I like these first two lines from T.S. Eliot’s poem, “The Boston Evening Transcript.” I’ve clipped them (sort of) from the issue of Poetry magazine in which the poem first was published. Probably it’s a little strange that I should like them, because I don’t think he meant them to be lovely.

Actually, before I dig into those first two lines, it might be useful to stop and, for at least a moment, consider the poem in its entirety (an additional seven lines):

The readers of the Boston Evening Transcript

Sway in the wind like a field of ripe corn.When evening quickens faintly in the street,

Wakening the appetites of life in some

And to others bringing the Boston Evening Transcript,

I mount the steps and ring the bell, turning

Wearily, as one would turn to nod good-bye to Rochefoucauld,

If the street were time and he at the end of the street,

And I say, “Cousin Harriet, here is the Boston Evening Transcript.”

“The Boston Evening Transcript” shows us Eliot in his early, satirist phase. But what is he satirizing? Many readers of this poem surely interpret it as a satire of newspaper readers in general. I myself did at first. How many people today have ever heard of the Boston Evening Transcript? Eliot’s poem is probably now better known than the newspaper itself, which ceased publication almost a century ago. Never famous to begin with, and having printed its final issue in 1941, the Boston Evening Transcript here feels like a stand-in for all newspapers, and its readers for all newspaper readers, in part perhaps because consumers of mass media do tend to have a reputation for the kind of intellectual conformity that Eliot’s wheat field simile (technically a simile within a metaphor) implies.

A little knowledge, however, of American newspaper history in general, and of the Evening Transcript in particular, reveals the satire to be targeted, almost personal (with a strong resemblance to a poem E.E. Cummings wrote several years later, “The Cambridge ladies who lived in furnished souls”).

