This blog post is part of a series exploring the important events and people in ALA’s history for the celebration of the 150th anniversary of ALA in 2026.

The ALA predicted the future 62 years ago in Seattle – the future of libraries, that is. They called their premonition “Library 21,” an exhibition at the 1962 World’s Fair. The “automated” library of the future would blend traditional library services with advancements in information technology. Partnered with companies including Remington Rand-UNIVAC, Xerox, RCA, IBM, and Encyclopaedia Britannica, Library 21 explored the importance of library services in daily life and how “electronics and information technology will have great impact on the methods we use for storing, retrieving, and communicating knowledge in the libraries of tomorrow.”[1]

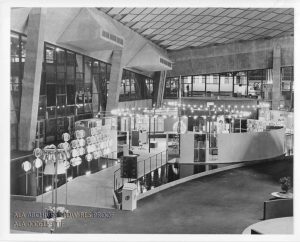

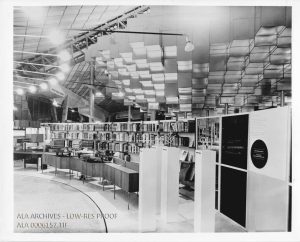

The 9,000 square foot exhibit space was the first exhibit on the ground floor of the Washington State Coliseum, which drew large crowds during the Fair’s run from April 21 through October 21, 1962.[2] An estimated 1.8 million people visited Library 21 – almost 20% of the total attendance of the Fair.[3] Designed by Vance Jonson of Los Angeles and constructed by the firm Daniel, Mann, Johnson and Mendenhall, the exhibit structure itself was quite impressive. The futuristic exhibit consisted of two large circles connected to form a figure eight, with stairs from the second circle leading to the colorful Children’s World below. The circles were lit from above and surrounded by reflecting pools. Visitors approached via a bridge into the first circle, which included the UNIVAC computer, the Ready Reference Center, and the adult reading area. The second circle contained the Xerox Theater, Learning Resources Center, and other electronic exhibits.

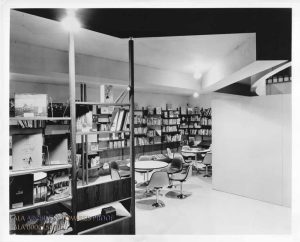

Library 21 was staffed by approximately 72 professional librarians from across the country, serving six-week terms and fulfilling different roles such as in reference or Children’s World. Before they started, each group of librarians completed a one-week training course in information retrieval and electronic media.[4][5] These librarians played a vital role in both the day-to-day running of the library and the overall success of the exhibit.

A major component of the exhibit was a UNIVAC computing system, which could allow patrons to “carry on ‘conversations’ with great minds of the past… [and] obtain personalized reading lists.”[6] The exhibit space also contained a video library, showcasing ‘on-demand’ global information; a micro image library; a Learning Resources Center highlighting educational media; and a Xerox photocopier, among other elements designed to depict the influence of technology on future library services. While some people were disappointed in the limited capabilities of the UNIVAC computer, most of the response to the overall exhibit was positive.[7][8] As one librarian who worked there explained, “it is more important to recognize that thousands enjoyed the exhibit and left with a better understanding of libraries, librarianship, and machines.”[9]

The exhibit also gave patrons an opportunity to explore the books on the shelves of a future library. The library was divided into sections: reference, children, and adults. The librarians at the reference desk were prepared to provide quick reference services.[10] The reference section contained over 700 volumes, which included materials on the pacific northwest (151 volumes) for local reference queries.[11] The adult collection included approximately 1,000 volumes. The children’s collection consisted of more than 1,700 volumes, including 300 international books in their native languages, from countries such as Sweden, the USSR, Turkey, and Denmark.[12][13] Interestingly, the books in the Children’s World had their own unique classifications based on emotional impact and were assigned a color group to evoke that feeling. Examples of classification groups included “books are fun” (picture books, adventure), “they make me feel at home in the world” (family stories, life in other countries), and “they tell me things I want to know” (science, history).[14] This classification was developed specifically for the exhibit but hinted at an expanding interest in creative classifications for the future. In contrast, the adult collection appeared to have no classification scheme, so librarians working in the second term decided to apply one using colored tape and loose subject categories, with moderate success.[15]

The Fair ended in October 1962 with the Space Needle as its most enduring memory. However, the Library 21 exhibit had a lasting impact. Over a million and a half people walked through the exhibit, learning about the future of library services, librarians, technology, and that they will always find a comfortable chair and a friendly “hello” in a library space. Over seventy librarians received special information retrieval training and a once-in-a-lifetime experience working at Library 21. And the books from the exhibit didn’t disappear forever – the ALA sold them at a discount to multiple libraries across the country: the reference collection went to Clatsop Community College in Astoria, Oregon; the adult collection went to G. David Schine; and the children’s collection was dispersed to a number of university and public libraries, including the Seattle Public Library.[16][17] Some of the children’s books were distributed by the United States Information Agency to foreign libraries. In 1964, a gift in honor of Charlemae Rollins of 2,000 volumes from the children’s collection was given to Roosevelt University by the ALA.[18] The library of the future lived on – in the books, memories, and lessons visitors and librarians brought away from the exhibit in 1962.

All sources are located in the ALA Archives, Library 21 Exhibit File, 1960-1965, Record Series 2/4/66, unless otherwise noted.

[1] American Library Association, “An automated Library of the Future designed by the American Library Association…,” news release, December 13, 1961, Box 6, Folder: News Releases, 1961-1964

[2] American Library Association, “An automated Library of the Future.”

[3] American Library Association, “The far-reaching and significant effects of Library 21…,” news release, April 16, 1963, Box 6, Folder: News Releases, 1961-1964

[4] American Library Association, “An automated Library of the Future.”

[5] Brigitte L. Kenney, “Library 21 at the Seattle World’s Fair,” Mississippi Library News, March 1963, pp. 5-8, Box 5, Folder: Reactions to Library 21

[6] American Library Association, “Library 21” (Chicago, 1962), Box 6, Folder: Library 21 Publications, 1962

[7] Margaret Gray, “Library 21,” Hawaii Library Association Journal, Fall 1962, pp. 9-13, Box 5, Folder: Reactions to Library 21

[8] Larry Johnson, “[More] on Library 21,” EdPress Newsletter, (August 20, 1962), 24:2, Box 5, Folder: Reactions to Library 21

[9] Louis Vagianos, “Librarians, librarianship, and library 21,” Wilson Library Bulletin, December 1962, pp. 331-4, Box 5, Folder: Reactions to Library 21

[10] American Library Association, “Library 21.”

[11] Alphonse F. Trezza to Roberta Anderson, August 14, 1962, Box 1, Folder: Disposition of ALA Book Collection

[12] Margaret Gray, “Library 21.”

[13] “Children’s Books from Other Countries included in the Children’s World in the ALA Library 21 exhibit at the Seattle World’s Fair April 21-October 21, 1962,” May 1, 1962, Box 1, Folder: Disposition of ALA Book Collection

[14] American Library Association, “A psychological approach to communication through books…,” news release, March 17, 1962, Box 6, Folder: News Releases, 1961-1964

[15] Sheila Stribley, “A Minnesotan at ‘Library 21,’” Minnesota Libraries, pp. 226-32, Box 5, Folder: Reactions to Library 21

[16] Alphonse F. Trezza to Roberta Anderson, June 21, 1963, Box 1, Folder: Disposition of ALA Book Collection

[17] Alphonse F. Trezza to G. David Schine, April 12, 1963, Box 1, Folder: Disposition of ALA Book Collection

[18] American Library Association, “A gift of 2,000 volumes of outstanding children’s literature…,” news release, March 1, 1964, Box 6, Folder: News Releases, 1961-1964