During World War I, most ALA operated libraries were stationed in US based military camps. However, a small number of librarians were sent overseas to help distribute books and run libraries. Harry Clemons was one such librarian.

In November 1918, M. L. Raney, director of the Library War Service’s overseas service, sent a cable message to Professor Harry Clemons with a simple question, “Will you accept appointment [of] official representative [of the] American Library Association … to develop library service for American forces in Russia? Books being shipped steadily.”

Clemons replied, “Will attempt library service starting when you direct.”

Harry Clemons was a professor of English and a librarian at the University of Nanking. Based in China since 1913, he was described by friends as a man who “has done an appalling amount of work.” His work ethic, and quite possibly his proximity to Siberia, made him an ideal fit for the challenging position.

Despite the location, the challenges faced by Clemons were not so different from other librarians during the war. The lack of help, the disorganization, endless sorting and arranging, and missing books, were common themes between Clemons and his stateside colleagues. He also seemed to enjoy the work. In December 1918, he wrote:

During the past week I have put the finishing touches to the arrangement of my prize collection of periodicals, and have sent out twenty mail sacks and fifty other parcels of this machine gun literature. More than half of the contents are now in the hands of the soldiers. The expressions of appreciation are not few … It has been a very grimy job, and I have looked upon so many magazine-cover ladies that completely clothed women of intelligent mien are at a premium with me. But I repeat that I am heartily glad that I found this work.

In another letter, Clemons wrote to his wife detailing the odyssey he undertook to retrieve a small box of books from a Russian customs office, a challenge unique to his location. The task took several days which involved no fewer than eleven Russian officials, repetitive questions about the recipient of the box, a letter of introduction from the camp’s Quartermaster, language barriers, and, most importantly, bribes. After finally receiving the box, Clemons concludes: “How I … lumbered in that broken down vehicle back towards the base and the driver struck three times for higher fare and how I finally paid him ten rubles and how we reach the warehouse and how two enlisted friends of mine carries the box up to the library without letting me help are other stories.”

Clemons’ hardships and his ability to overcome them did not go unnoticed, causing ALA Secretary Carl Milam to press Clemons to extend his stay, wanting Clemons to remain at his post for as long as possible.

Part of the reason why ALA wanted Clemon to stay was to make sure that ALA’s identity continued to be linked with the library. ALA praised Clemons for not establishing his office in the YMCA building as offered by the other organization, noting that, “The ALA must stand on its own feet, though it claims the reputation of being the best cooperator in the whole bunch of war service organizations.” They urged Clemons not to leave the library in the hands of the YMCA in the case that he did leave Siberia. During a time when ALA was a little-known organization, it was eager to assert its identity and not wanting it to be confused with a better-known organization.

After five months on the job, Clemons returned to the University of Nanking and appointed a chaplain, not a member of the YMCA, as his replacement.

Sources:

Harry Clemons Correspondence, War Service Correspondence, Record Series 89/1/5, Box 7, Volume 36, American Library Association Archives, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

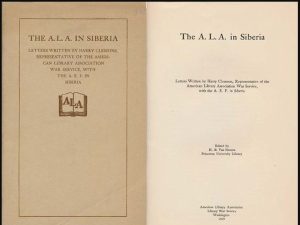

The A. L. A. in Siberia: Letters Written by Harry Clemons, Representative of the American Library Association War Service, with the A. E. F., ed. H. B. Van Hoesen (Washington: American Library Association, 1919): https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015033891345.

Blog post adapted from the presentation “The American Library Association Goes To War” by Cara Bertram, February 14, 2020.