closer to the crossword puzzle and the funnies. I speak, of course, of the advice column.

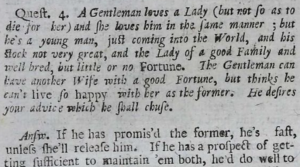

Advice columns have been around for almost as long as newspapers have been printed. The oldest of its kind can be found in the Athenian Mercury, a London-based periodical that ran in the 1690s. While the arcane language might be more challenging to decipher compared to the columns you will find in today’s newspapers, you may still find the subject matter of the queries familiar. Readers probe the columnist for guidance on issues related to religion, family, business, and other forms of interpersonal conflict. Consider one “queft” published by the Mercury, written by a gentleman pondering whether or not he should marry a woman he loves due to her lack of fortune. The response, in the vein of classic advice columns like Miss Manners, emphasizes the importance of following etiquette, reminding the letter-writer of his obligation to keep his promise to his betrothed as well as the inadvisability of marrying one he does not love, however rich.

To begin my research on advice columns, I decided to read up on Abby. Chances are, if you ever flipped open a newspaper over breakfast, you may have read the Dear Abby advice column. For Abby, AKA “Abigail Van Buren” AKA Pauline Phillips, giving advice to strangers was a family business. Phillips was the twin sister of Esther “Eppie” Lederer, better known as Ann Landers, the author of another popular advice column. The sisters’ relationship was reportedly rendered acrimonious due to competition between Lederer and Phillips’ respective columns. (If only there had been someone they could have turned to for advice!) However, both “Ask Ann Landers” and “Dear Abby” were staples of their time, infamous for their straightforward responses laced with wry humor and their willingness to broach some of the most taboo topics of the day, including drug use, pre-marital sex, and homosexuality.

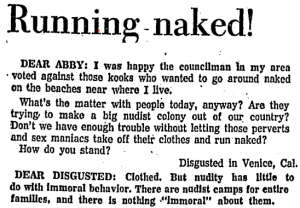

In one letter published by Dear Abby in a 1974 issue of the Chicago Tribune, the writer “Disgusted” laments the increasingly liberated attitudes towards sexuality and the body as represented by the presence of nude beaches in their community. Their declaration of “What’s the matter with people today, anyway?” reflects the conservative pushback to the free love movement and hippie sensibilities that had enchanted many members of America’s youth in the 70s. Van Buren, in her signature no-nonsense answering style, eschews any sentimental hand-wringing over public nudity. This brisk attitude, usually directed towards letters complaining about the apparent decay of family values, became increasingly noteworthy to me as I delved deeper into the Dear Abby archive. While she never goes so far as to rally for the complete upheaval of social mores, Abby is always quick to snuff out any hint of a moral panic.

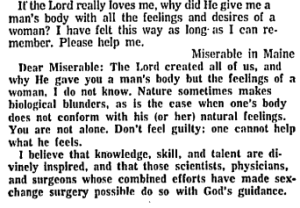

Even as Abby made her progressive stance known on issues like the gay rights movement, it would be reductive to label the Ask Abby column as overtly political or especially concerned with social activism. As many times as she advocated for increased social acceptance of marginalized groups, you will find remarks that reflect the deeply ingrained biases of the era she was writing in. Still, it is striking to read her columns written in the 80s during the height of the AIDS pandemic in which Abby calmly defers fear and paranoia from the general public over contact with gay people and minorities due to the spread of the disease. Her firm, fair, and mostly empathetic attitude towards those whose existence is often misunderstood or inherently politicized is exemplified in a 1977 column in which a letter-writer expresses emotional turmoil over their gender identity. The letter features this response from Abby: “The Lord created all of us, and why He gave you a man’s body but the feelings of a woman, I do not know. Nature sometimes makes biological blunders…You are not alone. Don’t feel guilty.”

Undoubtedly, some of her rhetoric would be considered outdated today. However, when viewed from the perspective of the 1970s, a time when LGBT issues were still not fully integrated into the mainstream, this response illuminates Van Buren’s profound disinterest in practicing any form of staunch morality which does not leave room open for an understanding of the unknown. Still, the explicit invocations of religion as a principal source of guidance foreground her column in a Scripture-based moral foundation that would likely resonate with the churchgoing readership, even as she occasionally breaks rank. (Van Buren/Phillips was Jewish; her pseudonym Abigail derives from the figure in the Book of Samuel from the Hebrew Bible.)

After reading my share of Dear Abby columns throughout the 70s, I found myself occasionally nodding in agreement and shaking my head in other cases. Sometimes I found her too stern to well-intentioned letter-writers, while at other times I felt she had made it obvious that certain blind spots existed in her moral code. In the end, I can’t say I saw Abby as any divine source of wisdom, and yet I feel this fallibility may be precisely the reason why so many strangers gravitated to her for guidance. As outspoken and witty as she was, Abby was also an ordinary woman, neither politician nor saint. She was living through the political tribulations and cultural upheavals of the late twentieth century alongside her readers. Her perspective was perhaps no more enlightened than your own or your neighbor’s, but the acuity and care she imbued in her every response served the much more valuable purpose of making people feel like their voices had been heard, the concerns they shared at the very least granted the validation of being printed in ink. You didn’t need to take her advice, and I’m sure many of the letter-writers did not. But what one would never be able to receive from long-dead sages like Plato and Socrates, perhaps not even from a prayer to their own deity, Abby delivered to their doorstep in every issue–namely, she reciprocated the conversation.

Recommended Resources:

Recommended Further Reading at HPNL and Other Libraries: