This blog post is part of a series exploring the important events and people in ALA’s history for the celebration of the 150th anniversary of ALA in 2026.

Wilson Bulletin editor, Stanley J. Kunitz, called it the “The Spectre at Richmond” – but the racial discrimination at the 1936 ALA Annual Conference was no ghostly apparition.[1] The conference was held in Richmond, Virginia, a city with Jim Crow era racial segregation laws. While the American Library Association itself had no segregation or discriminatory policies, up until 1936 they had not established any ruling against holding a conference in a segregated city where members would be subject to discrimination. Thus, “the Spectre” marched into the halls of the hotels and auditoriums, reminding all librarians present that there was still work to be done.

In December 1934, the Executive Board voted to hold the 1936 ALA Conference in Richmond. By August of the following year, they had signed contracts with the Richmond Chamber of Congress and the John Marshall Hotel, agreeing to the unequal treatment of Black librarians at the conference. The contracts provided that Black librarians “be admitted to all meetings except those in connection with meals,” stay in different hotels than white librarians, and have separate seating at meetings, in accordance with Virginia laws.[2] This would exclude Black librarians from casual, and fruitful, interactions with their white colleagues, as one editorial in The Library Journal aptly stated that “seeing old friends, talking with others doing the same type of work or entirely different work, coming into contact with new personalities, or exchanging ideas over a breakfast or luncheon table are an integral part of any Conference.”[3] One protester stated that these casual meetings, to which Black librarians were denied participation, provide “much of the inspiration of librarianship.”[4]

Awareness of the situation in Richmond began to spread in December 1935, when a circular letter was sent to officers of affiliated organizations, sections, and groups meeting at the Richmond Conference. The letter informed them of the segregation requirements at meetings. It also said that Black librarians could arrange to have separate meetings “devoted to problems especially their own” at the conference.[5] This letter was not forwarded to Black librarians or delegates. Instead, a separate letter was sent in February 1936 by Wallace Van Jackson, a Black librarian at Virginia Union University, outlining the segregation provisions that would be enforced at the conference.[6] Van Jackson wrote in The Library Journal about his discussion with the chairman of the local committee that led to him writing this letter, which was sent to about 200 librarians. He clarified in a second letter that he was against segregation and only planned to attend meetings where he would be treated the same as any other ALA member. He continued to write and protest the conditions, pushing for the ALA to create a policy to only hold conferences in cities where all members could participate equally.[7]

The Richmond Conference was attended by over 2,800 people from May 11-16, 1936.[8] According to Van Jackson, about 25 Black librarians attended the conference.[9] There were 8 attendees from the historically Black Hampton Institute Library and Library School.[10] This included Virginia Lacy Jones, a Black librarian who was able to pass for white and fully participate in the conference.

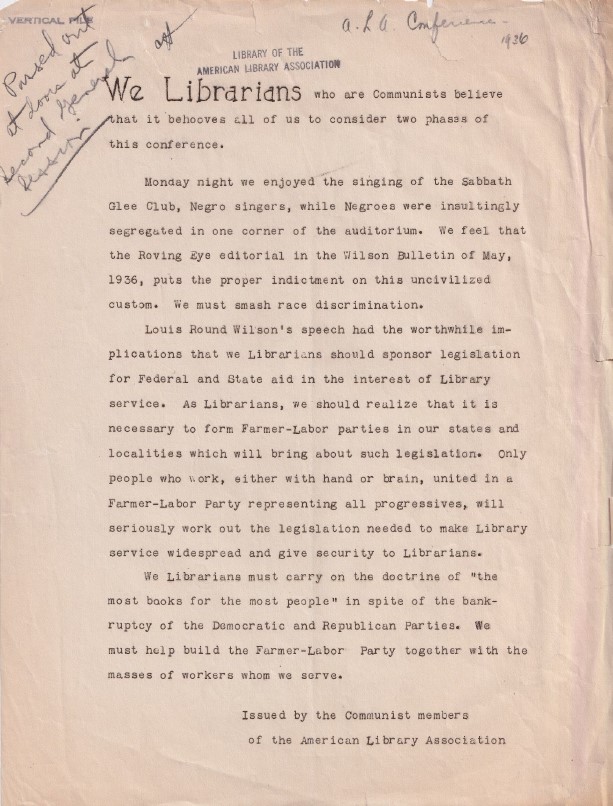

Despite the unequal treatment of Black librarians at the conference, there is little evidence of protest during the meetings.[11] All that remains in the historical record is a letter that was circulated at the second general session from the Communist members of the ALA. They pointed out the insulting way the conference was opened with a performance by the Sabbath Glee Club, a Black choir, while the Black librarians were in segregated seating in a corner of the auditorium.[12] While little comment was made on the subject during the general meetings, the Executive Board met on May 10, in response to protests received in the months prior, to discuss “the question of racial discrimination.” The Board unanimously affirmed the ALA’s acceptance of all members regardless of race or color and voted to create a Committee on Racial Discrimination to report in December.[13]

