This blog post is part of a series exploring the important events and people in ALA’s history for the celebration of the 150th anniversary of ALA in 2026.

October 26, 2001, marked the beginning of a 15-year-long struggle for the privacy rights of library users as a result of the USA PATRIOT Act being signed into law by President Bush. The Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act, colloquially known as the Patriot Act, expanded surveillance and investigation capabilities of law enforcement to combat terrorism after the attack on September 11th.[1] Included in the bill was Section 215, which became known as the “library provision” as it allowed intelligence agencies to “obtain information about members of the public, including library records, based on a minimal submission to a secret court.”[2]

Prompted by the immediate possibility of government agents ordering libraries to turn over patron information, the ALA Washington Office created the “Guidelines for Librarians on the U.S.A. PATRIOT Act: What to do before, during and after a ‘knock at the door?’” which provided guidance on consulting legal counsel and reviewing policies.[3] Librarians largely opposed the Patriot Act as it “eliminate[d] the due process and probable cause protections guaranteed by the Constitution to library users.”[4] This meant the FBI and other government agents could demand patron information, such as records of books borrowed. To protect patron confidentiality, libraries adopted the common practice of only temporarily holding onto patron records. This angered government officials like former US Attorney General John Ashcroft, who claimed librarians had been persuaded to mistrust the government through “breathless reports and baseless hysteria.”[5] However, as former ALA president Maurice J. Freedman explained, librarians are trusted by their patrons and committed to confidentiality and privacy rights.[6] Section 215 of the Patriot Act, for many librarians, was an abuse of power in the name of national security.

The ALA additionally opposed the National Security Letter power given to law enforcement by the Patriot Act, which allowed “government agents to obtain sensitive information about innocent Americans without any court order.”[7] Government agents could impose a gag order upon recipients of these requests, such as librarians and booksellers, prohibiting them from informing patrons and colleagues about these investigations.[8]

One such investigation hit close to home for former ALA President Carol Brey-Casiano in early 2002. Working as Director of the El Paso Public Library, Brey-Casiano was approached by Texas Rangers who demanded that computer sign-up sheets be handed over as evidence for an investigation into a suspicious threat sent from a library computer.[9] She told the Rangers they would need a court order to access patron records. One of the Rangers attempted to invoke the Patriot Act’s authority, which Brey-Casiano refused due to the Rangers being state, not federal, law enforcement agents. When the court order was produced the following day, the sign-up sheets had already been shredded, which regularly happened every night. Brey-Casiano was subjected to an official investigation due to her actions and was ordered not to discuss the investigation by the mayor. She consulted with a lawyer and applied for assistance from the Merritt Humanitarian Fund to pay the fees associated with the case.[10] The Leroy C. Merritt Humanitarian Fund provides aid to librarians who are discriminated against or denied employment rights because of their defense of intellectual freedom.

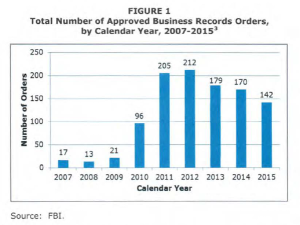

Eventually, after police interviewed her entire staff and intense isolation due to the gag order, the charges against Brey-Casiano for withholding information were dropped.[11] There is no knowing how many librarians were approached in similar ways over the years of the Patriot Act’s existence. There were multiple hundreds of Section 215 orders approved by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court from 2002-2015, and tens of thousands of NSLs issued by the FBI. Government reports do not reveal the number of these orders given to libraries.[12]

Section 215 did not expire until June 1, 2015, despite the continued efforts by the ALA and other library associations to speak out about the threat by government mass surveillance to constitutional rights, patron privacy, and freedom of access to information.[13] The section was revised slightly in 2006 but continued to be included in extensions of the Patriot Act in 2009 and 2011. It wasn’t until the sunsetting in 2015 and the passage of the USA Freedom Act, which the ALA saw as “the first meaningful reform of our surveillance laws in almost 15 years,” that librarians and library users could feel free of the dangers of Section 215.[14] While there is still more work to be done on ensuring patron privacy and intellectual freedom, the limitation of Section 215 and the National Security Letter powers of the federal government marked the end of ALA’s lengthy struggle against government mass surveillance of library records.

—

[1] “USA PATRIOT Act,” American Library Association, May 29, 2020, https://www.ala.org/advocacy/patriot-act.

[2] “Library Associations Statement On The USA PATRIOT Amendments Act of 2009,” American Library Association, Association of Research Libraries, October 29, 2009, https://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/advocacy/content/advleg/federallegislation/theusapatriotact/house-jud-1pgrpsaFINAL%2010%2029%2009.pdf.

[3] January 19, 2002, https://www.ala.org/sites/default/files/advocacy/content/advleg/federallegislation/theusapatriotact/patstep.pdf.

[4] Maurice J. Freedman, “Librarians fight to protect your privacy,” The Journal News, September 19, 2003, Maurice J. (Mitch) Freedman Papers, 1996-2005, Record Series 2/1/44, Box 15, Folder 9: “Librarians fight to protect your privacy,” The Journal News Op Ed 9/19/2003, American Library Association Archives at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

[5] John Ashcroft, “The Proven Tactics in the Fight against Crime,” prepared remarks for the National Restaurant Association, Washington, D.C., September 15, 2003, https://www.justice.gov/archive/ag/speeches/2003/091503nationalrestaurant.htm.

[6] Freedman, “Librarians fight to protect.”

[7] “Library Associations Statement.”

[8] Maryland Library Association Intellectual Freedom Panel 2017, Intellectual Freedom Manual (Maryland Library Association, 2017), The USA PATRIOT Act and Libraries, 17-19, https://www.mdlib.org/files/docs/divisions/ifap/patriotact.pdf.

[9] “Carol Brey-Casiano Tells a Patriot Act Story,” American Libraries, June 29, 2010, https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/blogs/the-scoop/carol-brey-casiano-tells-a-patriot-act-story/.

[10] For more information, consult LeRoy C. Merritt Humanitarian Fund Correspondence, 1970-2010, Record Series 6/5/5, Box 2, Folder: 2002, Carol Brey, American Library Association Archives at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

[11] “Carol Brey-Casiano Tells a Patriot Act Story.”

[12] U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General, A Review of the FBI’s Use of Section 215 Orders for Business Records in 2012 through 2014, September 29, 2016, https://oig.justice.gov/reports/review-fbis-use-section-215-orders-business-records-2012-through-2014.

“Surveillance Under the Patriot Act,” American Civil Liberties Union, accessed October 2, 2024, https://www.aclu.org/issues/national-security/privacy-and-surveillance/surveillance-under-patriot-act.

[13] “ALA cheers expiration of intrusive Patriot Act provision,” American Libraries, June 1, 2015, https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/blogs/the-scoop/ala-cheers-expiration-of-intrusive-patriot-act-provision/.

[14] American Library Association, “ALA calls passage of USA FREEDOM Act a ‘milestone,’” news release, June 2, 2015, https://www.ala.org/news/2015/06/ala-calls-passage-usa-freedom-act-milestone.