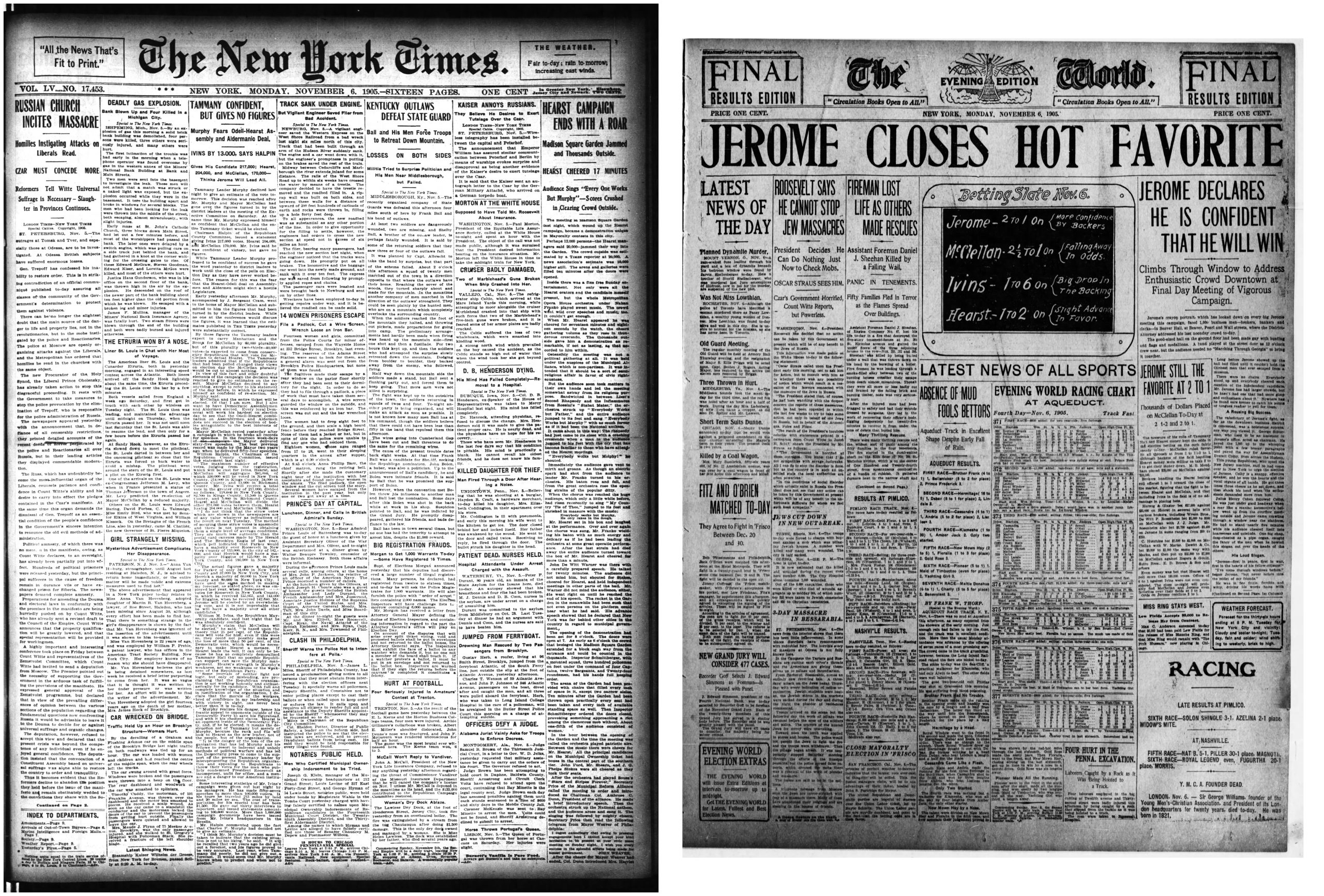

The first thing to know is that Eliot’s childhood in St. Louis through his time in Boston (roughly 1888-1914) coincided with a fierce resurgence of newspapers that combined aggressive editorial policy and sensational presentation of the news. Sensationalism had gone into abeyance following the Civil War, but regained popularity in the 1890s.1 Evening newspapers in particular became known for sensationalism, which often descended into pandering, especially as circulation wars broke out, in city after city, between the largest papers. In general, the morning papers of most cities aspired to a higher-toned respectability, while the evening papers went all-in for news, style, and page-design capable of driving circulation to dizzying heights. One of the most famous evening papers was the New York Evening World. Even a quick glance at its page design, beside that of a well-known morning daily, reveals much about its different approach to journalism:

Note how the Evening World makes liberal use of splashy banner headlines, a variety of display fonts (some of them quite unusual), and asymmetrical columns. The Times, in contrast, sticks to a rigid (I’m tempted to call it strait-laced), columnar layout, and uses display fonts both systematically and with restraint.

The second thing to know is that these evening papers were especially popular with female readers: “Women, with more leisure in the afternoons, liked the later papers; and since the department stores aimed their advertising at women readers, the evening papers fattened on the announcements of the stores.”2 Cousin Harriet, who makes her brief appearance at the poem’s end, might easily be just such a reader.