The published response to the Richmond Conference was overwhelmingly negative. It began with an article by the editor of the Wilson Bulletin criticizing the segregation practices of the conference and calling the librarians at the conference to action.[14] Librarians wrote letters to the editor in The Library Journal and the Wilson Bulletin for Librarians protesting the choice of a segregated city for the conference of an organization in which all members were supposed to be treated equally.[15] For months following the conference, librarians protested that “under no circumstances should the A.L.A. allow Negro discrimination to occur at any library conference.”[16]

The contracts for the 1937 Annual Conference, to be held in New York City, were ratified in October with a clause stipulating equal treatment for all members of the association at the conference.[17] When selecting the location of the 1938 conference in December 1936, the Executive Board was mindful of the discrimination issue, and unanimously voted on Kansas City. That same day, the Board read a proposed report from the Committee on Racial Discrimination. While supportive of protection against professional discrimination, the Board thought the report was “too specific to be carried out” and asked them to revise it “toward the adoption of general principles assuring professional non-discrimination.”[18] The revised report was approved the next day and published in the ALA Bulletin in January 1937. The policy is as follows: “In all rooms and halls assigned to the American Library Association hereafter for use in connection with its conference or otherwise under its control, all members shall be admitted upon terms of full equality.”[19]

It was briefly proposed by the Council in December 1939 to reconsider the 1936 resolution, but this was met with significant protest, including from a member of the original Committee on Racial Discrimination.[20] In May of 1940, the Council and the special committee that had been established, chaired by Ernestine Rose, notified ALA members that no change would be made to the 1936 resolution.[21] It wasn’t until 20 years after the Richmond Conference that a conference was held in the South again, in Miami Beach, Florida, in 1956.

—

[1] Stanley J. Kunitz, “The Spectre at Richmond,” The Roving Eye, Wilson Bulletin for Librarians 10, May 1936, 592-3.

[2] “Memorandum about Negro Delegates to Richmond Conference”, May 4, 1936, Transcripts of Proceedings, 1909-46, 1951-2002, Record Series 2/1/1, Box 1, Reel 3, v. 7, American Library Association Archives at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

[3] “Personal Contacts at Richmond,” editorial, Library Journal 61, May 1, 1936, 364.

[4] Edith N. Snow, letter to the editor, Library Journal 61, May 1, 1936, 341.

[5] Carl H. Milam to Officers of Affiliated Organizations, Sections and Other Groups Meeting at Richmond, December 2, 1935, Circular Letters, 1923-1954, Record Series 2/4/3, Box 11, v. 13, Part 4, American Library Association Archives at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

[6] Full text of this letter was printed in the Wilson Bulletin and Library Journal:

Kunitz, “The Spectre at Richmond.”

“Comments Wanted,” editorial, Library Journal 61, May 15, 1936, 387.

[7] Wallace Van Jackson, letter to the editor, Library Journal 61, June 15, 1936, 467-8.

Wallace Van Jackson, letter to the editor, Library Journal 61, August 1936, 563.

[8] “Attendance Summaries,” Bulletin of the American Library Association 30, no. 8 (1936), 842–43.

[9] Van Jackson, letter to the editor, June 15, 1936.

[10] “Attendance Summaries.”

[11] Casindania P. Eaton, letter to the editor, Library Journal 61, June 15, 1936, 468.

[12] Communist members of the American Library Association, circular letter, May 12, 1936, Annual Conference Programs, 1876-, Record Series 5/1/1, Box 6, Folder: Richmond, 1936, American Library Association Archives at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

[13] Executive Board Minutes, May 10, 1936, Record Series 2/1/1, Box 1, Reel 3, v. 7, American Library Association Archives at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

[14] Kunitz, “The Spectre at Richmond.”

[15] Numerous letters to the editor on this subject are in the May through October issues of The Library Journal, and articles also appear in the May and June issues of the Wilson Bulletin.

[16] LeRoy Charles Merritt, letter to the editor, Library Journal 61, June 15, 1936, 467.

[17] Executive Board Minutes, October 1, 1936, Record Series 2/1/1, Box 1, Reel 4, v. 8, American Library Association Archives at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

[18] Executive Board Minutes, December 28, 1936, Record Series 2/1/1, Box 1, Reel 4, v. 8, American Library Association Archives at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

[19] C. B. Roden, “Report of the Committee on Racial Discrimination,” Bulletin of the American Library Association 31, no. 1 (1937): 37–38, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25688988.

[20] “Midwinter Council Minutes,” ALA Bulletin 34, no. 2 (1940): 138–42, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25690387.

Mollie E. Dunlap, letter to the editor, ALA Bulletin 34, no 4, April 1940, 300.

[21] “A.L.A. NEWS.” ALA Bulletin 34, no. 6 (1940): 412–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25690477.