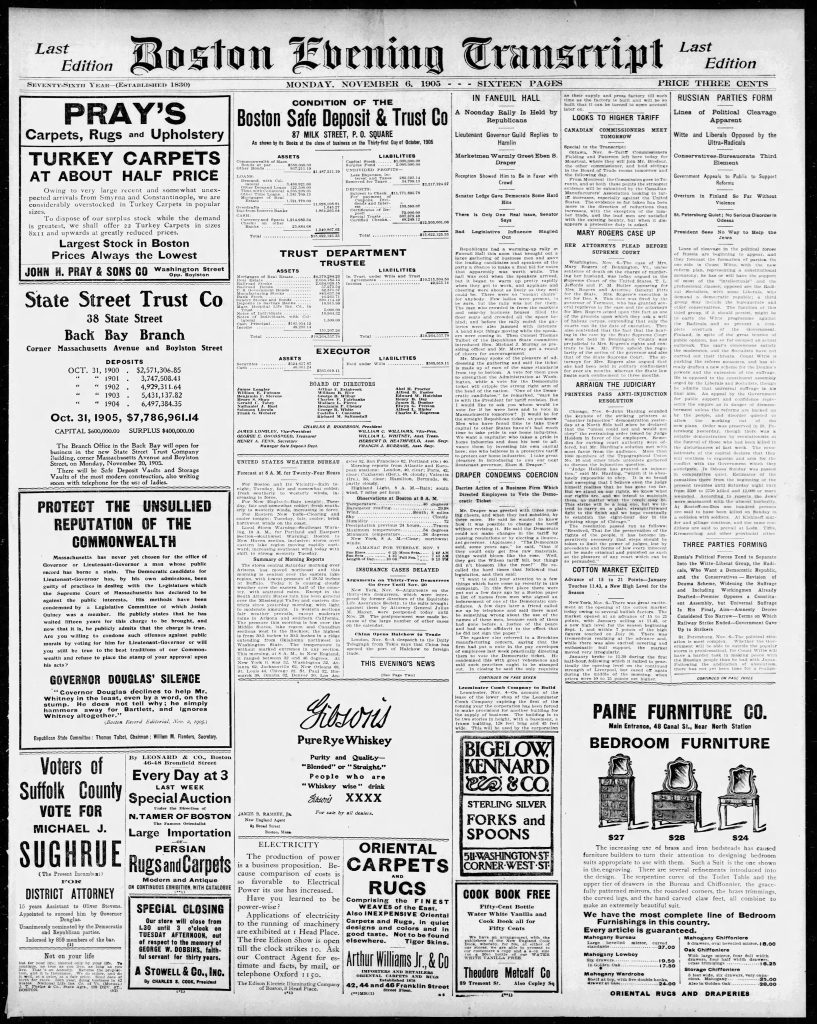

The third thing to know is that the Evening Transcript prided itself on most definitely not being like other evening papers: the Transcript was that rare thing, a highbrow daily published in the afternoon (so-called “evening papers” began issuing their earliest editions in the afternoon), and wore its low circulation numbers as a badge of honor, its handful of readers representing the city’s intellectual elite (note, for example, the way in which the poem contrasts those ruled by the viscera, line 4, with those ruled by the mind, line 5). Of Boston’s ten daily newspapers at this time, the Transcript consistently reported, by far, the lowest circulation of all. It had a reputation for being “stodgy” and “sedate,” making “few concessions to the moronic mentality of the enlarged reading public.” The Transcript instead regarded its readership as the enlightened few. In a fawning, quasi-official history of the paper (penned by one of its own journalists), Joseph Edgar Chamberlin wrote, “The Transcript might fairly claim that from the start it was the leading arbiter of literary questions in Boston.”3 Again, considering only the page design, the Transcript more closely resembles the New York Times than it does the Evening World:

The typographic variety you probably notice in this example is actually a case of tradition (and therefore archly conservative) rather than novelty: by 1905 few newspapers still featured advertisements on their front pages.

With this information in mind (about evening papers in general, and the Transcript in particular) the poem begins to feel more and more like a very specifically sexist satire of women who cherish pretensions to culture and taste, rather like the complacent, self-anointed highbrows Eliot satirized in a more famous poem, the women who “come and go / Talking of Michelangelo,” but who nevertheless fall back upon conventional opinion, with “eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,”4 which would explain why, as the speaker prepares to greet Cousin Harriet, he bids farewell to the apparition of Rochefoucauld, a man who made his reputation in part by puncturing hollow pieties and received opinion. Cousin Harriet passively receives her copy of the Evening Transcript from the hands of her nephew, and she’ll passively receive her opinions from the pages of the newspaper: what to like and what to dislike, what to approve and what to disapprove. The triumph of staid, received opinion.

That, in short, is the poem as a whole: a snobbish attack on a snobbish newspaper and its snobbish readers. What I really wanted to write about, however, were those wonderful opening lines, with which I began this post. Eliot was already living in England when he published the poem, but he had only been there a year or two. His usage of “corn” is surely either pastoral poetic diction or British affectation, because American corn doesn’t really sway in the wind, at least not in the manner I think he means here. He probably imagined something more like British corn (what Americans would call wheat):

Even if the paper’s readers did have the same, or similar, responses to its articles—like all those stems of wheat bending in response to the same wind—do those responses, those experiences of reading, cease to be personal? Or is newspaper reading more like a pavane between the newspaper and its readers? Also, I happen to like the image of all these readers responding together to the newspaper’s gentle sway. It evokes the gestalt of newspaper reading: not just the wholeness of the newspaper itself—gathering as it does dozens and dozens of discrete stories—but also the corporate body of newspaper readers, all reading the same paper at roughly the same time (evening, in this case) and roughly the same place (the city of Boston and its suburbs). The wind flows over the lithe corn, like the flow of time, and a newspaper is part of that flow, carrying its readers forward into the future, as on the crest of a wave, the news unfolding, figuratively and literally, day-by-day, on and on. Even researchers using a newspaper to plumb the past must surely feel this inexorable tug toward the future, every issue making us wonder, “but what will happen tomorrow?”

Notes

1.Willard Grosvenor Bleyer, Main Currents in the History of American Journalism (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1927), 322. Sensationalism included what became known as “muckraking” and “yellow journalism,” but was also a more general trend.

2. Frank Luther Mott, American Journalism: A History, 1690-1960, 3rd ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1962), 447.

3. Alfred McClung Lee, The Daily Newspaper in America: The Evolution of a Social Instrument (New York: Macmillan Co., 1937), 9, 597; Arthur M. Schlesinger, The Rise of the City, 1878-1898 (Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, 1999), 187; Joseph Edgar Chamberlin, The Boston Transcript: A History of Its First Hundred Years (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1930), 322.

4. T.S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” Poetry 6, no. 3 (June 1915): 130-35.